America’s First National Strike: The Great Railroad Strike of 1877

Sparks on the Tracks

On July 16, 1877, engineer Charles Peck reported for duty in Martinsburg, West Virginia. He had already seen his wages cut three times in four years. When the Baltimore and Ohio announced yet another 10 percent cut, Peck refused to take out his train. He uncoupled the engine, stood by the roundhouse, and told reporters, “We cannot live on what they pay us.” His defiance set the tone: no trains would leave until wages were restored. Local police failed to move them, the governor called out the militia, and when that did not work federal troops were dispatched.

A Nation Brought to a Halt

By July 17, the strike spread to Baltimore. Within days it jumped west to Pittsburgh, Chicago, and St. Louis. Rail yards across the nation were swarmed. At its peak more than 100,000 workers took part, and more than half of the nation’s freight traffic stood still. The United States had seen strikes in single towns or factories before, but never anything like this. The summer of 1877 revealed the terrifying and electrifying power of a national strike. It was a true nationwide strike that linked city to city and worker to worker. Suddenly railroad barons, governors, and even the President faced not a dispute in one place but a rebellion spanning the nation.

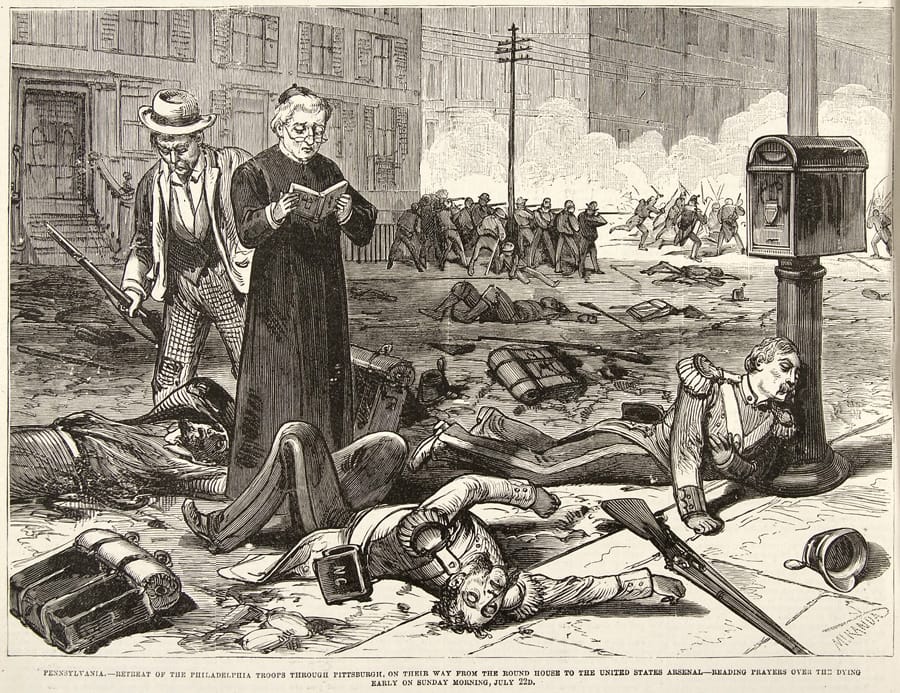

Fire and Gunfire

On July 19 in Baltimore, militia fired into crowds, killing at least ten. By July 21, Pittsburgh was in flames. Guardsmen from Philadelphia shot into a crowd at the 28th Street crossing. The Pittsburgh Daily Post reported, “The militia fired into the crowd and thirty or forty people fell, killed and wounded.” Eyewitnesses told Harper’s Weekly, “The dead lay where they fell. Women and children shrieked and fled in every direction.” By dawn on July 22, rail property burned across the city: 39 buildings, 104 locomotives, 46 passenger cars, and more than 1,200 freight cars destroyed. Newspapers branded the upheaval an insurrection and warned of another Paris Commune. Translation: the bosses were scared shitless that working people might decide whether trains moved, that the men and women who actually built and ran the country might realize they had the power to shut it down.

People in the Streets

The strike was never just the men on the tracks. Wives hauled food to the lines. Children carried messages. Black and white laborers stood together in many places, even as racism and mistrust lingered. In St. Louis by the end of July, the Workingmen’s Party organized a general strike that briefly ran the city’s daily life. For elites, that looked like revolution.

The Cost of Defiance

Nationwide, roughly 100 people were killed and many hundreds wounded. In Pittsburgh, dozens fell in a single night. In Baltimore, ten to twenty-two died over several days. In Reading, Pennsylvania, at least ten were shot dead when militia fired into a crowd. In Chicago, estimates ranged from fourteen to thirty killed before order was restored. Thousands were arrested, and many workers were blacklisted. Men like Charles Peck, who had dared to stand at the roundhouse in Martinsburg, likely found their names passed around on do-not-hire lists, their brief moment in history followed by years of quiet hardship. Their families bore the weight too. Wives who once carried food to the lines now struggled to feed children with no wages coming in. Some drifted into reform groups and later labor auxiliaries, carrying the strike’s memory forward. Children who had run messages between pickets often ended up in the mills and rail yards themselves, pressed into work to make up for lost income. The cost of defiance lingered long after the gunfire faded.

The First National Strike

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877 was the largest labor uprising in U.S. history up to that point, and the first to knit together towns and cities into a truly national revolt. It erupted during the Long Depression that followed the Panic of 1873. Unemployment soared, wages collapsed, and resentment simmered in a nation still scarred by the Civil War and Reconstruction. Radical ideas from Europe such as socialism, anarchism, and memories of the Paris Commune haunted politicians and editors. To business leaders and politicians, the strike looked like class war. To workers, it was survival. And unlike the astroturfed spectacles of our own day, this was no manufactured "Truckers for Trump" roadshow. It was a real movement, with real sacrifice written in blood and hunger.

The strikers did not win back their pay, and many lost their jobs. But the shock waves were lasting. States built new armories in industrial cities and strengthened the National Guard. Railroad executives learned to coordinate with governors and the White House. Workers learned something too: they were not powerless. The summer of 1877 helped spark the rapid growth of national labor organizations, from the Knights of Labor to the unions that followed. It set a precedent for coordinated action that would echo through the Pullman Boycott of 1894 and beyond.

The Story We Carry

The Great Railroad Strike was not only about wages. It was about dignity in an age when corporations treated workers like track ballast. The bad guys wore uniforms or sat in boardrooms, ordering rifles turned on hungry families. The good guys were not just the strikers, but the women, children, and neighbors who stood with them. Whenever you hear talk of “essential workers,” remember the people who laid their bodies across the tracks in 1877. They showed that America runs on labor, and that when labor stops, everything stops. That is the truth the bosses feared then, and still fear today.

Sources

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Great Railroad Strike of 1877.”

- Library of Congress, “This Month in Business History: The Great Railroad Strike of 1877.”

- Digital History, University of Houston, “The Great Railroad Strike of 1877.”

- Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, “Railroad Strike of 1877.”

- University of Nebraska–Lincoln, Railroads and the Making of Modern America: Rutherford B. Hayes diary excerpts on the 1877 strike.

- Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History, “Great Railroad Strike of 1877.”

- ExplorePAHistory historical marker text on the Pittsburgh shootings and destruction figures.

- Chicago History sources on the 1877 “Battle of the Viaduct” casualty estimates.