Clubs in the Park: Tompkins Square, 1874

Hunger and Hope

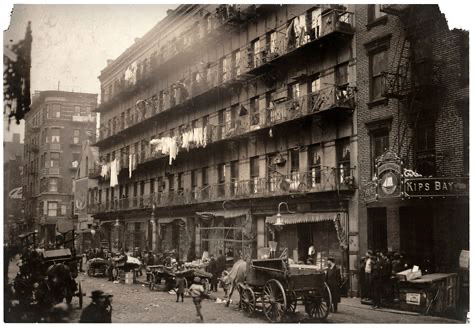

In the winter of 1874, New York City’s poor were starving. The Panic of 1873 had gutted the economy. Factories shut down, banks collapsed, and the city’s elites shrugged while families froze. So the unemployed did the unthinkable: they gathered in public and demanded bread instead of silence.

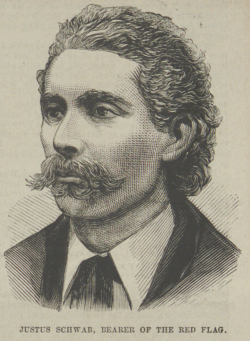

Among them was Justus H. Schwab, a German immigrant, anarchist, and saloonkeeper whose East First Street tavern - known simply as Schwab’s - had become a refuge for workers, immigrants, and the unemployed. Hostile newspapers called it “the most notorious radical resort in the city.” The place itself was tiny - eight feet wide, thirty feet deep. A cramped bier-höhle (beer cave). Still, it felt like a smoky parliament. Inside, German anarchists, socialists, and labor organizers argued about freedom over cheap beer. Even writers like Walt Whitman and Ambrose Bierce passed through.

There was Samuel Gompers, a young cigar maker who would one day lead the American Federation of Labor. He stood shoulder to shoulder with men twice his age. There were mothers clutching children’s hands, immigrants shouting in German, Irish, and Yiddish, and laborers carrying signs that read simply: We Want Work.

They weren’t rioters. They were neighbors, families, workers, the poor. They gathered to demand the most basic human right: to live.

Clubs in the Square

Then the cops came. Mounted, armed, and eager. Chief James J. Kelso sent nearly 1,600 officers and cavalry charging into a crowd of 5,000 to 10,000. They didn’t just clear the square, they beat the hell out of it. Clubs smashed skulls. Horses trampled bodies. Men, women, kids... it didn’t matter. The New York Herald called it “a carnival of blood.” That’s one way to describe state-sanctioned assault.

Samuel Gompers barely survived. He later recalled that the police “attacked men, women, and children without discrimination.” He only saved himself, he said, by diving headfirst into a cellarway.

Schwab was arrested and dragged off for daring to stand with the unemployed. At least 40 others were hauled off with him.

Spin and Contempt

Mayor William Havemeyer praised the police for restoring “order.” Elite newspapers sneered that the unemployed were “communists” and “idlers.” And from his comfortable pulpit, preacher Henry Ward Beecher offered this gem: if the poor didn’t like starving in New York, they should just move west. Easy fix, right? Pack up your starving kids and walk miles into nowhere. The compassion of America’s ruling class, ladies and gentlemen.

It is a familiar playbook. Label protesters as dangerous, dismiss their demands as illegitimate, mock their suffering, and then justify the crackdown as “order.” The words change but the contempt doesn’t. From striking miners called anarchists in the 1890s, to civil rights marchers branded agitators in the 1960s, to Black Lives Matter protesters called thugs in the 2020s, the tactic is the same. Dehumanize the people, praise the police, bury the truth.

Aftermath and Memory

The Tompkins Square Riot was not chaos. It was a message. Ask for bread, get the club. Ask for work, get trampled by horses. Ask for dignity, get locked in a cell.

Schwab’s tavern would outlive the riot. The park may have been beaten down, but in Schwab’s saloon the rebellion carried on. Workers, immigrants, and the unemployed crammed into the bar. Beer sloshed onto the counter. Arguments shook the walls. Marx’s Capital, fresh in German, passed hand to hand, sticky with beer, as they argued about wages and freedom. It was more than a saloon. It was a sanctuary and a parliament for the dispossessed. The saloon itself is long gone, replaced by a co-op built in 1910, but its spirit survives in memory. City officials banned further demonstrations in Tompkins Square, trying to erase the memory of what happened with ordinances and paperwork as much as with clubs.

Tompkins Square itself would host rebellion again: labor rallies in the 1880s, anarchists in the 1980s, homeless tent cities and punk shows in the 1990s. The park remembers, even if the city pretends not to.

The Lesson

Whenever the poor demand relief, the powerful call them a mob. Whenever workers demand dignity, the state answers with violence. Tompkins Square was a rehearsal for Haymarket, for Ludlow, for every baton charge against striking workers or protesting students since. It revealed something deeper about America. Again and again, those willing to change society for the better are the ones the state chooses to club, trample, or kill.

The cops called it a riot. Of course they did. History should call it what it was: poor people demanding to live, and the state answering with hooves and clubs. This is America’s habit... to beat down anyone with the audacity to demand a better world, then bury the evidence under words like “order” and “riot.”

Sources

- New York Herald, January 14, 1874 (contemporary coverage calling it “a carnival of blood” and reporting on casualties and arrests).

- New York Times, January 14, 1874 (coverage praising police actions, citing deployment of nearly 1,600 officers).

- Samuel Gompers, Seventy Years of Life and Labor (1925), memoir describing his escape).

- Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Vol. 1 (International Publishers, 1947).

- Henry David, The History of the Haymarket Affair (Farrar & Rinehart, 1936), background on Schwab and the anarchist movement.

- Timothy Gilfoyle, A Pickpocket’s Tale: The Underworld of Nineteenth-Century New York (W.W. Norton, 2006).

- Tyler Anbinder, Five Points (Free Press, 2001).

- Bruce C. Nelson, Beyond the Martyrs: A Social History of Chicago’s Anarchists, 1870–1900 (Rutgers University Press, 1988).

- Henry Ward Beecher, quoted in contemporary accounts, mocking unemployed workers to “emigrate west.”

- Paul Avrich, An American Anarchist: The Life of Voltairine de Cleyre (Princeton University Press, 1978) – context on anarchist networks linked to Schwab.