The Homestead Strike: 1892

September 11

It’s September 11, but here on Riot-a-Day, this post isn’t about planes or towers. You can read all about that elsewhere. Today’s entry is about Homestead, when the terror was America’s rulers turning rifles against Americans.

A Town Under Siege

Homestead wasn’t just a steel mill. It was a company fortress where Carnegie Steel squeezed every ounce of sweat it could from its workers. Through the 1880s, wages were slashed while profits soared. Across the country labor was being broken town by town, but the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers still stood. They were one of the last strong unions in heavy industry, and that alone made them a target. The broader labor movement didn’t come rushing to their aid. The AFL, still new under Samuel Gompers, kept its distance. Homestead would fight alone.

Andrew Carnegie, America’s richest steel lord, knew what was coming and got the hell out of Dodge. He slinked off to Scotland like a coward, dodging the fight and leaving others to do his dirty work. He handed the job to his hatchet man, Henry Clay Frick. Frick already had a reputation as a union-buster who didn’t care how many bodies it took. He built a three-mile wall around the mill, strung it with barbed wire, mounted searchlights like it was a prison camp, and hired 300 Pinkertons (those bastards again) to crush his own employees. This wasn’t about keeping order. It was about making sure working people knew who was boss.

The Battle on the River

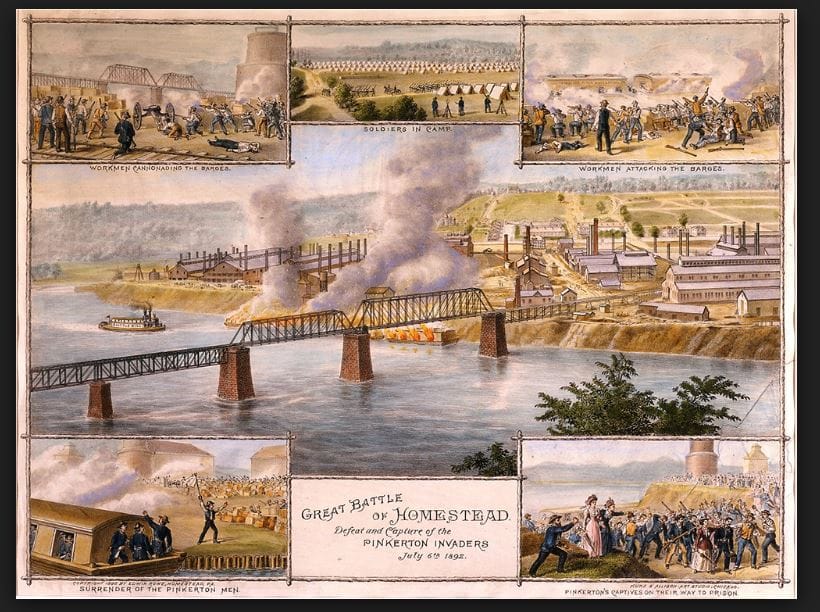

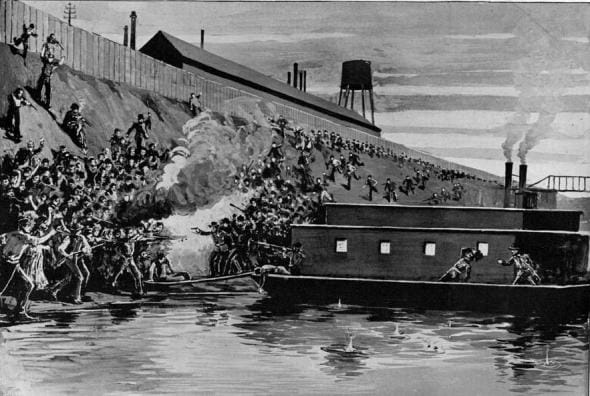

Before dawn on July 6, two barges stuffed with armed Pinkertons crept up the Monongahela River, hoping to slip in and seize the mill before anyone noticed. But Homestead was ready. Thousands of locked-out workers and their families lined the banks. Out front was Hugh O’Donnell, a young union man trying to hold the line, and John McLuckie, the town’s mayor, declaring Homestead under siege. Among them stood William Foy, a mill hand who had sweated years in the furnaces and refused to back down. A shot cracked and all hell broke loose.

For fourteen hours Homestead was a battlefield. Gunfire tore across the river. Workers rolled a flaming railcar down the tracks toward the barges. Women hurled rocks, bottles, whatever they had, and jabbed Pinkertons with hatpins when they tried to scramble ashore. Think about that: steel barons brought in a private army with rifles, and women on the riverbank fought them off with hatpins. Contemporary papers were scandalized: the New York Times reported women "attacked with clubs, stones, and hatpins," while Pittsburgh papers described wives and daughters jabbing Pinkertons as they tried to land. That’s how deep the rage ran. The hired guns found out fast that this town wouldn’t scare easy. By nightfall, the Pinkertons surrendered - their union-smashing asses well and truly kicked - bloodied, beaten, and marched through jeering crowds. Seven steelworkers and three Pinkertons were dead.

Many of those workers were Slovaks, Hungarians, and other recent immigrants. The press leaned on xenophobia, portraying them as dangerous “foreigners” rather than men and women defending their homes. The story of Homestead was spun as an immigrant riot, not an American community under siege.

The State Strikes Back

And then the cavalry showed up - not for the people, but for the bosses. Governor Robert Pattison ordered 8,000 Pennsylvania National Guard troops to occupy Homestead, marching in with artillery and Gatling guns. They didn’t come to keep the peace; they came to hand the mill right back to Frick. Scabs marched in under guard. Union leaders like Hugh O’Donnell were slapped with charges of murder and treason. None of it stuck, but it drained the fight.

And then came Alexander Berkman. Berkman was a Russian-born anarchist and close comrade/lover of Emma Goldman, both of them convinced that direct action could ignite revolution. They were wrong. On July 23 he forced his way into Frick’s office, fired two bullets into him, and drove a knife into his neck. Frick, the stubborn bastard, bleeding out, not only survived but dragged himself back to work within days, milking the moment to look like a martyr. The Homestead strikers had nothing to do with Berkman’s plot, but that didn’t matter. The national press blurred the line between anarchists and union men, smearing them all as violent radicals. Sympathy for the workers evaporated overnight.

Berkman didn’t escape. He was beaten bloody on the spot, arrested, and sentenced to 22 years in prison. He served 14 before release, later publishing Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist. He rejoined Emma Goldman, was deported to Soviet Russia in 1919, and left disillusioned when the Bolsheviks crushed dissent. He spent his last years sick and broke in Europe, and in 1936 took his own life in France. His bullet didn’t spark a revolution - it only handed Frick a propaganda victory and left Berkman ruined.

Rewriting the Story

The battle on the Monongahela had already shocked the country - Pinkertons surrendering to mill hands made front pages from New York to Chicago. But Berkman’s failed assassination attempt handed Carnegie and Frick the story they needed. The strike was rewritten as a tale of foreign anarchists and lawless mobs, not working families fighting for their lives. Within months the Amalgamated was smashed. Steel stayed non-union for fifty years. That was the point: to make an example.

History books often reduce this to a “labor dispute.” That’s bullshit. It was a war, plain and simple, and Homestead lost. What lingers aren’t just the casualty numbers but the details: women with hatpins and stones standing their ground; families patrolling the streets; the eerie silence after the Pinkertons gave up, broken only by the cries of the wounded. Homestead wasn’t a riot. It was a community under siege, fighting for its life.

The Names We Carry

The seven steelworkers killed were Joseph Sotak, John E. Morris, Silas Wain, Thomas Weldon, Henry Striegel, George W. Rutter, and Peter Ferris (as recorded by historian Paul Krause in The Battle for Homestead). William Foywas shot that morning and lived with the wound for years before dying in 1903. Remember their names. Too often even the history books forget they were people, with lives and names worth carrying forward.

The Story We Carry

Homestead was not a riot. It was a battle in a long-running class war that defined much of the 19th and 20th century. Carnegie paid for a private army to kill his own employees. Frick ordered it. The state backed it. The dead weren’t foreign enemies. They were Americans, murdered in defense of profit.

Carnegie faced no real consequences. He slinked back from Scotland, sold his empire to J.P. Morgan a decade later, and spent his twilight years polishing his halo with libraries and concert halls. His name still graces foundations and charities, whispered reverently on NPR and museum walls, as if bricks, and books, and grants could wash away the blood at Homestead. Frick survived Berkman’s bullets, doubled down on business, and lived rich until 1929, hated by workers to the end. The men who ordered the killings walked away famous and wealthy. The people who died are mostly forgotten.

And Homestead cast a long shadow. For decades bosses pointed to it as proof that unions could be broken, while workers remembered the cost of standing up and how alone they had been left. Steel stayed non-union until the 1930s, when a new generation finally forced their way back in.

On this September 11, remember Homestead. Remember that the greatest terror against Americans has so often come not from abroad, but from the men in the boardrooms who already owned too damn much and still wanted more.

Sources

- Paul Krause, The Battle for Homestead, 1880–1892 (University of Pittsburgh Press, 1992)

- David Montgomery, The Fall of the House of Labor: The Workplace, the State, and American Labor Activism, 1865–1925 (Cambridge University Press, 1987)

- AFL-CIO: "Homestead Strike" historical summary (notes 7 workers and 3 Pinkertons killed; 8,500 National Guard deployed)

- PBS American Experience: "The Homestead Strike" resources

- New York Times, July 7, 1892 (reporting women attacking Pinkertons with clubs, stones, and hatpins)

- Pittsburgh newspaper archives (Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh Post)

- Wikipedia, "Homestead Strike" (overview, militia numbers, casualties, ethnic composition)

- Governor Robert Pattison’s deployment orders for the Pennsylvania National Guard (contemporary accounts)

- Accounts of immigrant workers (Slovak, Hungarian, and others) in Krause, The Battle for Homestead