The Coeur d’Alene Labor Crackdown – 1892

Life in the Silver Valley

In Idaho’s Silver Valley, miners worked ten hours underground for starvation wages. The tunnels dripped with water, dust choked the air, and explosions left men deaf or broken. Families lived in shacks owned by the companies. Pay was cut, rent went up, and miners were treated as disposable.

Among them was Frank Steeves, a union man who spent his evenings organizing his fellow miners. His wife kept food on the table by taking laundry, his children went to school in shoes patched with scraps. They had little, but they had solidarity. And solidarity was the one thing that scared the mine owners.

The Spark

The bosses brought in the Pinkertons. One spy, Charlie Siringo, wormed his way into the union, taking notes and reporting back to management. When the miners discovered the betrayal, rage boiled over. On July 11, 1892, miners stormed the Frisco Mill. Shots rang out, a dynamite blast reduced the concentrator to rubble, and both guards and miners were killed.

The governor declared martial law. The state had chosen its side: capital’s. Call it what it was, naked class war.

The War on Labor

Pinkertons weren’t new to Idaho. They had been strikebreaking across the country, against railroad workers, steelworkers, and soon at Homestead the very same year. Their business was infiltration, betrayal, and violence. The 1890s were a storm: the Panic of 1893 was on the horizon, the Populist movement was rising, and capital and the state were closing ranks. Coeur d’Alene was one front in a national war on labor.

Pinkerton detective Charlie Siringo later bragged in his memoir that he had “completely broken up the Miners’ Union” through spying and deceit. He wasn’t ashamed. He built his reputation on it. Siringo had chased Billy the Kid, infiltrated outlaw gangs, and later boasted of his exploits in dime-novel style books. But his most lasting mark was as a Judas in the labor wars, selling out working families for a paycheck and then turning betrayal into self-promotion. The press treated him like a folk hero, but the miners knew him for what he was: a traitor whose lies helped get men killed.

The Bullpens

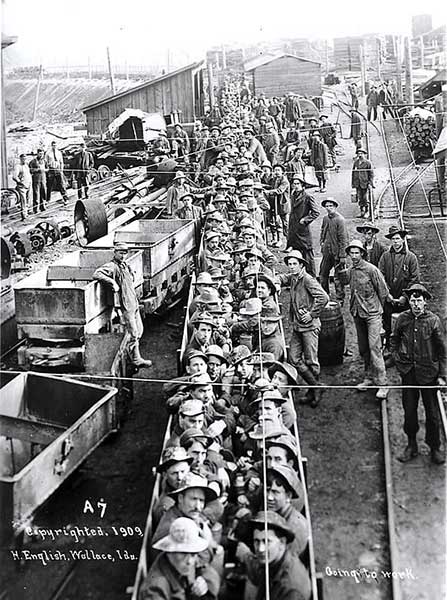

Governor Norman Willey declared martial law, and he called in the Idaho National Guard while also requesting federal troops. President Benjamin Harrison approved, and soldiers from Fort Sherman and Fort Spokane marched into the Silver Valley. In total, about 1,500 men locked the region down.

Hundreds of miners, guilty and innocent alike, were rounded up. They weren’t given trials. They weren’t even given charges. Instead, they were herded into barbed-wire stockades the authorities called “bullpens.”

Men slept in mud, packed shoulder to shoulder. They lived on scraps. Disease spread, and contemporary accounts recorded deaths from disease and neglect inside, even though no official records were kept. Wives and children stood outside the fences, powerless to help their husbands and fathers. These were concentration camps before America used the word.

Contemporary papers confirmed the conditions. The Idaho Statesman described the prisoners as “herded like cattle in a corral, guarded day and night by soldiers.” The Spokane Review noted that many were held “without the formality of charges, a clear warning to all workingmen who would defy capital.” One imprisoned miner later recalled in union testimony that it was “a prison without walls, where men wasted away.” Meanwhile, the New York Times dismissed the prisoners as “rioters and lawless men who brought ruin upon themselves,” and the Spokane Chronicle praised the roundup as a way to “teach these agitators the lesson they need.”

Siringo bragged in his memoir that he had broken the strike, as if betrayal was something to be proud of.

Aftermath

The strike was crushed. Union men were blacklisted across the valley. Some fled, others bent their backs under worse terms than before. The state and mine owners congratulated themselves on restoring “order.”

For the miners and their families, “order” meant hunger, eviction, and silence. It was bullshit dressed up as peace.

Frank Steeves was among those dragged into the bullpens. When he finally got out, the companies blacklisted him. He couldn’t get hired in the mines again. His family paid the price in hunger and exile, a reminder that “order” didn’t just mean smashed unions, it meant shattered lives.

Legacy

The Coeur d’Alene crackdown wasn’t a unique plan but another chapter in a long tradition: detention without charges, martial law declared on flimsy pretexts, and the rights of working people trampled when they threatened profit. In 1892 it was union miners penned in the mud. In 2025 it’s immigrants crammed into detention centers, held without trial in overcrowded cages. Different century, same contempt for human dignity. The uniforms and excuses change, the cages stay the same.

Siringo’s Turn

Even Siringo, who sold out miners here, later soured on the Pinkertons. He tried to publish exposés about their corruption, but the agency dragged him into court and buried his words. Yet he never changed his view of labor. In his book draft Two Evil Isms: Pinkertonism and Anarchism, he lumped unions and anarchists together as a menace. A man who once bragged about betrayal ended his days trying, and failing, to warn the world about the monster he had served, all while still damning the very workers he had helped destroy.

#RiotADay #LaborHistory #USHistory #History 🗃️

Sources

- Idaho Statesman (1892), contemporary reporting on the bullpens.

- Spokane Review (1892), coverage of mass detentions.

- New York Times (1892), hostile coverage portraying miners as rioters.

- Spokane Chronicle (1892), editorial support for the crackdown.

- Charlie Siringo, A Cowboy Detective (1912), memoir bragging about union infiltration.

- Charlie Siringo, Two Evil Isms: Pinkertonism and Anarchism (1915, unpublished manuscript fragments, portions held in the University of Texas and New Mexico State Records Center archives), reflecting both his disillusion with the agency and his hostility to labor.

- Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Vol. 2 (1947), context on the Coeur d’Alene strike.

- Elizabeth Jameson, All That Glitters: Class, Conflict, and Community in Cripple Creek (1998), comparative analysis of mining labor wars.

- Ross Rieder, “The Coeur d’Alene Labor Wars,” Pacific Northwest Labor History Association archives, including recollections from imprisoned miners about the bullpens.