The New Orleans Massacre, 1866

The Civil War ended in 1865. The killing didn't.

Barely a year after Appomattox, the same bastards who'd fought for slavery were back in power. In Memphis that May, white mobs murdered 46 Black residents. Two months later in New Orleans, the city's own police force did the slaughtering.

General Philip Sheridan had seen Fort Pillow, where Confederates murdered surrendering Black soldiers. He knew a massacre when he saw one.

The Creole Radicals

New Orleans had something the rest of the South didn't - a sophisticated Afro-Creole community of free people of color who'd owned property, run businesses, and organized politically for decades. They published the New Orleans Tribune, the country's first Black-run daily newspaper, in French and English. These weren't people asking politely. They were demanding what was theirs.

Louisiana's 1864 constitution abolished slavery but stopped short of Black male suffrage. By 1866, former Confederates controlled the legislature and passed Black Codes designed to recreate slavery by another name. The Creole Radicals decided to reconvene the constitutional convention to finish the job - extend voting rights, eliminate the Black Codes, bar ex-Confederates from voting.

Was it legally questionable? Yeah. Did that justify murder? Hell no.

Confederates in Uniform

In May 1866, Confederate sympathizer John T. Monroe returned as mayor. Former Confederate general Harry T. Hays became sheriff and recruited an all-white police force of ex-Confederate soldiers. The Democratic press stoked white rage. On July 27, hundreds of Black supporters rallied. The stage was set.

July 30, 1866

Only 25 delegates showed up that morning at the Mechanics Institute - not enough for a quorum. While they waited, about 200 Black men, mostly unarmed Union veterans, marched toward the building with a band and flags.

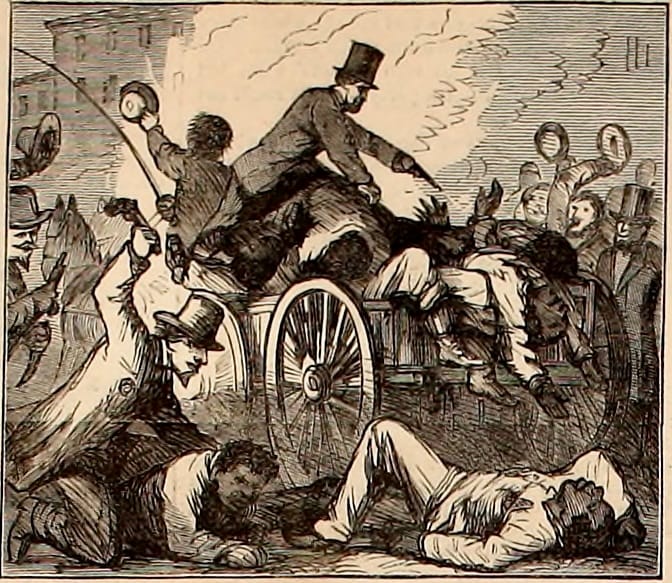

Across from the Institute, hundreds of white men waited. Ex-Confederates, police, firemen, armed with guns, clubs, knives. When the marchers arrived, the mob attacked. The marchers fled into the Institute. The police joined the slaughter.

Fire sirens rang out - the signal. Police surrounded the building and opened fire. Inside, delegates broke up chairs to fight back. Those who tried to surrender were beaten or shot.

Anthony Paul Dostie, a white dentist and fierce abolitionist, waved an American flag from the podium. A bullet tore through his arm. Police dragged him outside to the mob. They clubbed, stabbed, and shot him. He died six days later.

The killing spread. Black men were hunted through streets, pulled off streetcars, murdered in doorways. Federal troops were stationed in the city. They arrived after it was over.

Official count: 38 dead (34 Black, 3 white Republicans, 1 white attacker), 146 wounded. Most historians estimate 40-50 dead. Among them: Victor Lacroix, John Henderson Jr., Reverend Jotham Horton, and dozens whose names survived only in church ledgers.

Fighting for the Story

Four days later, the New Orleans Tribune published "Notes to Serve in the History of the New Orleans Massacre." They knew the white press would call it a riot. While white newspapers blamed "radical agitators," the Tribune documented the truth: defenseless people murdered in cold blood, children pulled from streetcars and killed on Canal Street.

Sheridan telegraphed Grant: "It was no riot. It was an absolute massacre by the police, which was not excelled in murderous cruelty by that of Fort Pillow. It was a murder which the Mayor and police perpetrated without the shadow of a necessity."

President Andrew Johnson could have sent federal troops. Instead, he telegraphed the Louisiana Attorney General, siding with the state. His silence was permission.

The Backlash

News swept the North. Cartoonist Thomas Nast drew Johnson as a Roman emperor watching Black citizens massacred. In the 1866 midterms, Radical Republicans won 77% of Congress - enough to override any Johnson veto.

They passed the First Reconstruction Act, imposing military rule on the South. They ratified the 14th Amendment (citizenship) and 15th (voting rights). Sheridan removed Monroe and the officials who'd enabled the massacre.

In November 1867, under military protection, survivors helped write a new Louisiana constitution - integrated schools, integrated transportation, equal justice. It lasted about a decade.

What They Got Away With

Monroe was removed from office. No charges. Hays was never prosecuted. The police who murdered unarmed men - not one saw a courtroom. No one was held accountable.

On the one-year anniversary, a poet using the pseudonym Camille Naudin published "Ode to the Martyrs," noting what everyone already knew: not a single perpetrator had been convicted.

The massacre taught the South you can murder your way back to power. Within a decade, Reconstruction collapsed. The men who spilled blood walked free.

For over a century, it was erased or sanitized into a "riot." The Roosevelt Hotel stands where the Mechanics Institute once did. When workers demolished the old building in 1905, they found a skeleton in the attic clutching a gun.

In 2024 - 158 years later - the city finally placed a marker and issued an apology.

Sources

- James G. Hollandsworth Jr., An Absolute Massacre: The New Orleans Race Riot of July 30, 1866 (Louisiana State University Press, 2001)

- Gilles Vandal, The New Orleans Riot of 1866: Anatomy of a Tragedy (Center for Louisiana Studies, 1984)

- Fatima Shaik, Economy Hall: The Hidden History of a Free Black Brotherhood (Historic New Orleans Collection, 2021)

- Clint Bruce, "Notes to Serve in the History of the New Orleans Massacre: The Stance of the New Orleans Tribune," 64 Parishes (2019)

- Philip H. Sheridan telegram to Ulysses S. Grant, August 2, 1866

- New Orleans Tribune, August 3, 1866

- U.S. National Park Service, "An Absolute Massacre - The New Orleans Slaughter of July 30, 1866"

- Harper's Weekly, September 8, 1866