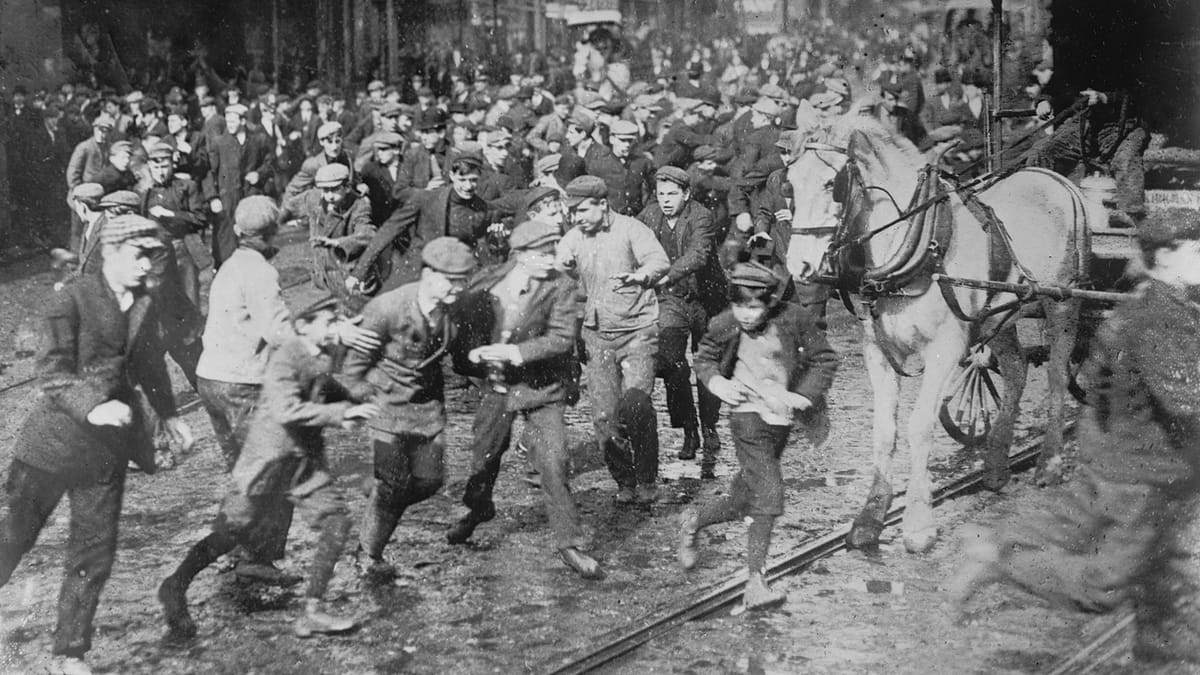

Everett Massacre, 1916

They called it Bloody Sunday. That's sanitized history for you - like the blood washed off the dock and into Port Gardner Bay on November 5, 1916, taking bodies with it. At least seven men died that day, maybe twelve. The exact number got lost in the water, buried in official silence, scattered across a century of convenient forgetting. What's certain is this: when 300 workers showed up to exercise their First Amendment rights, mill owners and their deputized goon squad met them with a firing squad.

Why 1916 Mattered

America was choosing sides. World War I raged in Europe. Preparedness parades marched through cities, business leaders beating the drums for intervention and profit. In San Francisco that July, someone had planted a bomb at the Preparedness Day parade - ten dead, forty wounded. Two labor organizers, Thomas Mooney and Warren Billings, got framed for it and sentenced to death on perjured testimony. The bombing gave bosses everywhere an excuse to paint all labor radicals as terrorists.

Two years earlier, the Colorado National Guard had massacred striking miners and their families at Ludlow - women and children burned alive in their tents, twenty-five dead including eleven kids. John D. Rockefeller's company had orchestrated it. The Commission on Industrial Relations had spent months documenting the brutality, and its 1915 report condemned the violence and called for an eight-hour day, but nothing changed. The lesson was clear: capital would murder to keep control.

And everywhere, workers were organizing. The IWW - the Wobblies - was at its peak, maybe 60,000 members strong, organizing across craft lines, across races, bringing unskilled workers into the same union with the skilled, building One Big Union. They'd won strikes in textiles, mines, lumber camps from Minnesota to Montana to the Pacific Northwest. The summer of 1916 saw strikes erupting across the timber industry - thousands walking out demanding the eight-hour day, better camps, real wages. Railroad workers had just threatened a nationwide strike and forced Congress to pass the Adamson Act, granting them ten hours' pay for eight hours' work.

In Everett, Washington, all these currents converged on a dock in November. The timber barons saw their world under siege. The Wobblies represented everything they feared: solidarity that crossed every line capital had drawn to keep workers divided. And so the Commercial Club decided to draw a line in blood.

The Work That Ate Fingers

You could spot a shingle weaver by his hands. Not all of them, mind you - just the ones who'd been at it long enough. Missing fingers were the tell. A badge of survival in an industry that treated human bodies as expendable as sawdust.

The work was simple, brutal physics. You stood at a screaming circular saw, feeding raw cedar blocks into spinning steel teeth 50 times a minute, every minute, hour after hour. Your hands danced inches from blades that didn't care whether they bit wood or flesh. The saw set the pace. You kept up or you bled. Most men bled anyway - it was just a question of how much and how often. The cedar dust filled your lungs until you couldn't breathe right anymore, a disease they called "cedar asthma" that buried men before their time.

In 1916, shingle weavers in Everett, Washington were making less than they had in 1914. Mill owners had slashed wages during the recession, promising to restore them when cedar prices recovered. The prices came back. The wages didn't. In May, the workers struck.

Wobblies and the Dream of One Big Union

The Industrial Workers of the World - Wobblies - weren't originally involved. The shingle weavers belonged to an AFL craft union, the skilled trades workers who looked down on the IWW's radical vision of one big union for everyone: skilled, unskilled, Black, white, immigrant, native-born. But when the strike dragged on and mill owners doubled down, the Wobblies showed up anyway.

The IWW had been tearing through the Northwest lumber industry all year. In Minnesota that winter, lumber workers had struck and won wage increases. Across Washington, Idaho, and Montana, Wobblies were organizing camp by camp, signing up thousands. Their strategy worked because it was simple: flood a town with speakers, pack the jails, clog the courts, exercise constitutional rights until the machinery broke down. Free speech fights, they called them. They'd won before in Spokane, Fresno, and a dozen other mill towns where bosses thought the law was whatever kept workers quiet.

The Commercial Club - the polite name for Everett's cabal of timber barons who owned the mills, the land, the cops, and the politicians - saw the IWW as an existential threat. Sheriff Donald McRae, once a union man himself who'd served as secretary of the shingle weavers union, had become their enforcer. He started arresting IWW speakers in July. When arrests didn't work, he graduated to beatings.

Beverly Park

The worst came on October 30, 1916. Forty-one Wobblies arrived by ferry that evening to speak at Hewitt and Wetmore, Everett's traditional free-speech corner. More than 200 armed men calling themselves "citizen deputies" met them at the dock. They beat some of them right there. Then they loaded the rest into trucks and drove them to Beverly Park, a wooded area southeast of town.

In the darkness and cold rain, McRae's deputies formed two lines - a gauntlet. They made the Wobblies run it one by one. Clubs, guns, rubber hoses loaded with lead shot. A family living nearby heard the screams and came to watch deputized citizens of Everett beating unarmed men until they couldn't stand. When it was over, the bloodied Wobblies were left to walk or crawl the 25 miles back to Seattle.

The next morning, even through the rain, investigators found the ground at Beverly Park still soaked with blood.

The Dock

November 5 was a Sunday. About 300 Wobblies boarded two steamers in Seattle - the Verona and the Calista - and headed north. They were coming back to Everett in numbers, to show the mill owners that you can't beat solidarity into submission. They sang "Hold the Fort" as they approached the dock.

The Commercial Club knew they were coming. McRae and his 200-plus armed vigilantes waited on the pier and on tugboats in the harbor. Rumors had spread that anarchists were coming to burn the town. The kind of lie that makes massacre feel like self-defense.

When the Verona pulled up, Sheriff McRae shouted: "Who are your leaders?"

Every man on board answered: "We all are!"

Then someone fired. Nobody knows who pulled the first trigger, and it doesn't matter. Ten minutes of hell followed. The vigilantes opened fire from three sides - the dock, the shore, even from a tugboat that had flanked the Verona. The Wobblies, mostly unarmed, stampeded to the far side of the ship, nearly capsizing it. Men fell into the water. Some drowned. Some were shot while they drowned.

On the deck of the Verona lay Hugo Gerlot, 23. Abraham Rebenovitz, 30. Gustav Johnson, 24. John Looney, 27. Felix Baran, 24, dying. At least seven more disappeared into the bay, their bodies never recovered or quietly disposed of later.

On the dock, two deputies lay dead: Jefferson Beard and Charles Curtis. They'd been shot in the back by their own side - "friendly fire" from panicked businessmen playing soldier, shooting wildly through wooden walls and into the chaos they'd created. Sheriff McRae took two bullets in the leg. Twenty others were wounded.

The Verona's captain hid behind a safe under a mattress. An IWW member named James Billings forced the engineer at gunpoint to reverse the engines and get them the hell out of there. They limped back to Seattle, passing the Calista and warning them to turn around.

Justice for Sale

When the boats returned to Seattle, 74 Wobblies were arrested and charged with murder. Teamster Thomas Tracy went to trial first. His lawyers - including the legendary George Vanderveer, "Counsel for the Damned" - dismantled the prosecution's case. The state relied on perjured testimony and hearsay. Autopsies proved that both deputies died from bullets fired by their own side, not from Wobblies who mostly didn't have guns.

On May 5, 1917, a jury that included women - rare for the time - acquitted Tracy. The other 73 prisoners were released. Not one vigilante, not one deputy, not Sheriff McRae, not a single member of the Commercial Club faced charges.

Governor Ernest Lister sent the National Guard to occupy Everett and Seattle. The shingle weavers' strike collapsed three days after the massacre. They went back to work with no gains, no concessions, nothing. The mill owners won. The law stood with the men who pulled the triggers.

What They Carried Away

The IWW buried three of their dead - Baran, Gerlot, and Looney - in a public funeral in Seattle that drew 1,500 people. They marched through downtown in rows of four, red roses pinned to their chests, singing the Red Flag. Rebenovitz and Johnson were sent home to their families. The others who died stayed lost.

There are photos of the survivors, mugshots taken when Seattle police booked them. Faces of men who'd come within inches of dying for the right to speak. Most were in their twenties. The youngest, Axel Downey, was 17. They came from 24 states and eight countries. They were laborers, longshoremen, loggers, cooks, miners, blacksmiths. Itinerants, drifters, men whose lives were spent moving from job to job, surviving by solidarity.

Sheriff McRae disappeared after the massacre. Reviled by labor, despised even by the businessmen who'd used him, he went into seclusion. His family doesn't know when he died.

No monument marked the massacre for a hundred years. In 2016, the IWW placed a wreath at the site and marched up Hewitt Avenue to the corner where their fellow workers had wanted to speak. They did it without a permit, just like in 1916.

The mill owners got what they wanted: broken strikes, cheap labor, no accountability. The Wobblies got what they always got: martyrs, songs, and the long memory of those who refuse to forget.

The bodies in the bay carried away the proof. The state carried away the lesson. If you're poor enough, if you're radical enough, if you demand too much, America will kill you and call it law and order. And then it will forget your name.

Sources

- Norman H. Clark, Mill Town: A Social History of Everett, Washington (1970)

- Walker C. Smith, The Everett Massacre: A History of the Class Struggle in the Lumber Industry (1917)

- HistoryLink.org, "Everett Massacre (1916)"

- University of Washington Libraries, IWW History Project and Everett Massacre Collection

- Everett Public Library, Everett Massacre Collection