The Cripple Creek Strike: 1894

Today’s post looks back at Cripple Creek in 1894, when miners faced down the bosses and, for once, actually won. Right now, federal troops are being moved into American cities, not to protect people but to push an agenda of control. Cripple Creek shows what it looks like when government takes the other side, when it stands with its people instead of turning rifles on them.

A Line in the Dust

The Panic of 1893 hit like a hammer. It was the worst depression in American history until the Great Depression. Jobs vanished, wages collapsed, and everywhere the bosses clawed back the little ground workers had won. In the gold mines of Cripple Creek, Colorado, owners tried to steal back two hours of every man’s life. The 8 hour day was cut back to 10, and if the miners didn’t like it, they could choke on dust and cave ins until they broke.

For once, the miners said no. In February 1894, over 3,000 of them walked out. They were neighbors and fathers, many of them immigrants, bound together in the brand new Western Federation of Miners. Among them was Ed Boyce, an Irish immigrant who would rise to lead the WFM in the years ahead, and John Calderwood, who would become president of the union during the strike. Their demand wasn’t wild or radical. It was simple: give us back the 8 hour day. Calderwood had even kept his own Anchoria-Leland mine on an 8 hour schedule, standing apart from the big owners who wanted to grind men down. Families ran strike kitchens, kids carried messages through the hills, and women organized support, making it a community fight, not just a union one.

Deputies and Dynamite

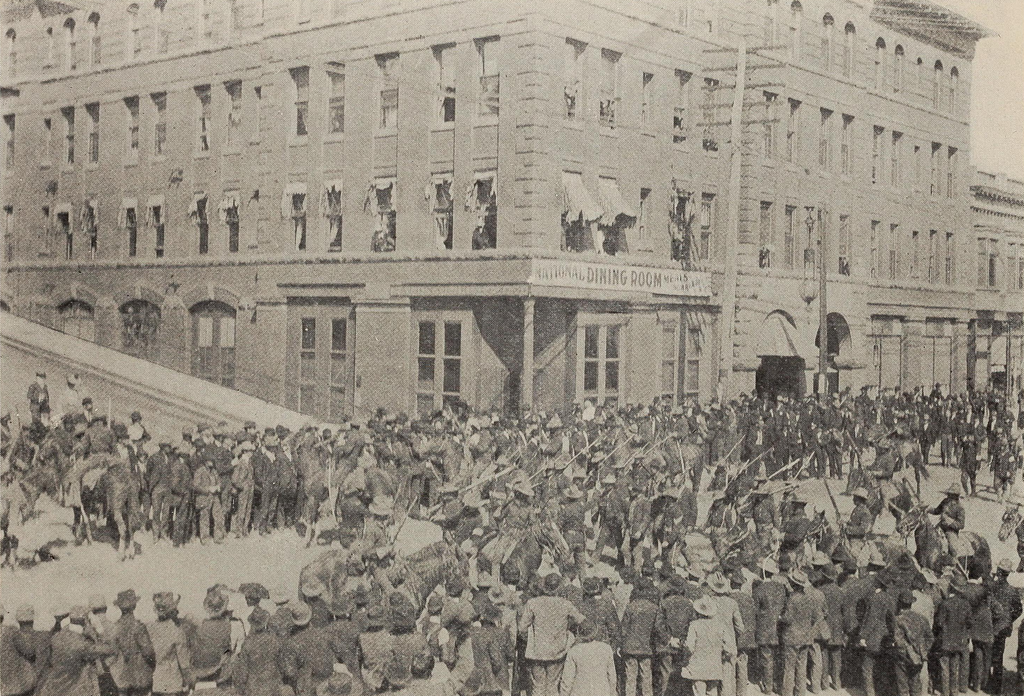

The mine owners answered the way they always did. They banded together in the Mine Owners’ Association, a cartel determined to break the union and claw back hours. They poured money into El Paso County Sheriff M.F. Bowers, who deputized hundreds of drifters and thugs to act as a private army. Camps were raided, strikers beaten, families terrorized. The usual American playbook.

But the miners weren’t rolling over. They took to the hills, armed themselves, and when scabs tried to tunnel into mines at Altman and Strong, the strikers used dynamite to shut them down. Explosions echoed across the district, shocking the state and grabbing national headlines. That got everyone’s attention.

The Governor Stands Up

In almost every labor fight of the era, this is the moment the state showed up with rifles pointed at the workers. But in Colorado, the governor was Davis Waite. Waite was no friend of capital. A Civil War veteran who had edited the union newspaper Union Era in Aspen, he rode the Populist wave of the 1890s into office with the backing of farmers and miners. He was called cranky, stubborn, and worse by the mine owners, but he was loyal to the people who elected him.

When the Mine Owners’ Association raised a private army of deputies, Waite sent in the state militia - not to crush the strike, but to rein in the bosses. His soldiers disarmed the deputies and stood between armed capital and the men in the pits. This had never happened before in a major American strike. Contemporary accounts even noted that the militia behaved with restraint and fairness, a shocking contrast to the thuggery of Bowers’ deputies. For once, the state didn’t massacre working people. It protected them.

A Rare Victory

By June the mine owners caved. The 8 hour day was restored. The strike ended in a clear win for the Western Federation of Miners, one of the only real labor victories of the 19th century. The WFM came out stronger, and Cripple Creek became the birthplace of its reputation for militancy. Solidarity, backed by a governor with a spine, had forced the bosses to blink.

Why It Matters

Cripple Creek was the exception, not the rule. Within a decade, the WFM would face bloodbaths at Leadville, Telluride, and Ludlow. The pattern snapped back hard: private armies, state violence, workers cut down. But in 1894, for one brief season, the rifles weren’t turned on the miners.

That is what makes Cripple Creek different. In a century littered with massacres, here was a strike where the people fought back, the governor stood with them, and the miners actually won.

Sources

- Benjamin McKie Rastall, The Labor History of the Cripple Creek District (1908)

- Emma F. Langdon (ed.), The Cripple Creek Strike: A History of Industrial Wars in Colorado (1905)

- Elizabeth Jameson, All That Glitters: Class, Conflict, and Community in Cripple Creek (1998)

- Colorado Encyclopedia, “Western Federation of Miners”

- AFL-CIO, “The Battle of Cripple Creek”

- Contemporary press and accounts via Denver Public Library and Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum