The Battle of Blair Mountain, 1921

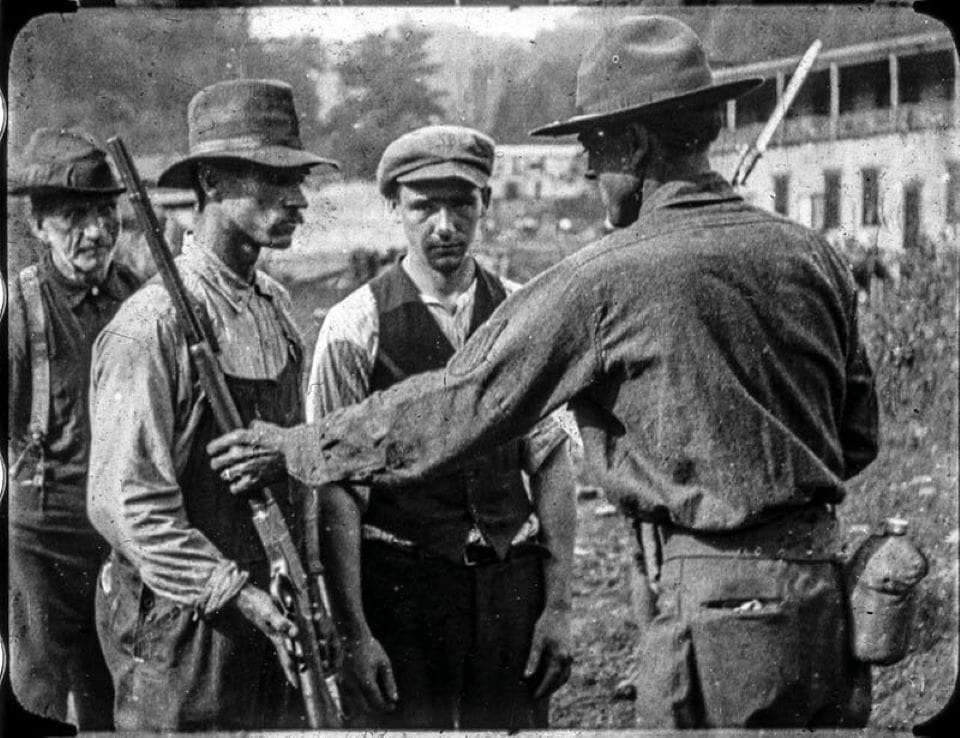

Ten thousand armed coal miners marching through West Virginia hollows, red bandanas tied around their necks, rifles in hand - this wasn't some movie. This was August 1921, and it was the largest armed uprising on American soil since the Civil War. For five days, machine guns rattled across mountain ridges while homemade bombs fell from the sky. The miners called themselves the Redneck Army. The coal barons called them terrorists. What they were was desperate.

The Empire Built on Backs and Bones

West Virginia coal country wasn't just dangerous work. It was a feudal system dressed up as capitalism. Coal companies owned everything - the houses, the stores, the schools, even the currency. Miners got paid in scrip, company money that was worthless anywhere else. They bought overpriced goods at company stores, lived in company houses, and sent their kids to company-controlled schools. Step out of line? Get fired, evicted, blacklisted. The companies hired armies of private detectives - thugs from the Baldwin-Felts agency - to crush any whisper of union organizing. In Logan County, Sheriff Don Chafin ran the operation, pocketing over $32,000 a year from the coal operators to keep the United Mine Workers out. That's more than half a million in today's money.

This wasn't just West Virginia's problem. Coal powered America's industrial explosion. Railroads, steel mills, factories - they all ran on coal dug by men trapped in a system designed to bleed them dry. Nationally, unions were fighting similar battles from Pennsylvania to Kentucky, but nowhere was the repression more complete than in southern West Virginia's coal counties.

The Spark

May 19, 1920. Matewan, West Virginia. Baldwin-Felts detectives rolled into town to evict union miners from company housing. Police Chief Sid Hatfield, who actually gave a damn about the miners, confronted them. Somebody fired. When the smoke cleared, seven detectives lay dead on Mate Street, including the agency founder's two brothers. So did Mayor Cabell Testerman and two miners. Hatfield became a hero overnight.

Fifteen months later, on August 1, 1921, Hatfield and his deputy Ed Chambers walked up the courthouse steps in Welch, their wives beside them. They were unarmed. The Baldwin-Felts agents waiting at the top were not. They opened fire. Hatfield died instantly. An agent walked down and shot Chambers in the back of the head while his wife Sally screamed. The killers walked. The message was clear: resist and die, and no one will do a damn thing about it.

The March

Thousands of miners poured out of the mountains, furious and armed. By August 20, somewhere between 10,000 and 15,000 men had gathered at Lens Creek, many of them World War I veterans. They tied red bandanas around their necks - that's where "redneck" comes from, solidarity with working people, not the slur it became. Black miners, white Appalachian hill folk, Polish and Italian immigrants - the companies had kept them divided by race and language for decades, but at Blair Mountain they fought together. They organized medical units, supply lines, guard rotations. This wasn't a mob. It was an army.

Their plan: march through Logan County to free jailed union miners in Mingo County and end martial law. First, they had to get past Sheriff Don Chafin and the 3,000 deputies and mine guards he'd assembled on Blair Mountain's ridgeline, funded entirely by coal company money. Chafin had machine guns. He had trenches. He even had three private biplanes.

Five Days of War

August 31, 1921. A minister named John Wilburn led 70 miners up the mountain at dawn. They ran into Chafin's deputies. In the firefight, miner Eli Kemp, who was Black, was shot dead. Wilburn killed the deputy who'd shot him. The battle was on.

For five days, gunfire echoed across the mountain. Miners attacked repeatedly, trying to flank the entrenched positions. Chafin's machine guns mowed them down. His planes dropped homemade pipe bombs packed with nuts and bolts for shrapnel, the first time American citizens were bombed from the air on U.S. soil. An estimated one million rounds were fired. Bodies piled up. Exact numbers? Nobody knows. Maybe 30 dead on Chafin's side. Somewhere between 50 and 100 miners killed, though some historians think it was higher. The coal companies made damn sure nobody counted.

President Warren Harding finally sent in federal troops on September 2. The miners, many of them veterans, laid down their weapons when they saw American soldiers. They weren't rebelling against their country. They were fighting a private army funded by coal barons who'd bought the law.

The Reckoning That Never Came

The state of West Virginia charged 925 miners with murder, conspiracy, and treason. Most were acquitted, but the legal battles bankrupted the United Mine Workers. Union membership collapsed. The companies won. Chafin? He kept his job until 1924, when he was finally convicted - not for the massacre, but for bootlegging. He served ten months, moved to Huntington, bought a building, and died rich in 1954. The Baldwin-Felts agents who murdered Sid Hatfield and Ed Chambers? Never charged.

The miners got nothing. Union organizing in southern West Virginia stayed dead until the New Deal forced coal operators to recognize workers' rights in 1933. It took another dozen years, federal intervention, and a complete shift in American labor law to give miners what they'd fought for at Blair Mountain: the right to organize without being murdered for it.

The battle faded from history, buried like the bodies in unmarked graves. For decades, textbooks ignored it. When Blair Mountain was finally added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2009, the decision was reversed months later after coal companies complained. They wanted to strip-mine the battlefield. In 2018, it was restored to the register, but the fight to preserve it continues.

Blair Mountain wasn't a riot. It was a war fought by working people who'd been pushed past breaking. They lost, but their defeat helped spark the labor protections we take for granted today. Remember that the next time someone tells you unions are unnecessary. People died on that mountain for the forty-hour week, for workplace safety laws, for the very idea that workers deserve dignity. The least we can do is remember their names.

Sources

- National Park Service, "The Battle of Blair Mountain," West Virginia Mine Wars Museum

- Kenneth R. Bailey, "Battle of Blair Mountain," e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia

- Robert Shogan, The Battle of Blair Mountain: The Story of America's Largest Labor Uprising, Westview Press, 2004

- Lon Savage, Thunder in the Mountains: The West Virginia Mine War, 1920-21, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1990

- Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Battle of Blair Mountain newspaper archives

- David A. Corbin, Life, Work, and Rebellion in the Coal Fields, University of Illinois Press, 1981