The Lattimer Massacre: 1897

The Bigger Picture

The massacre at Lattimer was not just about coal. It was about immigration, power, and who counted as American. In the 1890s, a global depression drove millions out of Eastern and Southern Europe. Farmers in Poland and Slovakia faced poverty and conscription. Italians and Lithuanians fled hunger and repression. Letters home promised steady work in America, even if it meant the mines.

Mine owners wanted these immigrants as cheap labor. They used them to break strikes, undercut older Irish and Welsh miners, and keep wages low. Newspapers and politicians painted them as dangerous outsiders, “un-American” and disposable. The mix of economic collapse and xenophobia fueled violence then as it does today. Lattimer shows how deadly that combination can be.

A Company Town That Owned Everything

Anthracite was no ordinary coal. It was the hard, clean-burning fuel that kept Gilded Age mansions warm and drove the furnaces of American industry. The rich shoveled it into parlor stoves in Philadelphia and New York while the poor tore it out of the ground just over a hundred miles away in Hazleton’s coal patches. In Pennsylvania’s anthracite region, the company owned the houses, the stores, even the water. Miners spent twelve hours in seams so narrow they crawled on hands and knees, their lamps burning low as dust filled their lungs. Pay came in company scrip, and bread or soap at the company store cost twice the market price. Families lived on the edge, with children coughing through the night while fathers trudged back to the pits at dawn.

Most of these miners were immigrants - Poles, Slovaks, Lithuanians - who had crossed an ocean only to be treated as expendable. In September 1897, after yet another round of wage cuts, they drew a line.

The March from Harwood

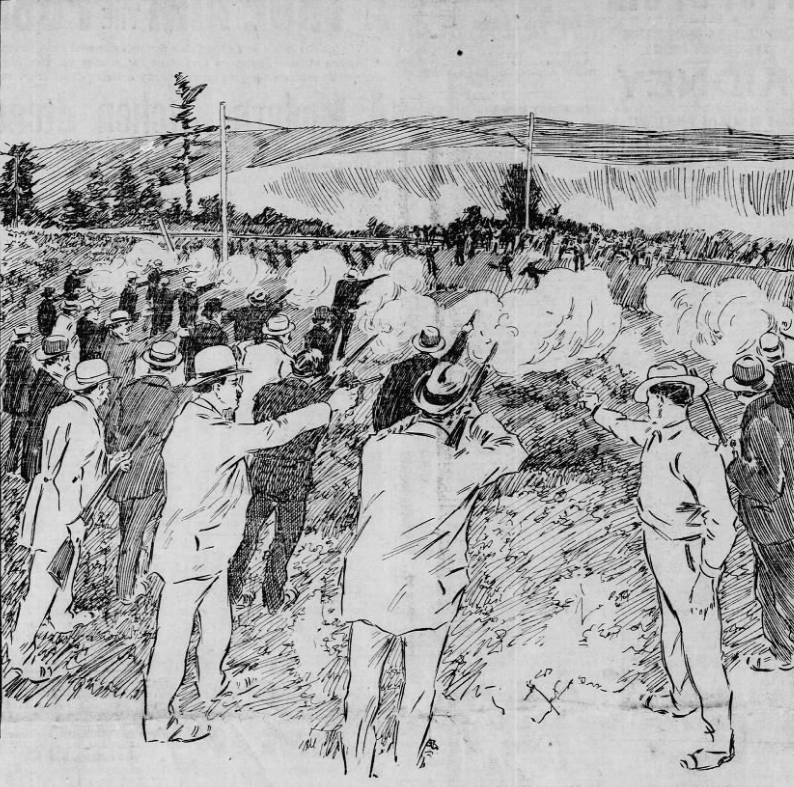

On September 10, about 400 strikers set out from Harwood to march to Lattimer and support a walkout there. They carried no weapons, only banners and their voices. Among them were men like John Pustay and Andrew Kollick, Slovak miners who had crossed the Atlantic for steady work. They marched side by side with neighbors and brothers, demanding a wage they could live on and an end to abuse.

Blood on the Road

Waiting outside Lattimer was Sheriff James Martin of Luzerne County. Martin and his posse of roughly 80 armed deputies claimed they were there to keep order. What they did instead was murder. When the marchers refused to turn back, the deputies opened fire on an unarmed crowd. Nineteen miners were killed and nearly 50 wounded. Most were Polish and Slovak. Court testimony later confirmed that many had been shot in the back while fleeing. A peaceful march ended in slaughter.

Aftermath

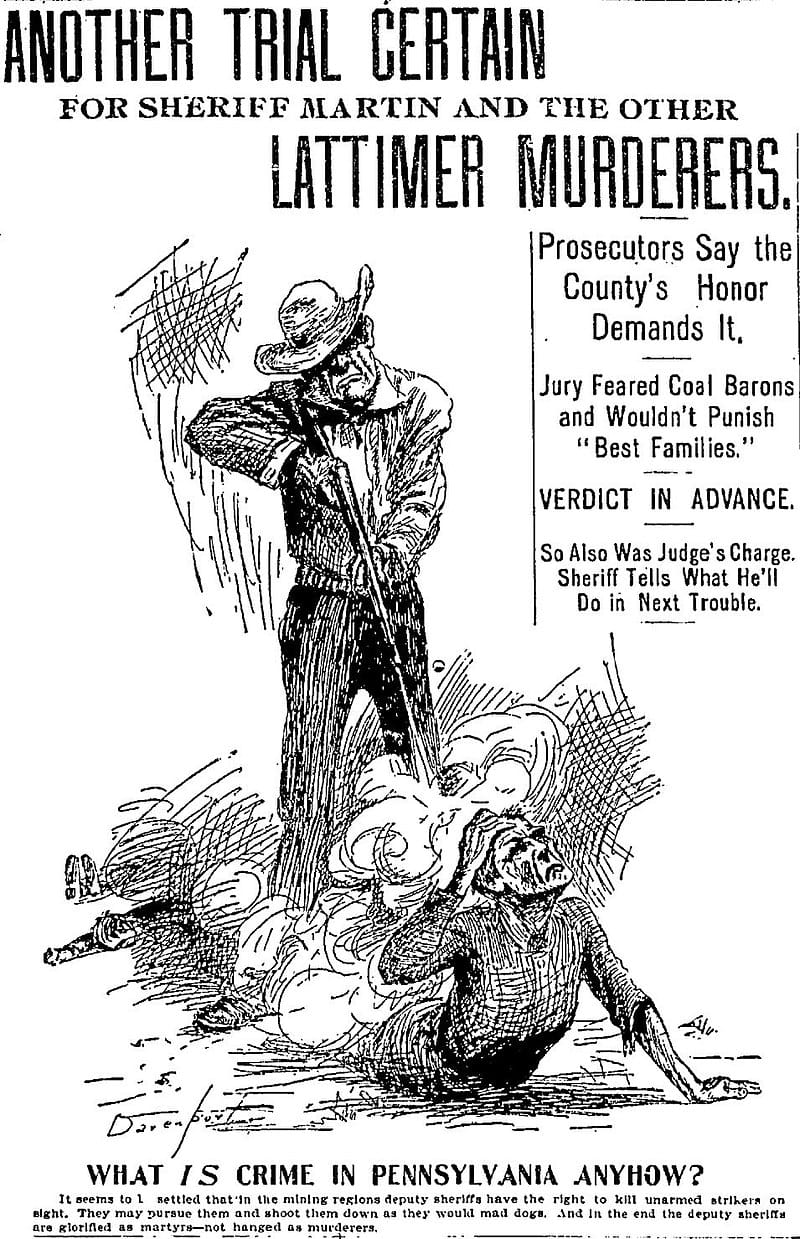

The miners’ families buried their dead, but the courts buried justice. Sheriff James Martin was indicted for the killing of miner Michael Cheslock and tried first. He walked free. Then 73 of his deputies were put on trial for the other deaths. Witnesses swore that men had been shot in the back while fleeing, but the jury still acquitted every last one of them. Two trials, two whitewashes, and the message was clear: immigrant lives meant nothing in the eyes of the law. Widows and children filled the streets in mourning, fueling anger and sympathy across the coalfields.

Why It Matters

Lattimer should have broken the miners. Instead, it hardened them. Membership in the United Mine Workers tripled as immigrant miners and their families swore never again to walk unorganized. For the first time, Poles, Slovaks, and Lithuanians joined in large numbers, turning the union into a truly multi-ethnic movement.

The villains - Sheriff Martin and his deputies - retired in comfort. The heroes - men like John Pustay and Andrew Kollick - died on a dirt road for daring to demand dignity. The names of the murdered are carved in stone at a memorial today, though in 1897 the press mostly called them “foreign agitators.”

This was not a riot. It was a massacre. Deputies gunned down immigrant miners, many shot in the back as they ran. The deadliest enemy of working people in this country has always been the bosses and their hired guns, not some foreign foe.

Sources

- Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Vol. 2 (1955)

- Paul Krause, The Battle for Homestead (for comparison to other strikes)

- Robert Asher and Ronald Edsforth, The Rise of the Working-Class Shareholder (context on anthracite labor)

- Harold Aurand, Coalcracker Culture: Work and Values in Pennsylvania Anthracite, 1835-1935 (2003)

- Anthony F.C. Wallace, St. Clair: A Nineteenth-Century Coal Town's Experience with a Disaster-Prone Industry(1987)

- Wikipedia, "Lattimer massacre" (overview of dates, numbers, deputies, trials)

- Contemporary press reports in the New York Times and Philadelphia Inquirer (1897 coverage)

- United Mine Workers of America historical materials (membership growth after Lattimer)