1891 - The Morewood Massacre

Miners on the Edge

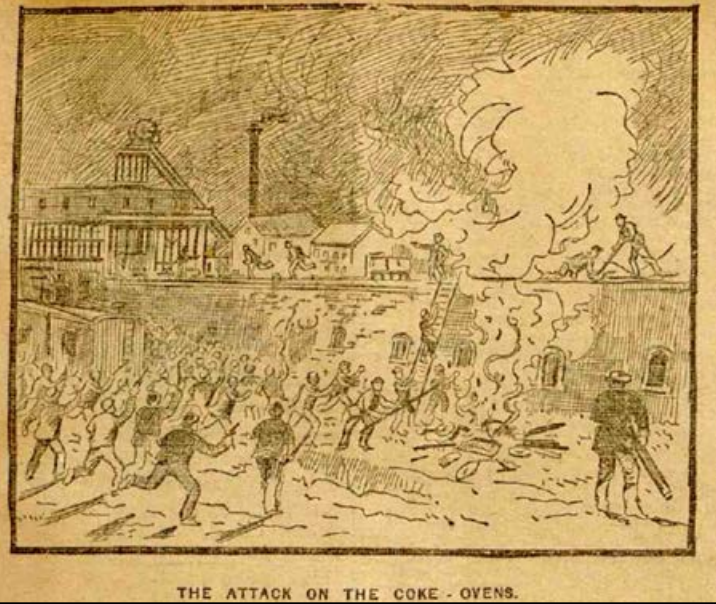

Before dawn on April 2, 1891, immigrant miners in Pennsylvania’s coke fields marched for bread and dignity. They were part of a larger strike movement sweeping the coke region, involving thousands of workers across multiple plants. What happened next became the Morewood Massacre, one bloody chapter in a national war between labor and capital.

The coke region of western Pennsylvania was a world built on fire, debt, and desperation. Rows of beehive ovens stretched for miles, each a stone dome glowing red through the night, casting a hellish glow visible for miles around. Coke is coal baked in those ovens until it becomes a hot-burning fuel for steelmaking. Men worked twelve to fourteen hours a day around the fires, choking on dust and smoke, their skin blistered from the heat. Burns and lung disease were constant companions.

Families lived in company-owned shacks with no sanitation. Pay came in scrip, a fake currency that only worked at the company store. It was a rigged casino where the boss always won, and the house took everything. Calling it 'free labor' was a sick joke - workers were chained to debt as tightly as if they wore shackles. Immigrant miners - Hungarians, Slovaks, Poles, Italians - were mocked as “Huns” and treated as disposable, but they built tight-knit communities with churches, taverns, and mutual aid societies. A wage cut in early 1891 was the last straw. The United Mine Workers called a strike, demanding fair wages and dignity. For once, workers stood together across ethnic lines. Leading them was John Fahy, a national United Mine Workers organizer, alongside local figures such as Peter Wisnosky. The union was still fragile, but these men risked everything to bring miners into the fight.

The Night of Blood

As the sun rose on April 2, 1891, a column of hungry men walked the road outside Morewood. They carried no guns - only banners and the hope their voices might be heard. Sheriff William Clawson’s deputies and Henry Clay Frick’s company guards were waiting with loaded rifles. Clawson bore direct responsibility for deputizing the shooters, but Frick’s coke empire set the system that made such killings routine. Without warning, the guards fired into the crowd. Ten men were gunned down in cold blood, their bodies dumped in the mud like trash for daring to demand bread for their kids. Among the dead were Joseph Sticco and Michael Cheslak, recent immigrants whose families had crossed the ocean for survival, only to lose them to company gunfire. The youngest was barely out of his teens. Their widows and children were left destitute.

The names of the dead are drawn from reconstructed lists, since contemporary papers mangled spellings or ignored them outright, and no definitive roll was ever made. What is known: Joseph Steico, Michael Cheslak, Andrew Kollar, George Kutnak, John Pasterick, George Sabol, George Sekerak, Joseph Turchick, Martin Visnosky, and John Vovk. Most were Hungarian or Slovak immigrants who came chasing survival.

Contemporary papers smeared the slain men. The Pittsburgh Press called the strikers “an infuriated mob of Huns,” a racist slur meant to strip them of dignity. The New York Times labeled them “rioters” and excused the deputies. The press did its job - running cover for the bosses, painting men with lunch pails as if they were an invading army.

Aftermath and Silence

The massacre crushed the strike. The company refused concessions, and fear spread through the coke fields. Newspapers painted the dead as dangerous foreigners, glossing over the fact that they were simply men demanding bread for their children. Nationally, corporations tightened their grip while the federal government protected property over people. Morewood was one flashpoint in a broader war in the coalfields - the same pressures that would soon explode at Homestead in 1892 and in the anthracite strikes later in the decade. The union effort collapsed here, but the memory of Morewood haunted every miner who picked up a shovel or walked a picket line in the years to come.

Legacy

The Morewood Massacre showed the brutality of industrial America: how capital answered labor’s pleas with bullets, and how immigrant lives were treated as expendable. It also revealed the power of solidarity, even if short-lived. Frick faced no consequences for Morewood. Instead, he doubled down, and within a year he ordered Pinkertons into Homestead, where even more workers would die. Violence wasn’t the exception in his empire - it was the business model.

America quickly forgot the men of Morewood, their names lost or mangled in hostile newspapers. But their blood didn’t just vanish into the dirt - it’s baked into the steel that built America, a reminder that every ton carried the price of their lives.

Sources

- The Pittsburgh Press, April 3, 1891 - contemporary coverage, called the miners an “infuriated mob of Huns.”

- The New York Times, April 4, 1891 - described the marchers as “rioters,” justifying the deputies.

- Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Vol. 2 (1947) - detailed context on the Morewood strike and its role in the labor wars of the 1890s; includes discussion of victim lists from reconstructed sources.

- David P. Demarest, The River Ran Red: Homestead 1892 (1992) - situates Morewood as a precursor to Homestead.

- James P. Cannon, “The Morewood Massacre,” The Militant (1941) - a labor history retelling, widely cited in union circles.

- Robert Bruno, “Labor’s Bloody Past: The Morewood Massacre of 1891,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies (1991) - academic analysis of the strike and killings, including detail on the uncertainties around the victim roll.

#RiotADay #LaborHistory #USHistory #History 🗃️