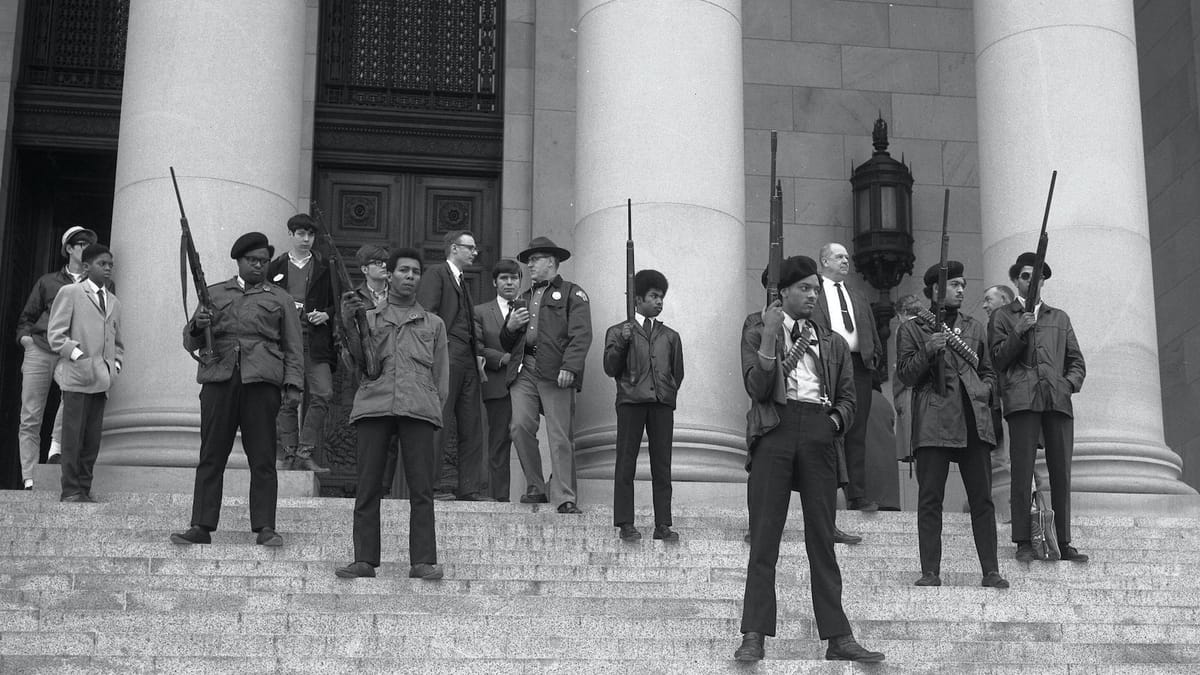

Black Panthers at the State Capitol, 1967

Conservative gun control has always had one target: Black people with guns. After the Civil War, Southern conservatives passed laws to disarm freed slaves. During Jim Crow, they banned cheap handguns that Black people could afford. And in 1967, when thirty armed Black Panthers walked into the California State Capitol exercising their Second Amendment rights, Ronald Reagan and the NRA passed gun control legislation in less than three months.

Then, once the Black Panthers were destroyed, those same conservatives became Second Amendment absolutists and pretended they'd always opposed gun restrictions.

The story of May 2, 1967 exposes the lie.

The Setup

Oakland, California, 1966. Police brutality against Black residents wasn't occasional, it was policy. Cops stopped, searched, beat, and arrested Black people without cause or consequence.

Huey Newton was a law student at Oakland City College who had studied California's gun laws obsessively. Bobby Seale was an organizer who understood political theater. Together in October 1966, they founded the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense with a strategy that was equal parts constitutional law and street-level resistance: watch the cops. Armed. With law books.

Newton knew exactly what was legal. Open carry of loaded firearms was permitted. Entering government buildings with weapons was permitted. Observing police activity was permitted as long as you kept your distance. The Panthers would show up at arrests with shotguns in one hand and statute books in the other, reading constitutional rights to suspects from the legal distance, citing chapter and verse when police objected.

They called it "copwatching." Within months, armed Black Panthers were conducting regular patrols through Oakland's Black neighborhoods. When cops pulled someone over, Panthers rolled up with loaded rifles and pistols, stood at the legal distance, and observed. If officers violated someone's rights, the Panthers cited the law and threatened lawsuits.

In February 1967, the Panthers provided armed escort for Betty Shabazz, Malcolm X's widow, at the San Francisco airport. The images went national. By spring, the Party had gained enough visibility that politicians noticed. And panicked.

The Politician

Don Mulford was a Republican assemblyman from Oakland. The Oakland Police Department had been pressuring Sacramento for months, demanding legislation to stop the copwatching. Mulford became their instrument.

In April 1967, he called into a radio show where Huey Newton was being interviewed. Newton later recounted that Mulford told him directly: he planned to introduce a bill that would "get" the Black Panthers. Not reduce crime. Not improve safety. Get the Black Panthers specifically.

Mulford drafted Assembly Bill 1591 to ban public carrying of loaded firearms. The bill was crafted, in his own words with help from the National Rifle Association, to stop what the Panthers were doing. Never mind that what the Panthers were doing was completely legal. Armed Black people exercising constitutional rights was a threat that had to be eliminated.

Mulford publicly claimed the bill had "nothing to do with any racial incident." Willie Brown, a Black Democratic assemblyman who would later become mayor of San Francisco, called him out. Brown noted that Mulford had been a gun rights supporter until Black people started carrying. Then suddenly, open carry became an urgent public safety crisis.

The bill moved through committee with bipartisan support. Democrats and Republicans lined up to disarm the Panthers. And the NRA, the organization that would later claim any gun restriction violated sacred constitutional rights, helped write the legislation.

The March

On May 2, 1967, thirty Black Panthers drove to Sacramento to protest the Mulford Act. Twenty-four men and six women, armed with .357 Magnums, 12-gauge shotguns, and .45-caliber pistols. Every weapon loaded. Every weapon legal. They wore their signature black leather jackets and berets. They had alerted the press. They had a prepared statement.

What they did was completely legal under California law. They kept their guns pointed at the ceiling. They didn't brandish. They didn't threaten anyone. They violated no statute.

By coincidence, Governor Ronald Reagan was on the lawn that day hosting a picnic for eighth-graders. The timing gave him perfect optics: armed Black militants arriving while schoolchildren watched. Reagan was quickly ushered inside.

Bobby Seale stood on the Capitol steps and read "Executive Mandate Number One" to the crowd and cameras. The statement explicitly called out the Mulford Act as unconstitutional, racist legislation designed to keep "the Black people disarmed and powerless" in violation of both the Second and Fourteenth Amendments.

Then the Panthers walked through the front doors. Into the building. Through the hallways, heading toward the Assembly chamber. What happened next depends on who you ask. Some accounts say they were stopped before entering. Others say several Panthers made it inside the chamber mid-session, causing some legislators to dive under their desks. News footage shows Panthers in the corridors with their weapons pointed at the ceiling, surrounded by cameras. State police intervened, not because the Panthers had broken any law, but because the spectacle was too much.

Police arrested Bobby Seale and five others. The charges? Not weapons violations. Those were legal. They were charged with disrupting a legislative session. Misdemeanors. They pleaded guilty and paid fines.

But the images went worldwide. Black people with guns, in the seat of government, demanding their rights. The Black Panther Party, which had fewer than 100 members before May 2, exploded in visibility and membership overnight.

They had also given their enemies everything they needed.

The Response

The Mulford Act, which had been moving slowly through the legislature, suddenly became an "urgency statute" - a designation requiring a two-thirds supermajority but allowing immediate implementation. Mulford revised the bill to make it even more restrictive, adding a provision making it a felony to bring loaded weapons into the Capitol. The bill passed the Assembly 70-5. It passed the Senate 29-7. Overwhelming bipartisan support.

On July 28, 1967, less than three months after the Panthers marched, Governor Ronald Reagan signed the Mulford Act into law.

Reagan stood before cameras and said he saw "no reason why on the street today a citizen should be carrying loaded weapons." Guns, he said, were "a ridiculous way to solve problems that have to be solved among people of good will." He assured the public that the Mulford Act "would work no hardship on the honest citizen."

This was the same Ronald Reagan who would later become the face of conservative gun rights. The same Reagan who told the NRA in 1983 that you don't get gun control by "disarming law-abiding citizens." The same Reagan who would be endorsed by the NRA in 1980, their first presidential endorsement ever.

But in 1967, when Black people were the ones carrying guns, Reagan couldn't sign gun control fast enough.

The National Rifle Association supported the Mulford Act. The organization that had opposed federal gun registries helped draft legislation to ban open carry in California. Franklin Orth, the NRA's executive vice president, testified that the organization had worked with Mulford to craft the bill "to protect our constitutional right to bear arms and yet to assist the law enforcement people."

The NRA had supported gun control before - the 1934 National Firearms Act, the 1938 Federal Firearms Act, parts of the Gun Control Act of 1968. Throughout most of its history, the NRA was a sportsmen's organization that occasionally lobbied on gun issues, not a Second Amendment absolutist group.

But the Mulford Act was different. This wasn't about regulating machine guns or criminal access to firearms. This was about disarming a specific political group because white people were frightened of armed Black men. And the NRA was fine with it.

In 1977, hardliners staged a coup at the NRA's annual convention in Cincinnati. They ousted the old guard and transformed the organization into a political powerhouse that opposed virtually all gun regulations. The new leadership argued that any gun control was a slippery slope to confiscation.

It was the exact argument the Black Panthers had made in 1967. A decade later, the NRA adopted that framework wholesale and applied it to white gun owners. They conveniently forgot they had supported the Mulford Act.

The Aftermath

The Mulford Act didn't reduce crime. Studies showed it had virtually no effect on California's crime rates. What it did was make the Panthers' copwatching patrols illegal. Mission accomplished.

The Panthers shifted tactics. They launched community programs: free breakfast for children, health clinics, education initiatives, sickle cell anemia testing. The free breakfast program alone fed tens of thousands of kids and became the model for federal school breakfast programs.

But the government wasn't interested in feeding children or providing healthcare. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover called the Black Panthers "the greatest threat to the internal security of the country." Not the Ku Klux Klan. Not white supremacist bombers. The Black Panthers. Armed Black people monitoring police and feeding children was more terrifying to the state than white terrorism.

Hoover directed COINTELPRO to neutralize them. The FBI infiltrated the organization, created conflicts between members, and coordinated with police to raid Panther offices and murder Panther leaders. Fred Hampton, chairman of the Illinois chapter, was drugged by an FBI informant and then shot to death in his bed by Chicago police in 1969. He was twenty-one years old. The police fired over ninety rounds into the apartment. The Panthers fired one.

By 1982, the Black Panther Party was effectively defunct, dismantled by police raids, internal conflicts, and federal sabotage. The Mulford Act had served its purpose.

California's gun laws grew stricter over the decades. The state now has some of the most comprehensive gun regulations in the country. Conservative commentators love to point out that California still has gun violence despite strict laws. What they don't mention is that California has a gun death rate of 7 per 100,000 people, while states with minimal gun control like Mississippi and Louisiana have rates above 25 per 100,000.

The Mulford Act established California's approach to gun regulation. But more importantly, it revealed what gun rights have always meant in America: rights for white people. When Black people tried to exercise the same rights, the law changed overnight.

The Story We Carry

The Black Panthers' march to Sacramento was brilliant political theater and devastating constitutional argument rolled into one. They proved exactly what they set out to prove: that gun rights only mattered when white people exercised them. They forced the mask off. And they paid for it with a law designed to disarm them and a decades-long campaign by the FBI to destroy them.

Ronald Reagan and the NRA didn't fear guns. They feared Black people with guns. They feared Black political power, Black resistance, Black refusal to submit to police violence. So they changed the law. And later, when it suited them, they reversed course and claimed gun rights were sacred. Because by then, gun ownership had been safely re-whitened.

The Panthers knew how it would play out. Huey Newton understood that the system would respond by changing the rules the moment Black people used them. They marched anyway. They read their statement on the Capitol steps. They walked through those doors with their heads up and their weapons legal.

And America proved them right.

Sources

- Adam Winkler, Gunfight: The Battle Over the Right to Bear Arms in America (W.W. Norton, 2011)

- Bobby Seale, Seize the Time: The Story of the Black Panther Party and Huey P. Newton (Black Classic Press, 1991)

- Huey P. Newton, Revolutionary Suicide (Penguin Books, 1973)

- Mulford Act, California Assembly Bill 1591 (1967)

- Harvard Journal on Legislation, "Scattershot: Guns, Gun Control, and American Politics"

- Duke Center for Firearms Law, "The Black Panthers, NRA, Ronald Reagan, Armed Extremists, and the Second Amendment"

- KCRA-TV news footage, Black Panther protest at California State Capitol (May 2, 1967)

- Contemporary coverage: Sacramento Bee, Los Angeles Times, Associated Press (May-July 1967)