The Coal Creek War: 1891-1892

Blood, chains, and rifles in the hills of Tennessee. This wasn’t some minor strike or a local scuffle. It was an armed rebellion that shook the South and smashed a system that looked an awful lot like slavery reborn.

A Nation on Edge

By the 1890s, labor in America was getting hammered. The memory of Haymarket still poisoned unions, with every strike painted as anarchism. Railroad workers had been crushed in 1877, steelworkers at Homestead would be gunned down in 1892, and farmers were rising against banks and railroads. Reconstruction’s promises were dust, replaced by Jim Crow and terror. Capital pulled the strings, the state held the rifles, and working people were left with nothing but guts. And guts don’t pay the rent.

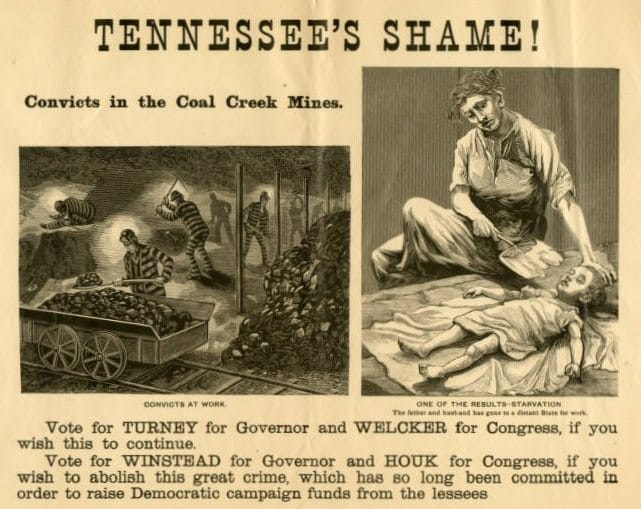

Slavery by Another Name

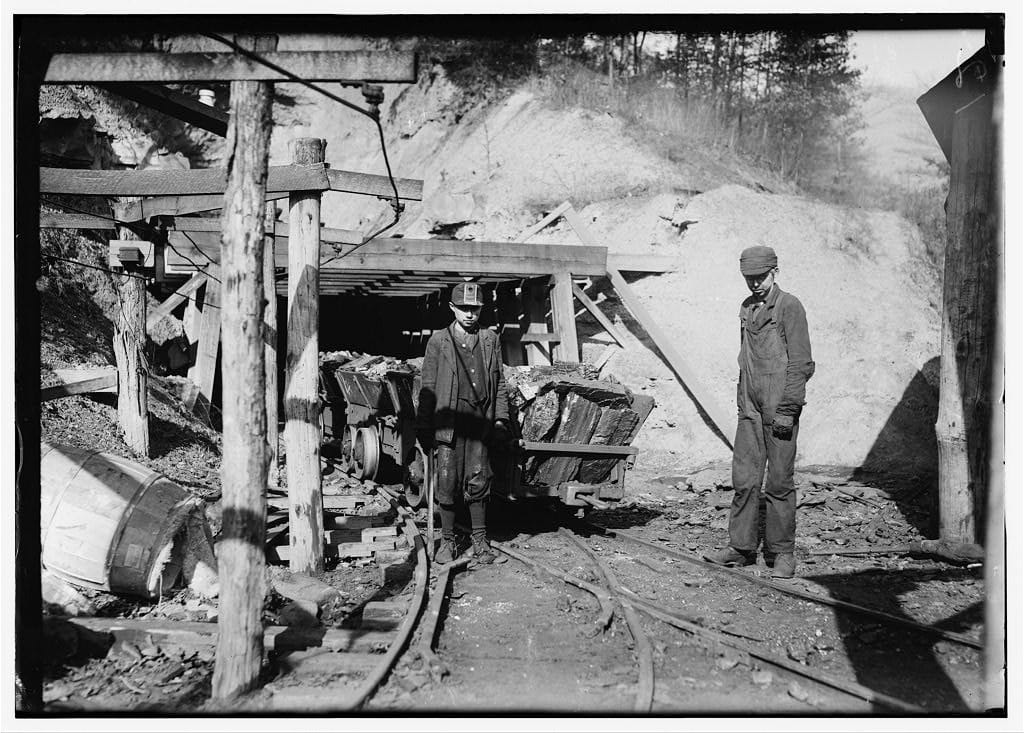

Tennessee’s coal fields were ready to explode. Miners already worked long hours for starvation pay in pits that broke bodies. Then came the convict lease system. The state rented mostly Black prisoners to coal companies, who locked them in stockades and drove them into the mines for nothing.

Most of those men weren’t hardened criminals. They were grabbed on petty or trumped-up charges like vagrancy, loitering, or “insulting” a white man. Judges and sheriffs kept the pipeline full. Prisoners slept on straw in filthy wooden cages. Chained, whipped, and half-starved, they swung picks in choking dust until they dropped. Mortality was staggering: in some camps, one in three convicts died each year. For the companies, a dead man was just a line item. Cheaper to replace a body than repair a mule.

Free miners saw it for what it was. One said convict leasing “made slaves of us all, Black or white, because they broke our wages with slave labor.” For the prisoners, it was slavery reborn, with shotguns instead of auction blocks. Families torn apart. Men vanished into mines and never came back, their names erased in shallow graves.

Lives in Chains

Almost all the convicts were Black, stripped of rights and thrown into a system designed to kill them. Tennessee’s own reports admitted mortality dwarfed that of free miners. A man could be jailed in July and dead by Christmas.

When miners stormed the stockades, they didn’t massacre the prisoners. But they didn’t set them free either. They opened the gates, disarmed guards, and marched convicts onto trains bound for Knoxville. For a few it meant escape. For most it meant another stockade, another mine. The miners weren’t abolitionists. They were defending their own wages. But by refusing to turn their rifles on the convicts, they exposed the horror of the lease system. Messy, limited solidarity—but solidarity all the same.

Opening the Gates

On July 14, 1891, after years of wage cuts and watching chained men marched into their pits, miners in Coal Creek decided enough was enough. They gathered, voted, and acted. If the state would not end convict leasing, they would. The stockades in their backyard weren’t just an insult to wages, they were slavery alive before their eyes. As one miner put it: “They had the state's guns, the state's men, and the state's law. We had nothing but our lives. And they were taking those too.”

Hundreds marched to the Briceville stockade, armed but disciplined. They disarmed the guards, moved the convicts out, and shipped them and the state troops to Knoxville without firing a shot. A week later, they did it again at Oliver Springs. Same result. The message was unmistakable: convict labor would not stand.

The fight spread. All summer, miners tore down stockades, torched company property, and forced the removal of prisoners. On October 31, Halloween night, they raided in costume. Papers called it a carnival of defiance.

The Governor's Betrayal

Governor John P. Buchanan, elected with labor’s support, collapsed under pressure. Instead of siding with miners, he defended convict leasing. He called out the National Guard, who built a fortified camp, Fort Anderson, with Gatling guns and cannons aimed at townsfolk. Skirmishes flared around Coal Creek, Briceville, and Oliver Springs. Blood spilled. The sight of state troops firing on miners burned into memory. This was a governor who rode into office on labor’s back and then stabbed them in it.

The Constitution, Twisted

The Coal Creek War also revealed how the 14th Amendment was gutted in practice. Equal protection on paper meant nothing. Tennessee leaned on the amendment’s loophole allowing involuntary servitude as punishment for crime. Black men were arrested on petty charges, funneled into the lease system, and worked to death. Due process was a joke, protection nonexistent. Free miners saw their wages crushed by the same system. The Constitution promised freedom. Coal Creek showed the betrayal.

Winning by Losing

The fight dragged into 1892, with strikes, raids, and standoffs. By 1893, the system cracked. Tennessee stopped renewing lease contracts, and by 1896 it was dead. Tennessee became one of the first Southern states to kill convict leasing.

Buchanan’s career never recovered. Labor never forgave him. The miners of Coal Creek proved something vital: ordinary workers could defy a system built on chains and profit and force it to crumble. Their motives were mixed, their solidarity imperfect. But they helped destroy a system that should never have existed.

How It Was Spun

They didn’t call it a war by accident. The fight stretched more than a year, with thousands of miners squaring off against state militia behind Gatling guns. Entire towns were caught up. It was organized, sustained, political. Newspapers used the word “war” to dramatize it, and elites wielded it to smear miners as anarchists. Knoxville and Nashville papers obsessed over burned stockades and “lawless mobs,” ignoring the chains on convicts. National coverage echoed the smear. Populist and labor presses told another story, printing miners’ resolutions and pointing out that early raids removed prisoners without bloodshed. The echo wasn’t just gunfire. It was the way the story was twisted, making workers look like criminals. The same playbook is still alive: when people rise, call them anarchists, call them criminals, call them anything but human beings who’ve had enough.

The Coal Creek War was one of the most consequential labor uprisings in U.S. history. It wasn’t just about wages. It was about freedom in the post-Reconstruction South. Convict leasing was slavery dressed up in paperwork, and miners knew it. Their revolt helped end it in Tennessee. Their solidarity was never pure. It was messy, limited, often self-serving. But it mattered. It forced change. And that complexity is the point: history isn’t made by saints. It’s made by flawed people who, for their own reasons, sometimes take a stand that echoes far beyond what they intended.

Sources

- Alex Lichtenstein, Twice the Work of Free Labor: The Political Economy of Convict Labor in the New South(1996).

- Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, “Coal Creek War.”

- Knoxville History Project, “The Coal Creek War.”

- Robert E. Norrell, The Coal Creek Rebellion: Tennessee Miners and the Convict Lease System (1985).

- Libcom pamphlet, The Stockade Stood Burning: Rebellion and the Convict Lease in Tennessee’s Coalfields, 1891–1895.

- Zinn Education Project, “This Day in History: Coal Creek War.”

- Nashville Banner (August 1891), reporting Gov. John P. Buchanan’s “God Almighty himself has drawn the color line” statement.

- Tennessee State Reports on Convict Leasing, 1890–1895 (mortality data).