Milwaukee Open Housing Marches (1967)

They called the 16th Street Viaduct Milwaukee's Mason-Dixon Line. On one side: the city's Black North Side, crammed into a ghetto called the Inner Core where landlords let buildings rot and banks wouldn't write mortgages. On the other: the all-white South Side, where Polish and Italian families wielded restrictive covenants like weapons and made damn sure no Black family would ever buy a house on their block. That half-mile bridge wasn't just infrastructure - it was the geography of American apartheid.

The Woman Who Wouldn't Quit

Vel Phillips saw the con for what it was. In 1956, she became Milwaukee's first Black alderwoman and the only woman on the Common Council - they called her "Madam Alderman" because the boys' club couldn't imagine the title fitting anyone but a man. Six years later, in 1962, she introduced an open housing ordinance to outlaw discrimination in buying and renting homes.

The vote was 18-1 against. Her vote stood alone.

She introduced it again in 1963. 18-1.

Again in 1964. 18-1.

Again in 1966. 18-1.

Again in 1967. Seventeen white aldermen sat in silence for thirty minutes while she spoke, then voted it down without a single word of debate. They wouldn't even pretend to care.

But Phillips wasn't done. And neither were Milwaukee's young people.

The Priest Who Gave a Damn

Father James Groppi grew up white and working-class on Milwaukee's South Side, the eleventh of twelve kids in an Italian immigrant family. He'd marched in Selma. He'd been to Washington with King. When he was assigned to St. Boniface Church in 1963, he landed in the heart of the Black Inner Core and saw what segregation meant up close: families with cash in hand who couldn't buy homes, landlords who charged extortion-level rent for apartments with broken heat and raw sewage, a city that built freeways through Black neighborhoods while letting white ones thrive.

In 1965, Groppi became advisor to the Milwaukee NAACP Youth Council. Together with Phillips, they decided that if the aldermen wouldn't listen to reason, they'd hear from the streets.

Two Hundred Nights of Hell

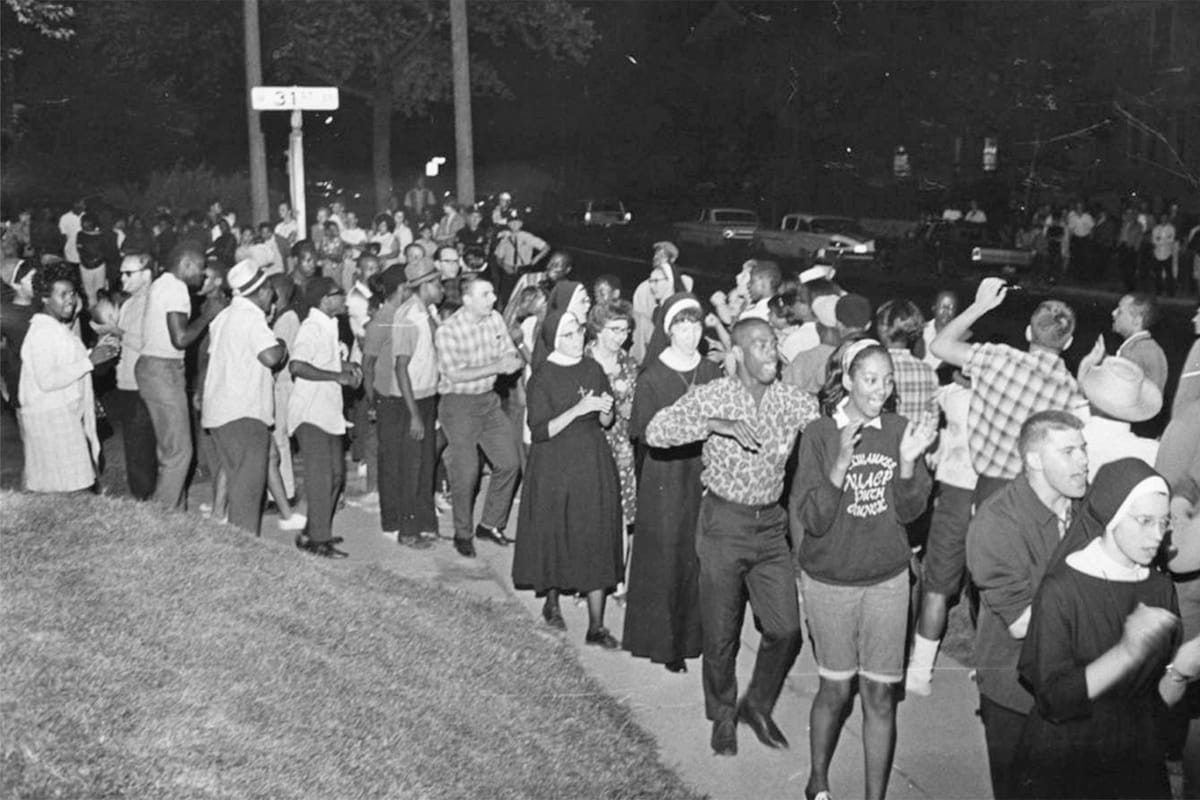

On August 28, 1967, about 200 marchers - most of them teenagers from the Youth Council - left St. Boniface Church and walked across the 16th Street Viaduct toward Kosciuszko Park on the South Side. The Commandos, a Black security unit formed after the Klan bombed the NAACP office, led the way in black berets. Phillips marched on the second night. Groppi marched every single night.

Waiting for them at the south end of the bridge: 5,000 screaming white residents. They threw rocks, bottles, cherry bombs, eggs. They threw bags of feces and urine. They held signs with racial slurs and Confederate flags. One street was blocked with a hearse bearing the words "Father Groppi's Last Ride." The marchers faced tear gas, death threats, and Groppi hanged in effigy. Young marchers like Joyce Wigley got gassed right outside St. Boniface by white counterprotesters who waited at the fence.

They marched anyway. Every single night. For 200 consecutive nights.

Mayor Henry Maier responded by banning nighttime marches for thirty days after a brief civil disturbance on July 30 that killed four people. But when thousands of white South Siders turned the marches into riots, attacking Black teenagers with impunity? Maier only suggested a "voluntary" curfew. Groppi called it what it was: a white riot. The police stood by and watched.

What It Took

The marches ended on March 14, 1968. After 200 consecutive nights. Milwaukee still had no open housing law.

Three weeks later, everything changed in the worst possible way.

On April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered in Memphis. The man who'd sent Groppi a telegram praising the nonviolence of the Milwaukee marches - shot dead on a motel balcony. Over 100 American cities erupted in flames. But not Milwaukee. The Youth Council and Commandos organized a memorial march through downtown that drew 15,000 people, the largest in the city's history. They honored King's commitment to nonviolence even as the country burned.

King's blood finally did what 200 nights of teenage courage couldn't. A week after his assassination, Congress passed the federal Fair Housing Act. Two weeks after that, on April 30, Milwaukee's Common Council - those same aldermen who'd sat in silence and voted no for six straight years - suddenly passed their own fair housing ordinance. Stronger than the federal law, even.

It took 200 nights of kids being pelted with feces and rocks. It took a white priest willing to be hanged in effigy. It took one Black woman voting alone eighteen times. And in the end, it took a martyr's bullet to make America's conscience twitch.

Even then, it barely worked. Today, Milwaukee remains one of the most segregated cities in America. The fair housing law couldn't undo decades of redlining, restrictive covenants, and white flight. It couldn't rebuild the Black neighborhoods bulldozed for freeways. It couldn't force white suburbanites to welcome Black neighbors.

Phillips became Wisconsin's first Black judge in 1971, then the nation's first Black woman elected Secretary of State in 1978. Groppi left the priesthood in 1976, married a former Youth Council member, and drove buses until brain cancer killed him in 1985. In 1988, they renamed the 16th Street Viaduct the James E. Groppi Unity Bridge.

The Mason-Dixon Line got a new name. The segregation remained.

Sources

- Patrick D. Jones, The Selma of the North: Civil Rights Insurgency in Milwaukee (Harvard University Press, 2009)

- Frank Aukofer, City with a Chance (Bruce Publishing Co., 1968)

- Jack Dougherty, More than One Struggle: The Evolution of Black School Reform in Milwaukee (University of North Carolina Press, 2004)

- UWM Libraries, March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project (Digital Archive)

- Margaret Rozga, "March on Milwaukee," Wisconsin Magazine of History 90, no. 4 (2007)

- Milwaukee Journal Sentinel archives

- Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service, "The Long March to Freedom" series (2017)