The Battle of Virden: 1898

Today’s Post

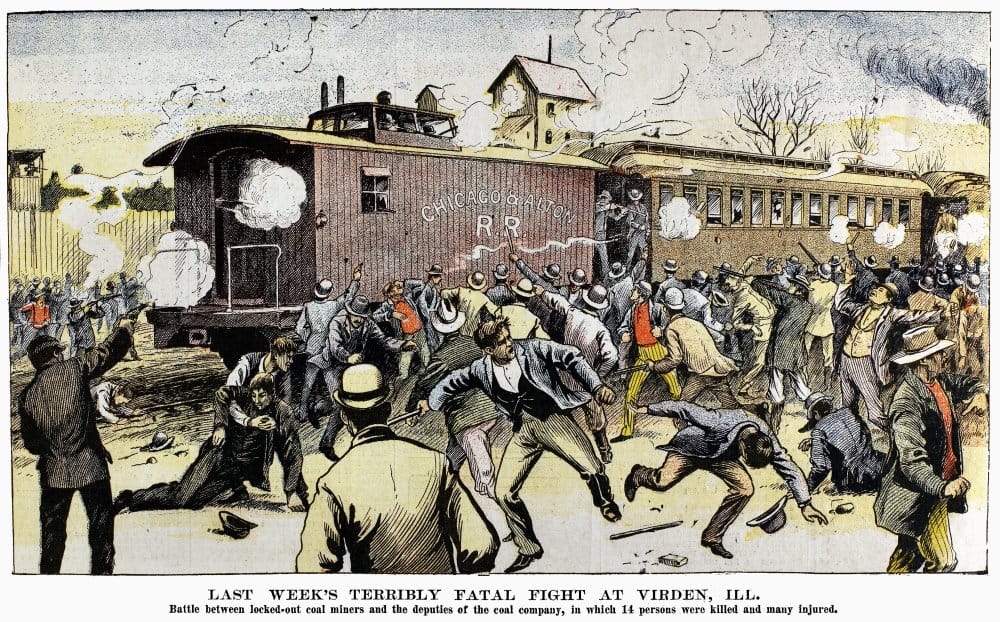

On October 12, 1898, a train rolled into Virden, Illinois with rifles poking out the windows. The Chicago-Virden Coal Company had turned its mine into a stockade and loaded a train with hired gunmen and duped strikebreakers. This wasn’t a dispute over wages. It was a setup for slaughter, and everyone in town knew it.

The Setup

The long hangover from the Panic of 1893 had miners starving. Operators cut pay to the bone and refused to recognize the United Mine Workers. The Chicago-Virden Coal Company decided to break the union by force. They fenced off the mine like a damn fortress, stacked it with guards, and sent recruiters to Alabama with fat lies about steady jobs up north.

The men on that train - mostly Black miners from Birmingham - had been conned. Told there was no strike. Told they’d be safe. They weren’t enemies, they were pawns. The company wanted them marched straight into a war zone so wages could be cut and the union smashed. Divide and conquer, with blood in the middle.

October 12, 1898

By noon the train crawled into town. On the ground, thousands of union miners and their families crowded the depot and the stockade fence. Mothers clutched children’s hands, wives stood alongside their husbands. A Chicago paper wrote that “the cars were loop-holed for rifles, the men inside blazing away as though it were war.” And that’s exactly what it was.

Gunfire ripped loose almost as soon as the cars slowed. Hired guards shot from the train windows. Miners fired back from the cinders. For minutes it was a straight-up war in the middle of a prairie town.

When the smoke cleared, seven union miners lay dead: Ernest Kitterman, father of four. Edward Welch, a young miner only two years married. John R. Boney, who had sweated in the pits for decades. Alongside them fell Frank Burch, Fred Boal, Ernest Long, and Joe Gitterle. Five company guards were killed as well. Dozens more on both sides were wounded, estimates ranging between 30 and 40 men bleeding out in the dirt.

But the train never broke through. It backed out and ran. The strikebreakers never touched the mine.

Imagine the men inside those cars, realizing too late they had been lied to. They weren’t breaking a strike. They were being driven into a kill zone. Some never left the train, staring out at the bloodshed their bosses had engineered.

The Governor’s Call

Illinois Governor John Tanner, to his credit, told the company to go to hell. He refused to send troops to guard their stockade. After the shooting stopped, he sent militia - not to crush the strike, but to stop any more trains of strikebreakers. His words were blunt: “No armed body of men shall come into this state and attempt to take the place of our striking miners.” That almost never happened in America. For once, the state didn’t serve as the bosses’ hired guns.

What Followed

Virden became holy ground for the union. Under John Mitchell, the UMWA turned the massacre into fuel for organizing. Mitchell called it “a great victory bought with the blood of our comrades.” The company caved to the statewide wage scale, and the union took root in Illinois coal. The eight hour day edged closer to reality. But victory was soaked in blood. Funerals filled Virden’s streets. Widows in black trailed behind plain wooden coffins, children walked silent with heads down. The community carried those images for generations.

On Race and Power

The bosses knew exactly what they were doing when they recruited Black miners from the South. They wanted white and Black workers at each other’s throats so no one could fight the real enemy. The men on that train weren’t the villains. They were working people, lied to and shoved into the line of fire. The real blame rests with the company that armed a train, built a fortress, and tried to turn poverty into a weapon.

Why It Matters

Virden proves a point we’d better not forget: when workers stood together and the state didn’t side with the stockade, they could win. But the price was blood in the streets of a small Illinois town. This wasn’t some metaphorical class war. It was rifles and bodies on the cinders. And the same damn playbook - divide by race, call in private armies, cry “law and order” - still gets used today.

Sources

- Bogue, Allan G. The Earnest Men: The Growth of the Union Movement in Illinois, 1890-1900. University of Illinois Press, 1955.

- Lindquist, David. “The Virden Mine Riot of 1898.” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Vol. 51, No. 4 (1958).

- Dubofsky, Melvyn, and Warren Van Tine. John L. Lewis: A Biography. University of Illinois Press, 1977. (Background on UMWA organizing).

- Illinois State Historical Library, contemporary newspaper clippings (Chicago Tribune, October 13, 1898; St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 14, 1898).

- United Mine Workers Journal, October 1898 issues (statements by John Mitchell).