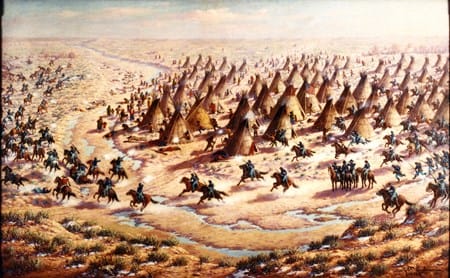

Sand Creek Massacre, 1864

They flew the American flag. They flew a white flag beneath it. The soldiers shot them anyway.

Content Warning: This entry contains graphic descriptions of violence.

On November 29, 1864, approximately 675 U.S. troops surrounded a camp of 750 Cheyenne and Arapaho people who'd been promised federal protection. Most were women, children, and elders. The peace chiefs had surrendered their weapons. They believed they were safe.

They weren't.

By nightfall, at least 150 were dead - butchered, mutilated, scalped. Soldiers cut off genitals and wore them as hat bands. They made tobacco pouches from scrotums. They beat children's brains out with rifle butts. Then they went home to Denver and paraded through the streets as heroes.

This wasn't war. It was extermination.

What They Wanted

White people found gold in 1858. That's all it took. The 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie had promised the land to the Cheyenne and Arapaho. Denver was built on Arapaho territory anyway. Within three years, thousands of white settlers were trespassing. By 1861, the government forced a new treaty that took away 93% of their land.

The Southern Cheyenne split over what to do. The peace chiefs - Black Kettle, White Antelope, Lean Bear - believed negotiation was the only path to survival. They'd watched their people die from cholera, watched the buffalo disappear, watched promises break. They chose diplomacy because war meant extinction.

The Dog Soldiers chose war. They raided wagon trains and settlements through 1864. The peace chiefs condemned the raids. They knew it would doom them all.

Governor John Evans and Colonel John Chivington didn't care about the difference. They wanted all Indians gone. Evans authorized a militia specifically to kill them. Chivington, a Methodist preacher, called them "heathen savages" and gave explicit orders: kill Cheyennes wherever found.

In September 1864, Black Kettle and White Antelope went to Denver to negotiate. Evans told them to report to Fort Lyon for protection. Black Kettle made a choice: take the vulnerable to safety while the warriors stayed away. About 750 people - mostly women, children, elders - went to Sand Creek. They surrendered weapons. They raised the American flag. They believed the promise of protection.

The peace chiefs were trying to save their people. Instead, they led them to slaughter.

November 29, 1864

Before dawn, 675 soldiers surrounded the camp. When the sun rose, Black Kettle raised the flags higher and walked toward them with other chiefs. They thought it was a misunderstanding.

The troops opened fire.

George Bent, twenty-four years old, half-Cheyenne and half-white, was sleeping in his lodge when the shooting started. He saw everything. Women and children ran for the creek bed, digging frantically into the sand with their hands. Soldiers followed them in and kept shooting. Bent was shot in the hip but survived to tell the story.

White Antelope, seventy-five years old, stood in front of his lodge. He folded his arms across his chest and sang his death song: "Nothing lives long, only the earth and mountains." Soldiers shot him down, then cut off his nose, ears, and genitals. They made his scrotum into a tobacco pouch.

One witness: "I saw one squaw cut open, with an unborn child lying by her side."

Another: A six-year-old girl walked toward the troops holding a white flag on a stick. She took a few steps. They shot her dead.

Captain Silas Soule refused the order. He knew these people were peaceful. When Chivington ordered the attack, Soule called him a "low-lived cowardly son of a bitch" and threatened to shoot any of his own men who fired. Another officer, Lieutenant Joseph Cramer, did the same. Most officers followed orders.

The massacre lasted six to eight hours. Soldiers scalped infants. They beat children's brains out with rifle butts. They cut off fingers for the jewelry. They shot women begging on their knees. They hunted survivors through the creek bed and shot them in their hiding places.

At least 150 dead, probably more. Two-thirds women and children. Among them: White Antelope, One Eye, Yellow Wolf, Big Man, War Bonnet, Spotted Crow, Bear Robe, Standing Water - peace chiefs, Council of 44 members, elders who'd chosen diplomacy. Left Hand, the Arapaho chief who'd also chosen peace, was killed. His band was nearly wiped out.

Black Kettle survived. His wife, Medicine Woman Later, was shot nine times and left for dead in the creek bed. He found her in the darkness and carried her through the freezing night. She lived, carrying those wounds forever.

Nine soldiers died, most from friendly fire.

The survivors fled north through winter with nothing - no lodges, no winter provisions, no sacred items. Just trauma and rage.

What Happened Next

The troops paraded through Denver displaying scalps. Chivington claimed 500 warriors killed. He was celebrated as a hero.

Silas Soule wrote letters describing what he'd witnessed. He testified before three government investigations. All three condemned the massacre. Two months after his testimony, on April 23, 1865, Soule was shot in the face on a Denver street by a soldier who'd been at Sand Creek. He died instantly, age 26, married three weeks. The assassin escaped jail. Another witness died of mysterious poisoning. Chivington resigned before court-martial. He faced no charges. Governor Evans resigned but lived comfortably. No one was punished.

The Cheyenne and Arapaho learned the lesson: peace gets you murdered.

In January 1865, survivors joined with Dog Soldiers and other warriors in massive coordinated raids across Colorado and Kansas. Julesburg was burned. Wagon trains destroyed. Ranches attacked. The U.S. called it unprovoked violence. The tribes called it retaliation for genocide.

Sand Creek didn't just kill 150 people. It killed the peace faction's credibility. War chiefs had warned that the Americans couldn't be trusted. Sand Creek proved them right. For the next decade, Plains warfare intensified - a direct line from Sand Creek to the Fetterman Fight, the Washita massacre, Little Bighorn, Wounded Knee.

Black Kettle kept trying. In 1867, he signed the Treaty of Medicine Lodge Creek, still believing diplomacy could work. It didn't. On November 27, 1868, George Armstrong Custer attacked his village on the Washita River at dawn, just like Sand Creek. Black Kettle and Medicine Woman Later were both killed. He died still believing in peace that would never come.

The Erasure

For 143 years, textbooks called it a battle. A statue honoring Colorado's Civil War soldiers stood outside the state capitol until 2020, listing Sand Creek among the territory's "battles." The massacre was taught as legitimate military action against hostiles.

The exact location was lost. Even soldiers who'd been there couldn't agree on the spot when they tried to return in 1908. The site became someone's ranch land. Descendants spent decades searching for their ancestors' burial ground.

Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site wasn't established until 2007. By then, most Americans had never heard of it.

The victims had names: Seven Bulls, Bear Shield, Little Bear, Spotted Horns, Empty Belly, Four Bears, Old Bear, Walking Crane, and dozens more whose names survive in Cheyenne oral histories. They were farmers, hunters, parents, elders. People who believed peace was possible. The fact that we don't know most of their names is part of the crime.

George Bent spent the rest of his life documenting what happened, writing letters to historians, making sure someone remembered the truth. Without him, even more would have been lost.

Silas Soule's grave in Denver's Riverside Cemetery is marked with a simple stone. Every November, Cheyenne and Arapaho descendants stop there during the Healing Run to honor the white officer who refused to murder them. A plaque was installed downtown in 2010, 145 years late, near where he was assassinated. Most Coloradans still don't know his name.

That's what forgetting does. It erases the witnesses. It buries the crimes. It lets genocide get rebranded as military necessity and teaches the next generation that some massacres were somehow justified.

The trauma didn't end in 1864. It lives in descendants who carry the weight of what was done to their grandparents and great-grandparents. Sand Creek isn't history. It's memory. It's grief that doesn't fade.

The blood is still in the sand.

Sources

- National Park Service, Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site

- Ari Kelman, A Misplaced Massacre: Struggling Over the Memory of Sand Creek (2013)

- Stan Hoig, The Sand Creek Massacre (1961)

- David Halaas and Andrew Masich, Halfbreed: The Remarkable True Story of George Bent (2004)

- Elliott West, The Contested Plains: Indians, Goldseekers, and the Rush to Colorado (1998)

- U.S. Congress, Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War (1865)

- Sand Creek Massacre Foundation

- Tom Bensing, Silas Soule: A Short, Eventful Life of Moral Courage (2005)