Labor Day Isn’t a Picnic. It’s a Warning.

It wasn’t just blood on the streets. It was collective action. It was sacrifice. It was working people deciding they would not live quietly under the boot anymore. Like most of these incidents, they called it a riot. It was a strike. A movement. It only became a riot when they tried to kill it.

The Model Town That Starved Its Workers

George Pullman built his company town south of Chicago like a cage dressed up as a gift. Neat rows of houses he owned. Stores he owned. A school and a church he owned. He called it paternalism. Workers called it something else: slavery with rent due.

In 1894, Pullman cut wages but kept rents the same. Families starved while the boss collected. “We struck at Pullman because we were without hope,” workers later told the American Railway Union. That single line, left out of textbooks, explains everything. Despair organized is power.

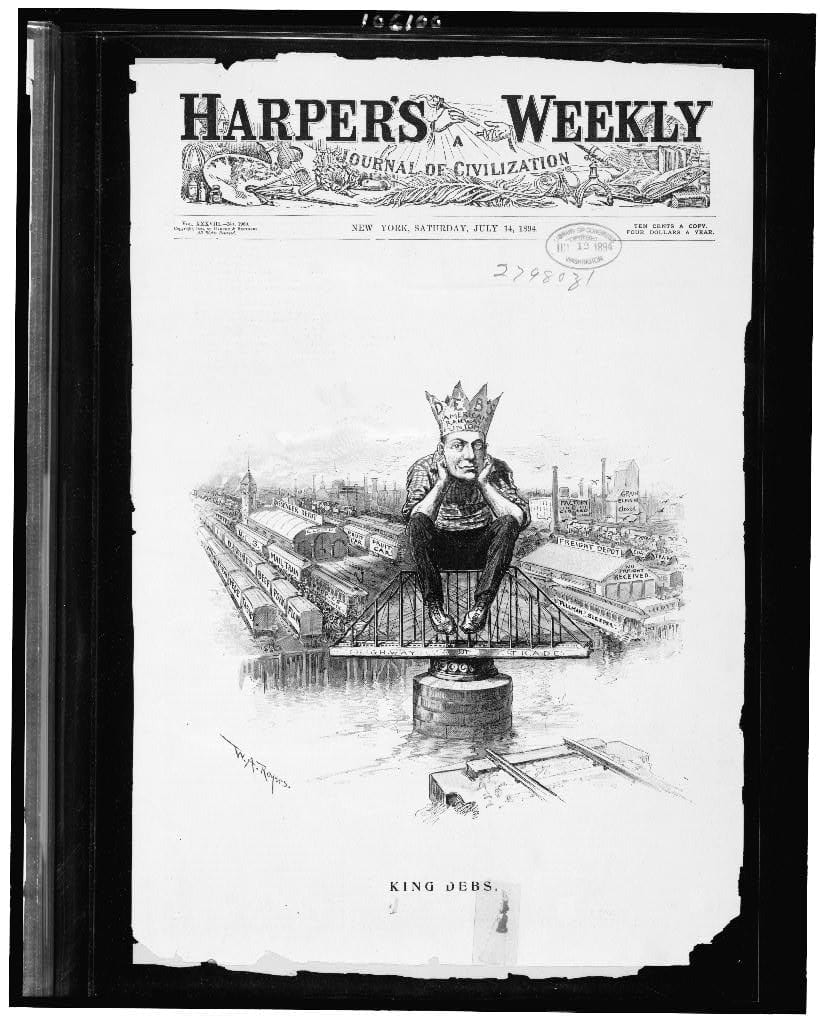

Enter Debs

Eugene Victor Debs was not some outside agitator. He had started on the railroad as a teenage grease monkey, scraping grime from engines. He knew the smell of sweat and the sound of iron. By 1894, he was President of the newly formed American Railway Union, the first industrial union in U.S. history, open to every kind of rail worker, not just a craft elite.

Debs told workers the truth. Pullman was “a rich plunderer” and “an oppressor of labor.” He warned them that Pullman’s much-advertised paternalism was slavery in a suit. “You are striking to avert slavery and degradation,” he said. He didn’t flatter their hunger. He named their power.

The Boycott That Froze a Nation

When Pullman workers walked, the ARU backed them. Not just in Illinois, but across the country. Switchmen, brakemen, firemen, engineers. Men who had nothing but each other. They refused to move trains with Pullman cars.

The boycott spread like wildfire. Within days, 125,000 railway workers were in it together. Trains stopped. Mail stopped. Commerce froze. This was not chaos. It was strategy. A national strike, industrial solidarity in action. For the first time, the barons felt what it meant when labor flexed as one.

The Backlash

And that is why they crushed it.

Attorney General Richard Olney, a railroad man in government clothing, ran to court for an injunction that made the strike a federal crime. President Grover Cleveland declared the strikers a “riotous mob” and sent in the Army. Soldiers with rifles marched into Chicago not to keep peace but to keep Pullman’s profits flowing.

The newspapers played their part. Editorials smeared the strikers as anarchists.

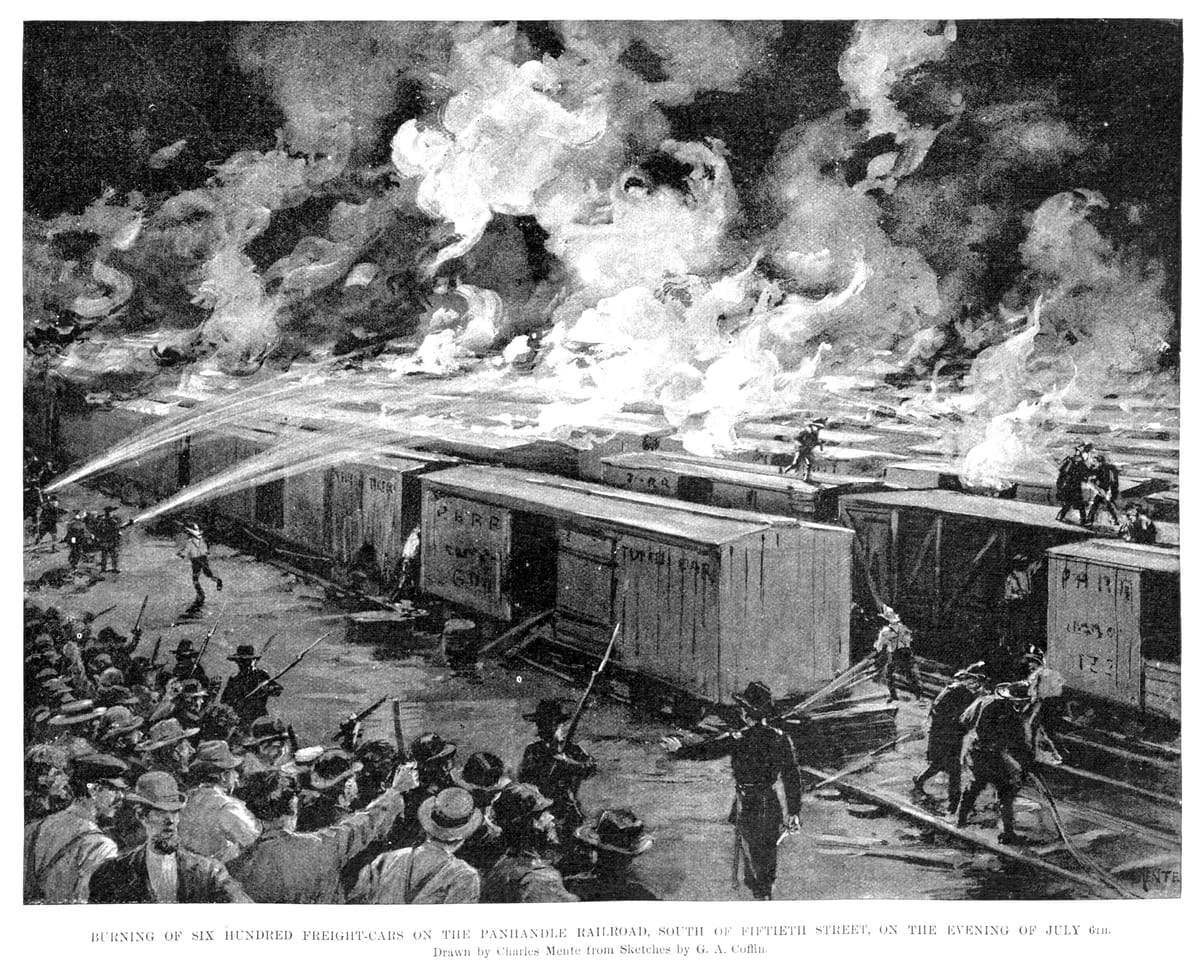

The Blood

Chicago turned into a battlefield. Crowds threw stones, tipped railcars, set fires. Soldiers fired into them. By the time it was over, at least thirty workers were dead in Chicago alone. Nationwide the toll was higher. Families buried their dead while the courts blacklisted the living.

The Cover-Up

And here’s the trick: Cleveland rushed through a federal holiday. Labor Day. A neat sop to labor, stripped of danger, shoved into September so it wouldn’t be tied to the radicalism of May Day. A holiday born not of generosity but of fear.

This is the part they don’t teach you. The holiday was not a gift. It was a cover-up.

The Echo

Fast-forward to 2025. Federal troops rolled into Los Angeles to smash protests against ICE. Weeks later, they were on the streets of Washington, D.C. The pundits called it unprecedented. It isn’t.

In 1894, Cleveland sent the Army to Chicago to break the Pullman Strike. In 2025, they’re still doing it. Different uniforms, same orders. When people rise together, power calls them a mob and sends men with guns.

The Lesson

Debs went to prison for defying the injunction. He came out more radical, more committed, more dangerous to the bosses. He told workers the only savior they’d ever see was solidarity. He said the strike was about more than wages or rents. It was about whether working people would live as free citizens or as property in Pullman’s model town. That truth has not changed.

So let’s be clear about villains. It wasn’t just Pullman. It was the rail syndicate, the judges, the editors, and a president who sent rifles into the streets. Today it is executives, governors, pundits, and presidents who call in soldiers to crush dissent. That isn’t law and order. That is fascism in practice.

Labor Day wasn’t a gift. It was a cover-up. A payoff. A warning.

The ruling class wasn’t protecting workers. They were protecting themselves. Cleveland and his allies in the railroads saw what mass action could do, and they scrambled to smother it. That’s why they pushed the holiday into September. They feared May Day, the true day of international labor, because its red banners and its memory of Haymarket tied the fight in Chicago to a global struggle. So they buried it under a safer date, meant to pacify, to hand people a parade instead of power, to buy quiet instead of conceding justice.

The eight-hour day, weekends, safety laws, child labor bans. None of it was charity. It was wrenched out of the hands of men like Pullman and Cleveland by people willing to bleed for it.

That’s the real story of this holiday.

Sources

- U.S. Department of Labor, History of Labor Day (dol.gov).

- U.S. Strike Commission, Report on the Chicago Strike of June–July 1894 by the United States Strike Commission (Government Printing Office, 1895).

- Eugene V. Debs, Speech to the Court, 1895.

- Nick Salvatore, Eugene V. Debs: Citizen and Socialist (University of Illinois Press, 1982).

- David Ray Papke, The Pullman Case: The Clash of Labor and Capital in Industrial America (University Press of Kansas, 1999).

- Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Vol. 2 (International Publishers, 1955).

- Richard Schneirov, Shelton Stromquist, and Nick Salvatore, The Pullman Strike and the Crisis of the 1890s: Essays on Labor and Politics (University of Illinois Press, 1999).

- Stanley Buder, Pullman: An Experiment in Industrial Order and Community Planning, 1880–1930 (Oxford University Press, 1967).

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Pullman Strike” (britannica.com).