The Chicago Race Riot of 1919

They Called It a Riot

Hint: it wasn't a riot. They called this a riot because that excused white America from taking responsibility. It wasn’t a riot in any fair sense of the word, it was a white mob attacking Black neighbors, burning homes, and killing with impunity. The language shifted the blame away from the aggressors and onto the victims.

Unlike the Seattle General Strike earlier that year, which shut a mostly white city down without a shot fired, Chicago in the summer of 1919 exploded in racist violence. This was the bloodiest chapter of what came to be called the Red Summer, when white mobs across the country terrorized Black communities under the guise of protecting “order.”

The Spark

On July 27, 1919, seventeen-year-old Eugene Williams, the son of Black migrants from the South, and some friends built a raft to beat the summer heat, which had pushed into the 90s. When the raft drifted too close to the segregated white section of a Lake Michigan beach, white men hurled rocks. They stoned Eugene until he drowned, in front of hundreds of white beachgoers who did nothing. When Black beachgoers demanded police intervention, they were attacked. Picture that today: someone willfully murdering a boy in the lake, and when you try to stop them, the crowd turns on you. What kind of anger would you carry after that? That refusal to protect or deliver justice lit the fuse.

In 1919, Chicago’s white establishment was already racist as hell, and ready to lash out at Black neighbors. The Great Migration had brought tens of thousands of Black families from the South in search of better jobs and freedom from Jim Crow. They ran into rigid segregation in housing, jobs, and public space. White veterans returned from World War I demanding work as industries laid off wartime labor, and politicians and papers stoked resentment, painting Black migrants as the problem. Across the country, the so-called Red Summer saw similar racist violence in Washington D.C., Knoxville, Omaha, and more. Chicago’s riot was not an accident. It was part of a nationwide backlash against Black progress.

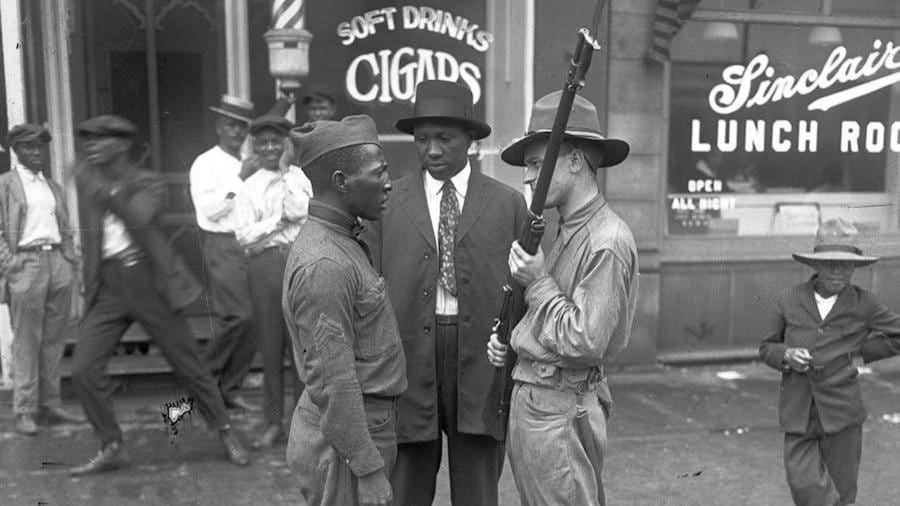

The Violence

For nearly a week, white mobs numbering in the thousands surged into Black neighborhoods on Chicago’s South Side. They set homes and businesses on fire, dragged people from streetcars, and beat strangers to death in the open. The Illinois National Guard eventually deployed 6,000 troops, but soldiers often looked the other way. The Chicago Police Department was even worse: officers refused to arrest white attackers, but hauled in Black residents for defending themselves. By the time it ended, 38 people were dead (23 Black and 15 white), more than 500 wounded, and over a thousand Black families left homeless as their houses and shops burned. Property losses reached into the millions, wiping out lifetimes of Black wealth in a matter of days.

A Pattern of Panic

The papers framed it as “race trouble,” a phrase that shifted blame from the mob to the community under attack. But make no mistake: this was a massacre fueled by moral panic, by the deliberate scapegoating of Black neighbors as threats to jobs, housing, and public safety. It wasn’t spontaneous. It was incited, inflamed, and then excused by demagogues and the wealthy who were more than happy to have the working class tear itself apart.

The People Fought and Died

Eugene Williams never got to grow up, drowned in Lake Michigan after being stoned by white men. John Mills, a Black veteran who had served his country in France, was murdered defending his own block. Mothers and children fled burning homes with nothing but the clothes on their backs. In all, 23 Black Chicagoans were killed. They were laborers, veterans, porters, seamstresses, fathers and daughters. They weren’t faceless victims of “unrest.” They were people with families and futures stolen. More than a thousand Black families lost everything when their houses were torched. Black communities destroyed.

And they didn’t all go quietly. Like John Mills, Black veterans, fresh from the trenches of World War I, armed themselves and defended their homes and families. Neighbors set up barricades to keep mobs out. For the first time in Chicago’s history, Black neighborhoods fought back with organized armed defense. The South Side’s “Black Belt” became a fortress, with veterans posting watches and women running kitchens to keep defenders fed. Shots rang out both ways, and for a moment it was clear: these communities would not simply be erased. Their resistance did not stop the deaths or the burnings, but it saved lives, and made plain that Black Chicagoans would not accept slaughter in silence.

We remember a few names because records caught them, but most of the 23 Black dead remain little more than lines in coroner’s reports, often marked only as “Negro male.” Even in death, they were denied dignity. That erasure was no accident - it was part of the same system that allowed the violence in the first place.

What’s Remembered and What’s Buried

Chicago 1919 showed how fragile progress could be when the state refused justice. A murder on the beach turned into a week-long pogrom because police and politicians sided with white mobs. The Red Summer riots weren’t random. They were part of a campaign of terror meant to keep Black communities in their place. And like so many of these stories, they were buried, downplayed, or twisted into tales of “both sides” at fault.

The federal government couldn’t ignore it completely. The Chicago Commission on Race Relations published The Negro in Chicago in 1922, a landmark report that documented the violence and segregation. It was damning, but like most such reports, it gathered dust while politicians carried on.

What It Left Behind

The scars of 1919 never healed. Today, Chicago is one of the most segregated cities in America, and the gap in income and opportunity between Black and white Chicagoans is no accident. It’s the product of more than a century of racist policy: redlining, housing covenants, school segregation, and deliberate disinvestment. The violence of 1919 wasn’t an aberration, it was a foundation. The press and politicians still find ways to blame Black Chicagoans for the city’s struggles, ignoring that white America built those conditions long before Chicago was even a city.

The lesson? When you hear “race riot,” ask who started it, who died, and who wrote the headlines. Because in 1919, the answer was clear: white mobs killed Black neighbors, the police looked away, and the powerful called it “trouble.” It’s never “both sides.”

Sources

- Chicago Commission on Race Relations, The Negro in Chicago: A Study of Race Relations and a Race Riot (1922)

- Ida B. Wells, contemporary reporting in the Chicago Defender (1919)

- Cameron McWhirter, Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America (2011)

- David F. Krugler, 1919, The Year of Racial Violence: How African Americans Fought Back (2014)

- Elliot M. Rudwick, Race Riot at East St. Louis, July 2, 1917 (for comparative context)

- William M. Tuttle, Jr., Race Riot: Chicago in the Red Summer of 1919 (1970)

- Records of the Illinois National Guard, deployment reports (1919)

- Contemporary coverage in the Chicago Tribune and Chicago Daily News (noting their bias and framing)