The East St. Louis Massacre, 1917

Not a riot. A pogrom.

The state said 39 dead. The NAACP said closer to 200. Survivors swore it was worse. The truth was buried because admitting the scale meant admitting guilt. This wasn’t some accident of history, it was murder dressed up as order. East St. Louis in July 1917 was not chaos, it was a pogrom stoked by racist cries of a so-called "Black invasion," carried out while the city looked on.

The Context

The United States was mobilizing for World War I. Factories ran day and night on government contracts. White unions barred Black workers, so bosses recruited thousands from the South during the Great Migration. Local papers warned of an “invasion” of Black laborers. White labor leaders in East St. Louis marched demanding that Black workers be expelled. Instead of solidarity, unions chose to scapegoat their fellow workers.

By May and June, smaller attacks and harassment of Black workers were already breaking out. On July 1, a car of white men drove through a Black neighborhood firing shots. That night, Black residents, fearing another assault, fired on a different car and killed two plainclothes police. The next day, July 2, the violence exploded into a full-scale pogrom. White mobs poured into the streets, burning homes, lynching neighbors, and driving thousands from the city.

The Pogrom

White mobs stalked their neighbors. They dragged Black men off streetcars, beat them to death, and left their bodies in the gutter. Elijah Hicks stepped onto his porch to see what the shouting was about. He was shot before he said a word. Charles Turner was trapped in his home and burned alive while neighbors listened to his screams. Families fleeing across the bridge were ambushed, shot, or clubbed to death. Mothers carrying infants were chased into the Mississippi River. Imagine seeing the woman who brought bread from her kitchen yesterday running with her children through smoke, or watching a cousin gunned down in the street. The horror wasn’t distant. It was friends, family, and neighbors destroyed by the people they had lived and worked beside.

The Illinois National Guard was sent in. Survivors later testified that Guardsmen fired into fleeing crowds or stood by while mobs torched homes. The state didn’t stop the killing. It joined it.

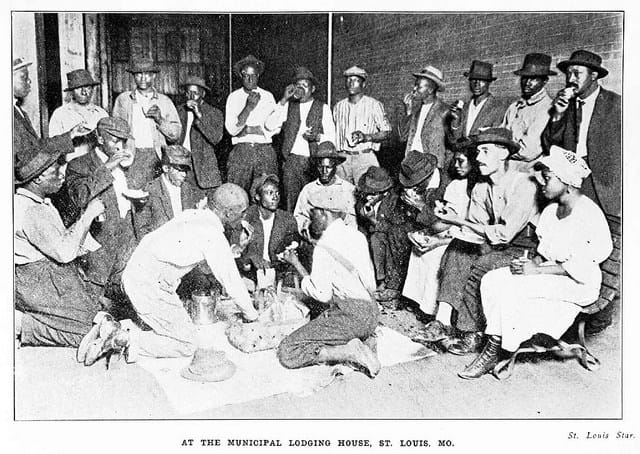

By the end, whole blocks of East St. Louis’s Black community lay in ashes. Six thousand people were left homeless, huddling in makeshift camps. Entire neighborhoods erased. Businesses gone. Generational wealth destroyed in a weekend.

The People Who Lived It

Martha Mitchell told Congress how she hid while her neighborhood was set ablaze, watching neighbors cut down in the street. Ida B. Wells collected testimony from mothers who carried babies through fire and smoke while mobs hunted them down. Survivors described Guardsmen mocking them, calling them “black devils,” before pulling triggers. These stories did not come from statistics or dry reports, but from human beings forced to recount how their families were terrorized and their homes destroyed.

These weren’t “rioters.” They were families, neighbors, and workers trying to live their lives, turned into refugees overnight.

The Aftermath

East St. Louis was a national scandal. President Woodrow Wilson was preaching democracy abroad while ignoring mass murder at home. Illinois Governor Frederick Gardner and Mayor Fred Mollman looked the other way while people were slaughtered in the streets. Nobody in power paid a price.

A federal House committee held hearings. Survivors traveled to Washington and testified in detail about murders, arson, and Guard complicity. Congress listened, then did nothing. The ritual of “investigation” was cover for inaction.

The Black press refused to let it go. The Crisis and the Chicago Defender ran searing accounts. W.E.B. Du Bois wrote that democracy abroad was a sham while pogroms raged at home. James Weldon Johnson of the NAACP called East St. Louis “an orgy of brutality.” The outrage helped spark the NAACP’s Silent Parade in New York City. Ten thousand Black men, women, and children marched down Fifth Avenue in silence. No chants. No speeches. Just banners: “Thou shalt not kill.” “Mother, do lynchers go to heaven?”

The Story We Carry

Again, this was not a riot. It was a massacre, a pogrom carried out with the blessing of local officials and the complicity of the Guard. Black workers were cast as scapegoats, lies were spread, and mobs did the dirty work of bosses and politicians.

And like so many of the massacres in this project, it was powered by a moral panic. Fear of newcomers weaponized into rage, unions turning their backs, politicians letting terror do their work. A community was destroyed not because of what its people did, but because fear was profitable and convenient. Almost every atrocity we’ve covered carries the same fingerprints: invent a threat, whip up panic, and unleash violence on the scapegoat of the day.

Remember the names we know: Elijah Hicks, Charles Turner, and Martha Mitchell who testified. And remember the hundreds more whose names were buried or forgotten. They weren’t faceless victims of “race trouble.” They were families and neighbors turned into corpses and refugees while the state looked away. And the shadow of that fear lingered. For years, East St. Louis stood as a warning to Black families moving north: even here, in the industrial heartland, you could be murdered for daring to work and live.

Sources

- NAACP, The Massacre at East St. Louis (1917)

- Congressional Record, House Committee on Rules hearings, 1917

- Ida B. Wells, collected testimonies in The Crisis

- James Weldon Johnson, NAACP field report, 1917

- W.E.B. Du Bois, writings in The Crisis, 1917

- Harper Barnes, Never Been a Time: The 1917 Race Riot That Sparked the Civil Rights Movement (2008)

- Elliott Rudwick, Race Riot at East St. Louis, July 2, 1917 (1964)