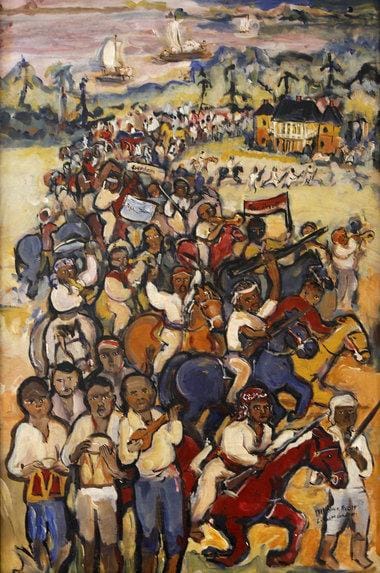

The German Coast Uprising, 1811

America's largest slave rebellion has been mostly erased from our collective memory. Five hundred people marched for freedom through the Louisiana rain, chanting as they went. They were hunted down like animals, tortured, executed, and beheaded. Their heads were mounted on pikes for forty miles along River Road as a warning to anyone else who dared dream of liberty.

This wasn't Nat Turner's rebellion. This happened twenty years earlier, and it was ten times larger. But because Louisiana was still a frontier territory in 1811, because acknowledging it would shatter the myth of the contented slave, and because the victors always write the history, the German Coast Uprising was deliberately buried and forgotten.

Haiti's Shadow Falls on Louisiana

To understand why this happened, you need to understand what terrified white planters across the South: Haiti. Just seven years earlier, in 1804, enslaved people in Saint-Domingue had done the impossible. They'd defeated Napoleon's armies, overthrown their masters, and created the first Black republic in the Western Hemisphere. The Haitian Revolution sent shockwaves through every slaveholding society in the Americas.

Louisiana's sugar country was ground zero for that fear. After Haiti's revolution, thousands of French planters fled to Louisiana with their enslaved workers, bringing both sugar expertise and fresh memories of what happened when enslaved people rose up. By 1811, Louisiana's German Coast - a stretch of fertile land along the Mississippi River named for the Germans who'd settled there in the 1720s - had become one of the richest sugar-producing regions in North America. That wealth was built entirely on enslaved labor.

The conditions were brutal beyond measure. Sugar cultivation was the deadliest form of slavery in North America. Enslaved people worked eighteen-hour days during harvest, processing cane in mills where one wrong move could mean losing a hand or arm. The heat, the backbreaking labor, and the constant threat of violence meant enslaved people on sugar plantations had the shortest life expectancies in the slave South. Many of those laboring in Louisiana had been born in Africa or the Caribbean and knew that resistance was possible. They'd heard the stories from Haiti. They knew revolution could succeed.

The Storm Breaks

On the cold, rainy night of January 8, 1811, Charles Deslondes led a small group of enslaved men into the mansion of Manuel Andry. Deslondes was a mixed-race driver - an overseer of other enslaved people - which gave him mobility and access across plantations. He'd spent months organizing, meeting secretly with men like Quamana and Harry to plan the uprising. They'd chosen their moment carefully: the sugar harvest was over, work had relaxed, and everyone's guard was down.

The rebels struck Andry with an axe, wounding him badly, and killed Baptiste Thomassin, a free man of color who served as overseer. They ransacked the plantation looking for weapons and militia uniforms stored there. Then they did something remarkable: they put on those uniforms, formed military ranks, and marched downriver toward New Orleans beating drums and carrying flags. This wasn't a chaotic mob. It was an army.

As they moved from plantation to plantation along the east bank of the Mississippi, their numbers swelled. Some joined willingly. Others were forced - not everyone wanted to risk everything, knowing what would happen if they failed. By the time they reached St. Charles Parish, between 200 and 500 people marched together. They burned plantation houses, destroyed crops, and killed Jean François Trépagnier, a white planter who tried to stop them. Their goal was nothing less than taking New Orleans itself, capturing the arsenal at Fort St. Charles, and freeing thousands more enslaved people in the city.

They marched for two days, covering nearly thirty miles before white panic finally organized into violence.

The Slaughter

Manuel Andry, despite his wounds, had escaped across the Mississippi River and raised the alarm. By January 10, planters had formed militias and federal troops arrived from New Orleans. Governor William Claiborne declared martial law. What followed wasn't a battle - it was a massacre.

On January 11, militia forces led by the wounded Andry himself, along with General Wade Hampton and federal troops, attacked the main body of rebels at Bernard Bernoudy's plantation. The rebels, armed mostly with cane knives, hoes, and axes, stood little chance against muskets and organized firepower. About forty were killed in the fighting. Many more fled into the swamps.

What came next was terror as policy. Militias hunted the survivors through marshes and woods using dogs and Native American trackers. They killed fourteen more in skirmishes. They captured dozens, held quick tribunals, and executed at least eighteen more at the Destrehan Plantation.

Charles Deslondes was among the first caught. The militia didn't bother with a trial. Naval officer Samuel Hambleton described what they did: "Charles had his hands chopped off then shot in one thigh & then the other, until they were both broken - then shot in the body and before he had expired was put into a bundle of straw and roasted!" His screams were meant to intimidate anyone hiding in the marshes. It worked.

Others faced similar fates. Quamana, Harry, Kook - leaders and participants alike - were executed and decapitated. Their heads, along with dozens of others, were mounted on pikes and displayed for forty miles along River Road from New Orleans deep into plantation country. The message was unmistakable: this is what happens when you reach for freedom.

By the time the killing stopped, close to 100 enslaved people were dead. Only two white men had been killed in the entire uprising.

The Erasure

White authorities didn't just crush the rebellion - they tried to erase it from history. Newspapers minimized the numbers, calling it a minor disturbance. Officials sealed records. The story was buried, overshadowed twenty years later by Nat Turner's rebellion in Virginia, which killed more white people and thus received more coverage and panic.

For generations, the German Coast Uprising was forgotten, a footnote if it was mentioned at all. Slaveholders couldn't allow the story to spread. It undermined everything they claimed about slavery - that enslaved people were content, childlike, incapable of organized resistance. Five hundred people marching in military formation, demanding liberation, proved all of that was a lie.

The men and women of 1811 weren't just fighting for themselves. They were fighting for everyone who came after. Their children and grandchildren would finish what they started: 28,000 Black Louisianans - more than from any other state - fought for the Union Army in the Civil War.

Charles Deslondes, Quamana, Harry, Kook, and the hundreds who marched with them knew they might die. They marched anyway. They proved that enslaved people had political consciousness, military strategy, and revolutionary will. They proved that the only thing slavery required to fail was for people to refuse to accept it.

No one who led the massacre faced consequences. Manuel Andry recovered from his wounds and continued to profit from slavery. The militiamen went home. The federal government moved on. Justice, as always, was reserved for the victors.

But the rebels of 1811 aren't forgotten anymore. The Whitney Plantation, the first plantation museum in America dedicated to the enslaved experience, memorializes their sacrifice. Descendants still gather at Norco every January to honor them. Their story has been reclaimed, their courage remembered, and their names spoken again.

They were not beasts. They were not property. They were people who chose freedom, knowing the cost. And they changed history.

Sources

- Daniel Rasmussen, American Uprising: The Untold Story of America's Largest Slave Revolt (Harper Perennial, 2011)

- Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, Louisiana Slave Database

- Leon A. Waters, "Jan. 8, 1811: Louisiana's Heroic Slave Revolt," Zinn Education Project

- Robert L. Paquette, "'A Horde of Brigands?': The Great Louisiana Slave Revolt of 1811 Reconsidered," Historical Reflections/Réflexions Historiques 35 (Spring 2009)

- Original trial records, New Orleans City Court cases #184-195, City Archives

- Contemporary letters from Manuel Andry and General Wade Hampton, January 1811