The Haymarket Affair: May 4, 1886

A Story Half Remembered

Some of the stories in this project you’ve likely never heard. This one you probably have, but chances are you haven’t heard the whole of it. The Haymarket Affair is one of the most infamous episodes in American labor history, and no reckoning with strikes and repression would be complete without it.

The Storm of 1886

In the spring of 1886, the demand for the eight-hour day swept across the United States. More than 300,000 workers went on strike nationwide. Chicago was the epicenter. Tens of thousands filled its streets on May 1 (Mayday), demanding time for life outside the factory. The city’s industrial barons and political elite seethed. The press called the strikers “foreign savages” and “rabid anarchists,” whipping up fear of immigrants and radicals.

On May 3, at the McCormick Reaper Works on the Southwest Side of Chicago, police opened fire on striking workers. At least two, perhaps six, were killed. Their blood was still wet on the cobblestones when labor leaders called for a protest the next day in Haymarket Square.

The Rally

The evening of May 4 was damp and cool. Rain hung in the air, and the crowd that had been thousands fell to a few hundred. Families stood under umbrellas. The speeches were winding down. Around 10 p.m., Samuel Fielden finished at the wagon.

Then the police came.

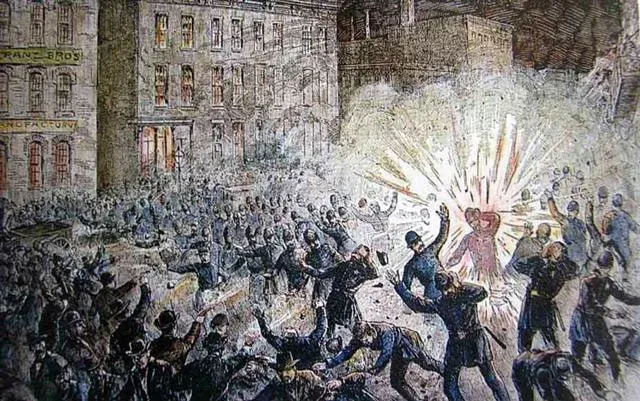

Nearly two hundred officers marched in ranks toward the wagon. They ordered the meeting to disperse. They kept coming.

A small, smoking object arced out of the darkness and dropped among the front line. The blast tore through the formation, killing one officer instantly and mortally wounding others. Panic. Gunfire. Police shot into the retreating crowd. Workers, families, and bystanders went down. Dozens were hit. Some died where they fell, their names never recorded.

Rumors spread fast. Was it a lone anarchist, or a police agent sent to light the fuse? Workers at the time believed it was a setup. August Spies wrote, “Who threw that bomb? I do not know. But I know this: the working class has been shot down again.” Years later Governor John Peter Altgeld would say, “The evidence does not show that any of the defendants had any part in the throwing of the bomb; it does not show that they knew who did throw it.” Historians still argue. Paul Avrich wrote, “We will never know who threw the bomb at Haymarket… but it gave the authorities the opportunity to destroy the anarchist movement.” James Green called it “the pretext for a national campaign to paint the eight-hour movement as a foreign conspiracy.”

The bomber was never found. The city chose its targets anyway.

The Eight Men

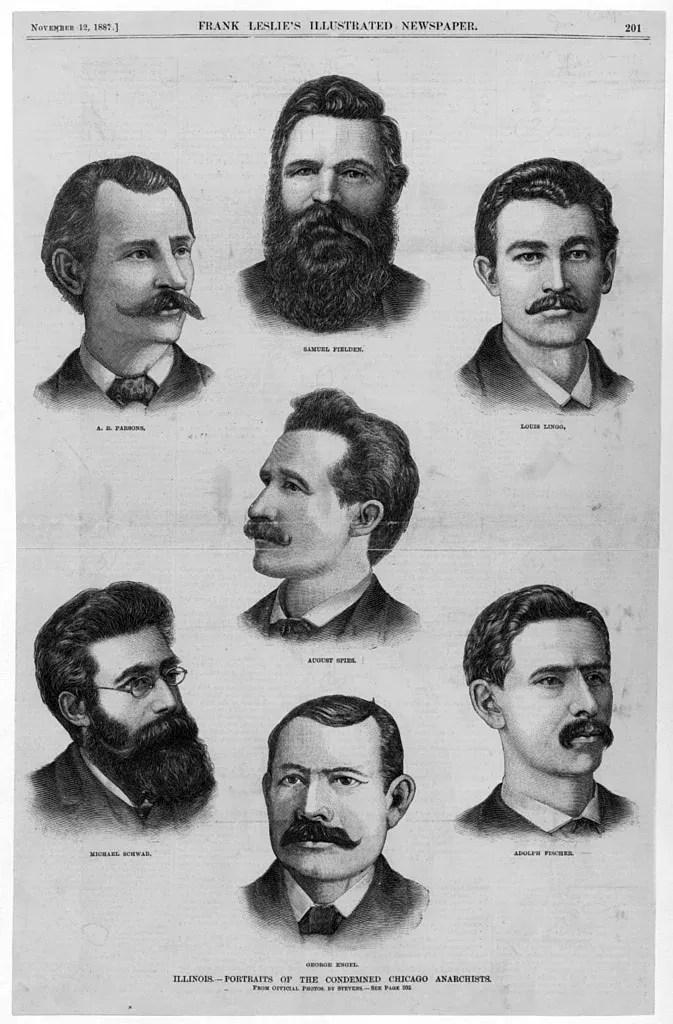

The bomber was never identified. Instead, the city turned on its most visible radicals. Eight men were arrested, not for throwing the bomb, but for who they were and what they believed. They were labor leaders, immigrants, printers, carpenters, editors, fathers.

- August Spies, German-born editor of the Arbeiter-Zeitung, who had seen police kill workers with his own eyes.

- Albert Parsons, a printer from Texas, Civil War veteran, married to Lucy Parsons, herself a fearless labor organizer.

- Samuel Fielden, an English-born preacher and teamster who had spoken that night.

- George Engel, a German immigrant and furniture worker.

- Adolph Fischer, a German immigrant and journalist.

- Michael Schwab, a typesetter and union man.

- Louis Lingg, a 21-year-old German carpenter, fiery and uncompromising.

- Oscar Neebe, an American-born salesman who supported the cause.

They were tried not for what they had done, but for what they believed and said. As the prosecutor told the jury: “Anarchy is on trial.”

The Trial and the Gallows

The trial was a sham. No evidence tied any of the eight men to the bomb. Yet seven were sentenced to hang, one to prison. Louis Lingg defied them to the end. On the night of November 10, 1887, he smuggled a small dynamite cartridge into his cell. He put it in his mouth, lit it with a cigar, and it exploded, blowing off half his face. Lingg lingered alive for hours, writhing in agony, but he had denied the state the chance to stage his execution. His last cry was reported as, “Hoch die Anarchie!”, long live anarchy. The others faced the gallows on November 11, 1887.

August Spies declared: “The time will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today.”Albert Parsons refused a blindfold: “Let the people see how you treat their friends.” Engel and Fischer died alongside them. Fielden and Schwab had their sentences commuted to life in prison, and Neebe was sentenced to fifteen years. They remained behind bars long after the gallows had been cleared.

The Pardon

Six years later, in 1893, Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld pardoned the three survivors. His pardon became part of the legacy of Haymarket. It was the state itself admitting the men had been railroaded. It ended his political career, but it gave future generations of workers proof that their cause had been slandered, and that truth could not be buried forever.

The Legacy

The Haymarket Affair became a symbol across the world. May Day, International Workers’ Day, traces its origins to those men and that night. In the United States, the story was buried under law-and-order propaganda, taught as a cautionary tale of “riots” rather than remembered as the killing and railroading of working men. But their words echo still. And their silence has proved powerful.

Albert Parsons died on the gallows, but Lucy Parsons carried his name and their cause for half a century. She spoke to crowds of thousands, was banned from her own city, and was called by police “more dangerous than a thousand rioters.” She helped found the Industrial Workers of the World and kept Haymarket’s fire alive until her death in 1942. Through her, the movement refused to be silenced.

The script has not changed. In 1886, the press and the city rushed to blame the radicals they already feared, with no evidence. Today the same playbook is used, slapping the word “Antifa” on any protest that threatens power. Haymarket shows how scapegoats are chosen first, and facts come later, if ever.

#RiotADay #LaborHistory #USHistory #History 🗃️

Sources

- Paul Avrich, The Haymarket Tragedy (Princeton University Press, 1984)

- James Green, Death in the Haymarket (Pantheon, 2006)

- Timothy Messer-Kruse, The Trial of the Haymarket Anarchists (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011)

- Encyclopedia of Chicago, "Haymarket Affair" (Chicago Historical Society)

- Illinois Labor History Society, "The Haymarket Affair" resources

- Chicago History Museum, Haymarket Digital Collection

- Governor John Peter Altgeld, Pardon Statement, June 26, 1893

- Contemporary coverage, Chicago Tribune, May 1886

- Lucy Parsons Project, biographical archives and collected writings

- Industrial Workers of the World, founding records and speeches

- EBSCO Research Starters, "Haymarket Square, Chicago"

- PBS American Experience, "The Anarchists and the Haymarket Affair"

- Jill Lepore, "The Terror Last Time," New Yorker