San Francisco General Strike, 1934

By 1934, the Great Depression had gutted America. One in four workers couldn't find a job. Families were losing their homes, their farms, their futures. Unemployment had hit 25% at its worst in 1933, and even as things improved slightly, millions remained desperate. Roosevelt's New Deal promised relief, but the National Industrial Recovery Act - which was supposed to give workers the right to organize - turned out to be mostly words on paper when employers decided to ignore it.

Into this wreckage stepped workers who'd had enough of begging. In San Francisco that July, around 150,000 of them shut down an entire city for four days in solidarity with dockworkers fighting for dignity. It was the first time a major American port city ground to a complete halt. And it happened because the police murdered two men for the crime of wanting control over who got hired and who got left to starve.

Begging for Work

Every morning before 1934, longshoremen lined up on San Francisco's docks for the shape-up. Private contractors walked the line and pointed at whoever they wanted. If your face didn't fit, if you didn't slip the boss a bribe, if you'd complained about safety or hours, you went home with nothing. The favored gangs got steady work. Everyone else scrambled for scraps. Some men worked 20-hour shifts and went home too exhausted to speak. Others got a few hours a week and watched their families go hungry. The company union - the Blue Book - existed to make sure you kept your mouth shut.

Roosevelt's National Industrial Recovery Act passed in 1933, promising workers the right to organize. Longshoremen saw an opening. By early 1934, a rank-and-file movement led by a quiet Australian dockworker named Harry Bridges was demanding union recognition, a coast-wide contract, shorter shifts, better wages, and most importantly, union control of hiring. No more begging. No more bribes. Just a fair rotation.

When employers refused even to negotiate, 12,000 longshoremen up and down the West Coast walked out on May 9, 1934. Sailors and teamsters joined them. Every port from San Diego to Seattle went silent.

The Long Fight

For nearly two months, the strike held. Employers tried everything. They housed strikebreakers on ships, drove them through picket lines under armed guard, and got friendly newspapers to scream about communist conspiracies. In San Pedro on May 15, company goons opened fire on strikers, killing two men - Dick Parker and John Knudsen. The violence only hardened resolve.

In San Francisco, the Industrial Association - a coalition of shipping companies, banks, railroads, and utilities formed specifically to crush unions - coordinated the employer offensive. They had money, guns, political connections, and the full backing of the police. What they didn't have was the ability to move freight without workers. Ships piled up. Cargo rotted. The strike was costing employers a million dollars a day.

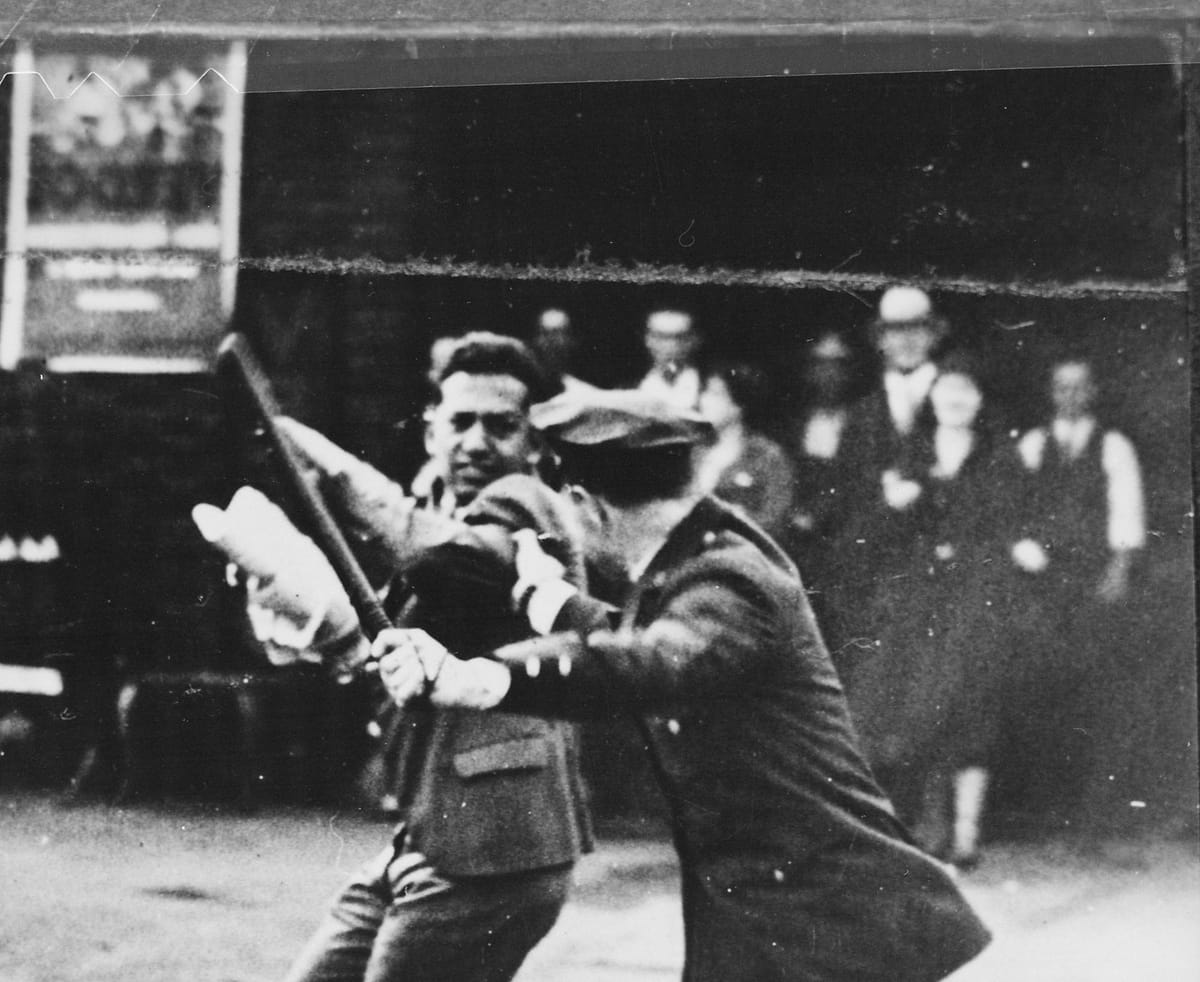

On July 3, the Industrial Association decided to break the strike by force. They brought in scabs, mobilized a thousand cops, and announced they'd reopen the port. For two days, pitched battles raged along the Embarcadero. Police on horseback charged strikers. Men threw bricks and tear gas canisters back at cops. Trucks got overturned. Blood ran in the streets.

Bloody Thursday

July 5, 1934. The cops came ready to kill.

Around midday, police opened fire on strikers near the intersection of Mission and Steuart Streets. Howard Sperry, a longshoreman and World War I veteran, was shot and killed. Charles Olsen was shot but survived. Nick Bordoise - born Nicholas Counderakis in Greece, an out-of-work cook who'd been volunteering at the union's strike kitchen - was shot in the back. He managed to stumble around a corner before collapsing. He died hours later.

More than 60 others were wounded. Police fired on the union hall itself, lobbing tear gas through windows. Someone called the hall and asked, "Are you willing to arbitrate now?" The answer was no.

Governor Frank Merriam sent in 1,700 National Guard troops with machine guns and orders to shoot to kill. They ringed the waterfront with barbed wire. Freight started moving again under military protection. The employers thought they'd won.

They were wrong.

The Funeral That Changed Everything

On Monday, July 9, San Francisco held its breath. Forty thousand people filled Market Street for the funeral procession of Howard Sperry and Nick Bordoise. The march stretched more than a mile. Strikers, their families, and supporters walked in complete silence. No police showed up - they knew better.

The city had witnessed a massacre, and the mood shifted. These weren't radicals or criminals. They were working men murdered for asking to be treated like human beings. Public opinion swung hard toward the strikers. Within days, union after union voted to join them. By July 16, the San Francisco Labor Council called a general strike.

At 8 a.m. that Monday, 150,000 workers around the Bay Area laid down their tools. Streetcars stopped. Restaurants closed. Construction halted. The city went quiet. For four days, San Francisco was a union town.

The Red Scare

The response was predictable. Every newspaper in the city - particularly the Hearst papers - shrieked about a communist revolution. The Los Angeles Times called it "an insurrection, a Communist-inspired and led revolt against organized government." National Recovery Administrator Hugh Johnson gave a speech at UC Berkeley calling the strike "a menace to the Government." Vigilante mobs, protected by police, rampaged through the city smashing union halls, leftist meeting places, and anyone they thought looked radical. Over 450 people were arrested and crammed into a jail built for 150.

Was it a communist plot? Of course not. Bridges worked with communists, accepted their help, and never apologized for it. But the central demand - control over hiring - was the same fight longshoremen had been waging for 50 years. In 1893, employers called striking sailors "anarchists." In 1934, they called them "communists." They use the same slurs today.

The real threat wasn't ideology. It was workers realizing their own power.

The Betrayal and the Win

The general strike frightened the conservative leaders of San Francisco's Labor Council almost as much as it scared employers. They'd opposed the maritime strike from the start, and now they controlled the General Strike Committee. They immediately started granting exceptions. Streetcar operators went back to work. Ferryboat workers never joined. Newspapers kept printing anti-strike propaganda with union typesetters at the presses.

By July 19 - just four days after it started - the general strike was over. Labor Council leaders, desperate to appear respectable, had killed it.

But the longshoremen didn't lose. On July 31, they voted to accept arbitration and returned to work. The arbitration board awarded them most of what they'd fought for: a coast-wide contract, wage increases, shorter shifts, and a jointly controlled hiring hall with a union-elected dispatcher. It wasn't full union control, but it was enough to end the shape-up and protect union members from being blacklisted.

More importantly, the strike broke something open. It proved that solidarity worked. Within a few years, Bridges led the Pacific Coast longshoremen out of the conservative AFL and formed the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union, which became one of the most democratic and militant unions in the country.

What They Won and What We Lost

Nobody was ever held accountable for murdering Sperry and Bordoise. The cops who shot them went home to their families. Governor Merriam's career continued unscathed. The vigilantes who terrorized the city faced no consequences.

But the longshoremen won something the employers could never take back: dignity. The 1934 strike, along with the Minneapolis Teamsters strike and the Toledo Auto-Lite strike that same year, helped spark the industrial union movement that built the CIO and changed American labor forever.

The ILWU still shuts down every West Coast port on July 5 to honor Bloody Thursday. They honor not just Sperry and Bordoise in San Francisco, but Dick Parker and John Knudsen in Los Angeles, Shelvy Daffron in Seattle, and all the workers who paid in blood for the simple right to work without groveling.

That's the legacy: workers who stood together, who refused to be driven like cattle, who looked at the police and the National Guard and the entire weight of capital lined up against them and said no. For four days, they owned their city. And they forced the bosses to remember that without labor, nothing moves.

Sources

- Paul S. Taylor and Norman L. Gold, "San Francisco and the General Strike," Survey Graphic, September 1934

- Mike Quin, The Big Strike (1949)

- Bruce Nelson, Workers on the Waterfront: Seamen, Longshoremen, and Unionism in the 1930s (1988)

- Howard Kimeldorf, Reds or Rackets? The Making of Radical and Conservative Unions on the Waterfront (1988)

- David F. Selvin, A Terrible Anger: The 1934 Waterfront and General Strikes in San Francisco (1996)

- Robert W. Cherny, Harry Bridges: Labor Radical, Labor Legend (2023)

- ILWU Oral History Collection and Bloody Thursday commemorations

- FoundSF.org historical archives

- Zinn Education Project materials on the 1934 strike