The Greensboro Massacre, 1979

The 1979 Greensboro Massacre is what happens when the cops know an ambush is coming, know there are guns, know exactly when and where - and just don't show up. Five labor organizers gunned down in broad daylight by a caravan of Klansmen and Nazis. TV cameras rolling. Witnesses everywhere. All-white juries acquitted the shooters twice. The police informant who helped plan it walked free. America's idea of justice.

What They Were Organizing Against

This wasn't random violence. It came from something specific: organizing Black and white textile workers together in North Carolina's mills. In the late 1970s, members of the Workers Viewpoint Organization (soon renamed the Communist Workers Party) had traction. Real traction.

Dr. Jim Waller, who grew up in a Jewish household in Chicago, got his medical degree from the University of Chicago. In 1973, he set up a clinic at Wounded Knee to provide medical care to American Indian Movement activists under siege by the FBI. He came to North Carolina and worked with the Carolina Brown Lung Association, screening textile workers for the lung disease that was killing them. Then in 1976, he walked away from medicine entirely and became a floor worker at Cone Mills' Granite Finishing Plant. He became president of the textile workers union. When Cone fired him - claiming he failed to list his medical training on his job application, obvious retaliation - workers launched a 12-day wildcat strike. Waller was elected president of Local 1113T. He and his wife Signe printed union newsletters on a mimeograph machine at home.

Sandi Smith was born on Christmas Day, 1950, in South Carolina. At 21, she was student body president at Bennett College and a founding member of the Student Organization for Black Unity. She trained as a nurse but postponed finishing to organize. She got herself hired at Cone's Revolution Plant specifically to organize from the inside. She co-founded the Revolution Organizing Committee, filed grievances with the NLRB, got OSHA to inspect the mill for the first time in its history. She led a march of 3,000 people in Raleigh to free the Wilmington 10.

Bill Sampson graduated from Harvard Divinity School and was in medical school. He was a shop steward and president-elect of his union local at Cone's White Oak Plant, leading the fight for worker health and safety.

Cesar Cauce came to the U.S. as a child, a Cuban refugee. He grew up in Miami, graduated magna cum laude from Duke, and organized hospital workers at Duke Medical Center.

Michael Nathan was chief pediatrician at Lincoln Community Health Center in Durham, serving low-income families. He organized medical supplies for liberation fighters in Zimbabwe. He wasn't even a CWP member - he was there supporting his wife Marty, who was.

They were winning. Black workers who'd only recently been allowed into textile jobs thanks to the 1972 Equal Employment Opportunities Act were joining up alongside white workers. The kind of multiracial organizing that terrifies power.

The Klan noticed. So did the Nazis. And apparently, so did the cops and the feds. Because... well, that's how that goes.

The Setup

On July 8, 1979, CWP members disrupted a Klan screening of Birth of a Nation in China Grove, North Carolina. They burned a Confederate flag, taunted armed Klansmen standing on the town hall steps. Local cops made the Klan go back inside. The organizers considered it a victory and planned a bigger anti-Klan march in Greensboro for November 3.

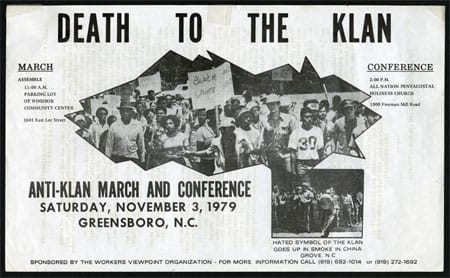

They called it the "Death to the Klan March." Which is fucking fantastic. The flyers made clear what it was about: organizing against racism and the divisions the Klan used to keep workers from uniting. The march was scheduled to start at Morningside Homes, a predominantly Black housing project, then proceed to a community center for a conference.

The Communist Workers Party applied for a permit. The Greensboro Police Department granted it - with one condition: no weapons. The marchers had to be unarmed. The permit also listed the unpublished starting location. The cops handed their informant Eddie Dawson - a Klan member - the permit with the exact location. Dawson did exactly what you'd expect: he told his Klan buddies where to find the marchers.

The morning of November 3, Dawson told police the Klan was armed and ready for violence. A nine-car caravan loaded with guns was heading to Morningside Homes. The police knew. The feds knew too - ATF agent Bernard Butkovich had been embedded with the Nazis for three months. He knew they were coming armed. He didn't tell anyone who might stop it.

The tactical squad assigned to monitor the march? Suspiciously absent when the caravan rolled up at 11:23 a.m. - 37 minutes before the march was scheduled to start.

88 Seconds

Around 150 people had gathered at Morningside Homes. The Klan and Nazi caravan pulled in. Words were exchanged. Some demonstrators kicked the cars, struck them with sticks. Then the Klansmen and Nazis grabbed rifles, shotguns, and pistols from their vehicles and opened fire.

The CWP members had a few concealed weapons and returned fire. It didn't matter. The attackers had come prepared for a slaughter.

When the shooting started, Sandi Smith was looking after children. She ran forward to help them when the gunfire erupted. Someone slammed her on the head with a stick. Her comrades dragged her to safety behind a building. She poked her head out to make sure the children had gotten to safety. Shot between the eyes. She was 28 years old.

Jim Waller ran for cover. Shot in the back, the bullet piercing his heart and lungs.

Cesar Cauce was knocked down with a picket stick, then shot through the back of his neck.

Bill Sampson returned fire with a handgun. Shot in the heart. As he lay dying, he handed his gun to another organizer who was already wounded.

Michael Nathan stood in the intersection. Shot twice in the head. He died two days later in the hospital. His wife Marty survived her wounds.

Ten others were wounded, including Paul Bermanzohn, who took a bullet to the brain. He survived but lived with permanent paralysis on his left side. Television cameras caught it all. The whole massacre, start to finish, on tape. The police arrived after it was over.

The Trials, The Verdicts, The Nothing

In 1980, six Klansmen and Nazis stood trial for first-degree murder. All-white jury. Acquitted. The defense claimed self-defense. Never mind that they'd driven to the site armed and ready, that a police informant had helped them plan it, that the cops had conveniently vanished.

In 1984, a federal trial on civil rights charges. Nine defendants. All-white jury. Acquitted again.

In 1985, survivors filed a civil suit seeking $48 million in damages. They alleged - correctly - that law enforcement knew violence was coming and did nothing. The jury found some defendants liable, but only for the wrongful death of Michael Nathan. The city paid his widow $351,500. The families of Waller, Cauce, Sampson, and Smith got nothing.

Eddie Dawson, the police informant who orchestrated the attack? Never charged. Bernard Butkovich, the ATF agent who knew it was coming? Never charged. The cops who weren't there? Never disciplined.

What Came After

The massacre worked. It chilled anti-racist and labor organizing across the South and beyond. The CWP dissolved. The survivors scattered, went into other work, tried to rebuild. The city of Greensboro spent decades refusing to even call it a massacre. Some council members preferred "shootout," as if both sides had equal blame.

In 2004, survivors and community members formed a Truth and Reconciliation Commission - modeled after South Africa's post-apartheid process - to investigate what happened. The commission had no subpoena power, no ability to compel testimony, but it issued a report in 2006: the Klan and Nazis intended violence, and the police bore significant responsibility for letting it happen.

In 2009, the city council passed a resolution expressing "regret." Not an apology. Regret. In 2015, after fierce debate, they unveiled a historical marker. Two council members voted against it because they didn't think the word "massacre" was appropriate. In 2020 - 41 years later - the city finally apologized.

It took four decades for Greensboro to admit what everyone already knew: the cops let it happen. The state chose not to protect five people whose only crime was organizing workers and challenging white supremacy.

That's the lesson. Not that violence came - violence always comes for organizers. The lesson is that the state knew, the state watched, and the state let the killers walk.

Sources:

- Greensboro Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Final Report (2006)

- Elizabeth Wheaton, Codename GREENKIL: The 1979 Greensboro Killings (1987)

- Sally Bermanzohn, Through Survivors' Eyes: From the Sixties to the Greensboro Massacre (2003)

- Signe Waller, Love and Revolution: A Political Memoir (2002)

- Aran Shetterly, Morningside: The 1979 Greensboro Massacre and the Struggle for an American City's Soul (2024)