Rock Springs Massacre, 1885

On September 2, 1885, between 100 and 150 armed white men surrounded the Chinese quarter of Rock Springs, Wyoming, blocked the exits, and systematically murdered everyone they could find. Twenty-eight Chinese miners died. Fifteen more were wounded. Seventy-eight homes burned to ash. The killers were known by name. Not one was ever prosecuted.

This wasn't some spontaneous explosion of frontier violence. Rock Springs was the bloody culmination of a decade-long national campaign to terrorize Chinese workers out of America entirely.

The National Campaign

The 1870s and early 1880s were brutal for American workers. The Long Depression that started in 1873 crushed wages and threw millions out of work. Another recession hit in 1882, driving unemployment to 13 percent in some states. Railroad construction collapsed. Banks failed. Workers who'd survived the Civil War now watched their livelihoods evaporate while railroad barons and industrialists kept getting richer.

Someone had to be blamed. Chinese immigrants became the target.

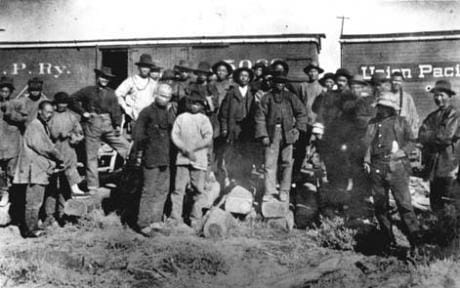

They'd come to California during the Gold Rush, fled famine and the devastation of the Taiping Rebellion in China. They'd built the transcontinental railroad through the Sierra Nevada, doing work so dangerous that white workers refused it. By the 1870s, about 100,000 Chinese lived in the American West, mostly men who sent money home to families in China. They worked for less because they had to - they were barred from most professions, denied citizenship, shut out of white society entirely.

Denis Kearney, an Irish immigrant and labor organizer, turned that desperation into a weapon. In 1877, he founded California's Workingmen's Party and blamed Chinese workers for unemployment, low wages, and every other problem facing white laborers - conveniently ignoring the railroad companies and mine owners who were actually crushing them. His rhetoric worked. It gave white workers someone to hate who wasn't their boss.

The violence came fast. In October 1871, a mob in Los Angeles lynched 17 Chinese men and boys - one of the largest mass lynchings in American history. In 1877, anti-Chinese riots exploded in San Francisco. By the early 1880s, attacks on Chinese communities were routine across the West.

Congress made it official in 1882. The Chinese Exclusion Act - the first federal law to ban immigration based on race - prohibited all Chinese laborers from entering the United States. It was supposed to be temporary. It lasted 61 years. The law sent a clear message: Chinese people were unwelcome in America. What it didn't say, but everyone understood, was that violence to enforce that message would be tolerated.

By 1885, the "driving out" campaigns were in full swing. In February, the entire Chinese population of Eureka, California - 300 people - was rounded up and expelled within 48 hours. Similar expulsions hit towns across the West. Rock Springs was next.

The Trap

The Union Pacific Railroad owned everything in Rock Springs - the mines, the company stores, the houses, the debt. When miners struck for better wages or protested the requirement to shop at overpriced company stores, Union Pacific had a solution: bring in different workers willing to accept worse terms. After strikes in 1871 and 1875, the company replaced white strikers with Scandinavian immigrants, then Chinese immigrants. It worked beautifully. For the company.

By 1885, about 331 Chinese miners worked alongside 150 white miners in Rock Springs. The Chinese had come to America fleeing famine and the chaos of the Taiping Rebellion, lured by the promise of wages ten times what they could earn at home. They'd built the transcontinental railroad, survived the Sierra Nevada winter, and proved themselves as tough and reliable as any workers in the West. But Union Pacific knew what they were doing: hire Chinese workers for lower wages, keep everyone's pay down, and watch white and Chinese miners blame each other instead of the company.

The white miners joined the Knights of Labor, one of the most powerful unions in America. The Knights had helped pass the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 - the first federal law to ban immigration based on race - and they made it clear that Chinese workers weren't welcome in their ranks. Meanwhile, Union Pacific mine managers were quietly told to hire only Chinese workers. The company wanted the cheapest labor possible, and if that meant stoking racial hatred, so be it.

Throughout the summer of 1885, threatening posters appeared in railroad towns from Evanston to Rock Springs: the Chinese had to leave Wyoming Territory or else. Chinese men were beaten in Cheyenne, Laramie, and Rawlins. Company officials ignored the warnings. The union warned them directly. Nothing changed.

On September 1, the Knights of Labor meeting hall bell rang for an evening meeting. Word spread that threats had been made against the Chinese. The next morning, the violence started.

The Massacre

At 7:00 a.m. on September 2, a fight broke out in the Number 6 mine over who had the right to work a particularly profitable section. Miners were paid by the ton, so location mattered. White miners confronted Chinese workers, shouting that they had no right to be there. A Chinese miner was beaten to death with a pick to the skull. Another was savagely beaten. A foreman broke up the fight, but instead of returning to work, the white miners went home to get their guns.

By noon, between 100 and 150 armed white men - miners, railroad workers, some with their wives and children - gathered at the railroad tracks near the Number 6 mine. The Knights of Labor hall bell rang again. More men joined. They weren't a mob. They were organized, deliberate, military in their movements.

It was a Chinese holiday. Many miners had stayed home, unaware of what was coming. Around 2:00 p.m., the armed whites split into groups and surrounded Chinatown from three directions - east, west, and from the wagon road - blocking the bridges over Bitter Creek so no one could escape. They moved through the Number 3 mine first, shooting Chinese workers where they stood.

Leo Dye Bah was killed near the western end of Chinatown. Yip Ah Marn died on the eastern side. As word spread, terrified Chinese miners ran in every direction - up the hills, across Bitter Creek, through the sagebrush, anywhere away from the guns. White attackers stopped fleeing men, demanded to know if they had weapons, then robbed them of watches and any gold or silver before letting them go. Others weren't so lucky.

The mob torched every structure in Chinatown. Seventy-eight homes went up in flames. Men hiding in cellars burned alive. Leo Sun Tsung, 51 years old, was found in his hut, his body covered in wounds, his left jawbone shattered by a bullet. Leo Kow Boot, 24, was shot through the neck at the base of the mountain. Sia Bun Ning's charred remains were found near the Chinese temple - only his head, neck, and shoulders were left. Leo Lung Hong, Leo Chih Ming, Liang Tsun Bong - their bodies burned beyond recognition, only pieces left to identify.

Those who made it out alive fled into the hills and prairies, some wounded, all traumatized, many dying from thirst, cold, and untreated injuries in the days that followed. By nightfall, Chinatown was ash. The official count was 28 dead, 15 wounded. But many who ran were never seen again. The real number might have been 50 or more.

The Aftermath

Governor Francis E. Warren arrived in Rock Springs the next day. He met with company officials and white miners. The miners had demands: no Chinese would ever live in Rock Springs again, no one would be arrested for the murders, and anyone who objected would be hurt or killed. Warren, to his credit, rejected these terms and telegrammed President Grover Cleveland for federal troops. On September 9, six companies of soldiers arrived to restore order.

But here's the cruelest part: the company told the surviving Chinese miners they'd be taken by train to San Francisco. Instead, the train stopped in Rock Springs. Federal troops escorted them back to the scorched ground where their homes had been, where their friends' bodies still lay in the open, rotting, half-eaten by dogs and hogs. The company wanted them back in the mines. Coal had to flow. Profits had to be protected.

The massacre made national headlines. Eastern newspapers like The New York Times condemned the violence. Thomas Nast drew a scathing cartoon showing a Chinese diplomat observing the slaughter, saying, "There's no doubt of the United States being at the head of enlightened nations." But Wyoming newspapers were sympathetic to the white miners. The Laramie Boomerang said it "regretted" the riot but found the circumstances understandable. The local Rock Springs Independent warned that if Chinese workers returned, "Rock Springs is killed, as far as White men are concerned."

Union Pacific eventually fired 45 white miners. But not one was prosecuted for murder. Not one was charged with arson. The identities of the killers were widely known - witnesses could name them - but no one testified in court because Chinese testimony wasn't admissible against whites in many Western territories. No one faced justice.

President Cleveland, under pressure from the Chinese government, convinced Congress to pay $150,000 in reparations to the victims and survivors. But the money came without apology, without accountability, without acknowledgment of what had actually happened. It was blood money.

The Chinese miners stayed. Some continued working Union Pacific mines for decades, protected by federal troops stationed at Camp Pilot Butte until 1898. But the message was clear: your labor is wanted, your lives are disposable, and if white workers decide to kill you, the law won't stop them.

What We Carry

Rock Springs was one of the deadliest anti-Chinese massacres in American history, but it wasn't unique. Similar violence erupted across the West - Los Angeles in 1871, Hells Canyon in 1887, dozens of smaller attacks that never made headlines. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 had sent a message: these people don't belong here. Rock Springs proved how far Americans were willing to go to enforce that belief.

The massacre worked. The Knights of Labor got what they wanted - proof that Chinese workers could be terrorized and driven out. Union Pacific got what it wanted - cheap labor kept in line by fear. And white workers got what they thought they wanted - the satisfaction of knowing they could murder with impunity, even if their wages stayed just as low.

This is the same pattern repeated over and over in American labor history: corporations exploit racial divisions to break unions and keep wages down, workers turn their rage on each other instead of their bosses, and the people with the least power pay in blood. Ludlow. Tulsa. Countless others.

Rock Springs should have been a turning point. Instead, it was a blueprint.

Sources

- Tom Rea, "The Rock Springs Massacre," WyoHistory.org, Wyoming State Historical Society

- Memorial of Chinese Laborers at Rock Springs, Wyoming Territory to the Chinese Consul at New York (1885), reprinted in Cheng-Tsu Wu, ed., Chink! A Documentary History of Anti-Chinese Prejudice in America

- Report of Imperial Chinese Consulate-General, San Francisco (September 30, 1885), Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States

- Erika Lee, At America's Gates: Chinese Immigration During the Exclusion Era, 1882-1943

- Library of Congress, "Rock Springs Massacre: Topics in Chronicling America"

- "A Deadly Conflict Between White Miners and the Chinese at Rock Springs, Wyoming Territory," Harper's Weekly, September 9, 1885