The Ludlow Massacre: 1914

Not a Clash, a Massacre

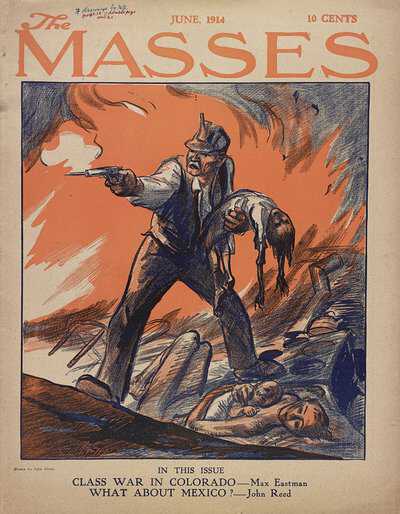

On April 20, 1914, in the coal fields of southern Colorado, the Colorado National Guard and company thugs opened fire on a tent colony of striking miners and their families. Let’s be clear: this wasn’t a “clash” or a “disturbance.” It was the state and the bosses teaming up to murder working people in broad daylight. The governor called it law and order. The Rockefellers called it business. The families who crawled out of the ashes called it what it was: massacre.

The Bigger Picture

Ludlow wasn’t some isolated tragedy. The whole country was on edge. Just two years earlier, women and children had marched in Lawrence, demanding Bread and Roses. In 1913, copper miners and their families in Calumet died when company goons turned a Christmas party into carnage. Across Europe, workers were striking, socialists were rising, and the ruling class was terrified. Months after Ludlow, World War I would swallow the globe. Coal was the fuel that made all of it run, and the miners in Colorado were treated like expendable parts in the machine.

The Strike

In September 1913, the United Mine Workers called a strike against John D. Rockefeller’s Colorado Fuel & Iron Company. What the miners wanted was hardly radical: a union, laws already on the books enforced, wages they could live on, and homes fit for human beings. For asking for basic rights that should have already been theirs, they were thrown out of company houses. Families set up tent colonies in the dust. Ludlow was the biggest, a rough canvas city of nearly 1,200 people.

The People

Louis Tikas, a Greek immigrant and organizer, was the heart of the camp. He tried to keep the peace, even with the soldiers staring down his people with rifles. Mary Thomas and her children huddled in a pit under their tent when the bullets started flying. Felipe Neri, a Mexican American miner, took up arms at the edge of camp to defend women and kids. These weren’t nameless “agitators.” They were families - Greek, Italian, Slavic, Mexican, Black - holding together against the bosses. Tikas would be captured and executed that day. Mary Thomas and her children suffocated in the death pit. Neri fell in the fight. Their names deserve to be remembered.

The Massacre

At dawn on April 20, the Guard and mine guards rolled out machine guns. Bullets ripped through canvas. Families clawed for cover in dugout cellars. By nightfall, the camp was on fire. When it was over, the “death pit” held two women and eleven children, burned and suffocated. Louis Tikas lay shot in the back. Around 25 people died - eleven children, two women, and more than a dozen miners. As one paper admitted, it was one of the most violent moments in American labor history. And it was carried out by men in uniform, sworn to protect the public.

Aftermath

Mother Jones, already branded by a federal prosecutor as “the most dangerous woman in America” back in 1902, rushed to Colorado in the wake of the massacre. She was, as always, a complete badass. She rallied survivors, spoke at funerals, and demanded justice in the press. She rallied survivors, spoke at funerals, and demanded justice in the press. Her presence made sure Ludlow couldn’t be brushed aside as just another strike gone bad.

The killings lit a fuse. For ten days, miners across southern Colorado fought back with rifles and dynamite in what became the Ten Days War - the largest armed uprising since the Civil War. They seized mines and held their ground until the U.S. Army marched in. Not to punish the killers, but to protect Rockefeller’s property. When he finally faced Congress, Rockefeller admitted his company had armed the very troops who murdered women and kids at Ludlow. Then he hired a slick PR man named Ivy Lee to polish his image - one of the first big corporate PR campaigns in American history.

The Legacy

The massacre shocked the nation. Mother Jones called it “the worst massacre of women and children in America.” Writers and musicians turned it into legend - Woody Guthrie sang it, union halls taught it, families never forgot it. For the miners, it was proof written in blood: the state and the bosses would kill to keep coal cheap and unions weak. For Rockefeller, it was a PR headache that money and charity could eventually bury.

Ludlow was not an accident. Families were murdered so coal trains could keep running and profits could keep flowing. A century later, the names of the dead are read aloud at the Ludlow memorial, now a U.S. National Historic Landmark. The Rockefellers may have thought they erased them. They didn’t. The memory still burns.

Sources

- Thomas G. Andrews, Killing for Coal: America’s Deadliest Labor War. Harvard University Press, 2008.

- “War in the Coalfields: The Ludlow Massacre and Its Impact on the Eight-Hour Workday,” National Park Service.

- Congressional testimony of John D. Rockefeller Jr. on the Colorado coal strike, 1915 (New York Times and History Matters archive).

- Zeese Papanikolas, Buried Unsung: Louis Tikas and the Ludlow Massacre. University of Utah Press, 1982.

- Elliott J. Gorn, Mother Jones: The Most Dangerous Woman in America. Hill and Wang, 2001.

- “The Ludlow Massacre,” New York Times, April 1914 (contemporary press account).

- ResearchGate, “Shocking Atrocities in Colorado: Newspapers’ Responses to the Ludlow Massacre.”