The Pana Massacre: 1899

April 10, 1899. Pana, Illinois. Another coal town turned killing ground, but this one was different. Less than a year after Virden, the bosses had learned a lesson: if solidarity could beat them, they would smash solidarity with race. What followed wasn’t remembered as a strike or even a massacre. The headlines called it a “race war.” That was the point. The company wanted the public to see workers murdering each other while the real villains stayed clean behind their stockade walls.

The Setup

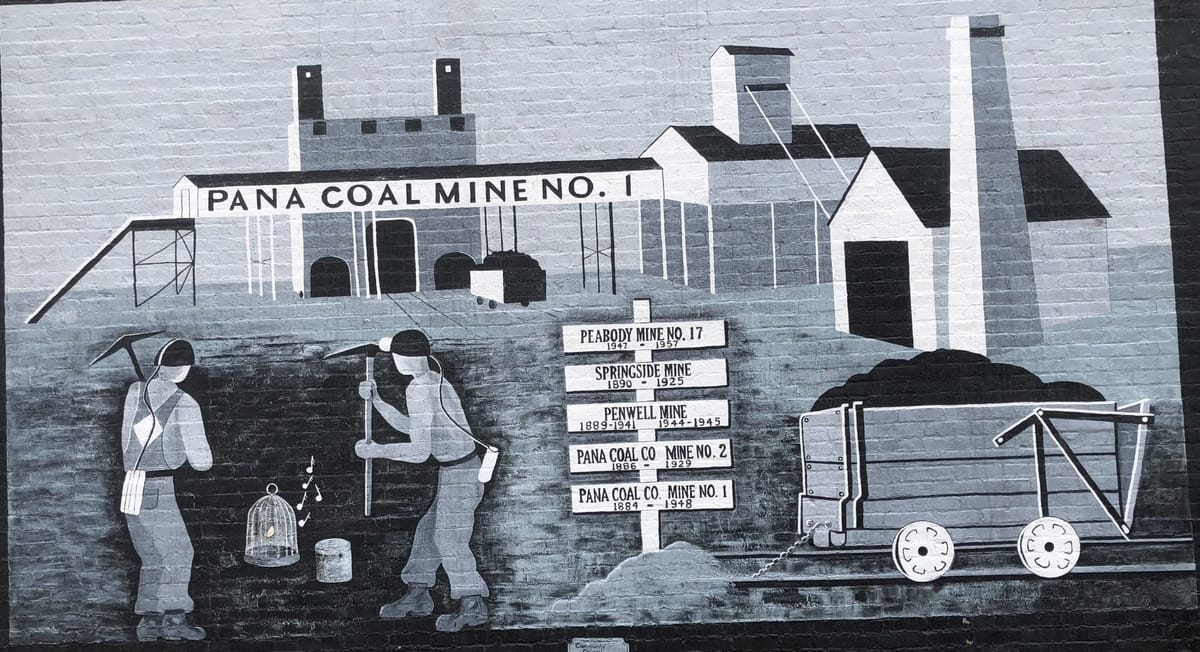

The Panic of 1893 had gutted the coalfields, and miners fought for scraps. After the Virden Massacre, the United Mine Workers tried to keep Illinois united under a fair wage scale. The Pana Coal Company had no intention of playing ball. They slashed pay, rejected union terms, and recruited Black miners out of Alabama to break the strike. Recruiters promised steady jobs, fair pay, and safe ground. They did not say a word about the strike. Many of the men only discovered the truth when they stepped off the train in Illinois and saw armed guards at the gates.

By 1899, they knew exactly what was happening. They had lived for months under guard, penned in near the mine, their families threatened. Some were even deputized by the company, shoved into a fight they hadn’t asked for. They weren’t villains. They were desperate men conned into being pawns, and then forced to carry rifles to defend the company’s stockade. One affidavit from two of the Alabama miners, Benjamin Lynch and Jack Anderson, swore that recruiters told them there was “no trouble here” and that the mine was “newly opened.” They realized too late they had been lured into a strike zone under false pretenses.

April 10, 1899

It came to a head that spring morning. Shots erupted between union miners, company deputies, and Black strikebreakers. When it ended, seven people lay dead. Five were Black miners: Henry Johnson, Louis Hooks, James L. James, Charles Watkins, and Julia Dash — a miner’s wife caught in the crossfire. Two whites died, including Deputy Sheriff Frank Hayes. Dozens more were wounded. Families huddled in boardinghouses and shacks as bullets tore through Pana. The bosses had turned a wage fight into slaughter.

Aftermath

The newspapers wasted no time. They called it a “race war,” as if that explained everything. That branding stuck, and it poisoned labor relations for years. But the truth was simpler and uglier. The company created the conditions, imported men and families under false pretenses, armed the deputies, and let the shooting start. The dead were buried, widows wept, and the union staggered. The Pana Coal Company’s plan had worked: solidarity was broken, and the narrative had been flipped from class war to race riot.

Why It Matters

Pana wasn’t just another coalfield clash. It was extraordinary because the company’s strategy worked. Virden had shown that solidarity across lines could win. Pana showed how fragile that solidarity was when race was weaponized. The cost was seven lives, including a woman who had no weapon in her hand. The headlines buried the story of deception and corporate power, and America remembered Pana as a race riot instead of what it really was: a massacre engineered from above.

That’s the lesson that still echoes. Divide workers by race, nationality, gender, or anything else, and the bosses keep winning. The graves in Pana aren’t just history. They are a warning of what happens when solidarity breaks and the real enemy goes free.

Sources

- The Indianapolis Journal, April 11, 1899: “Shot to Death: Seven People Killed in a Miners Riot at Pana, Ill.”

- Affidavit of Benjamin Lynch and Jack Anderson, Alabama miners recruited to Pana, quoted in: "Virden and Pana Mine Wars, 1898-1899." Macoupin County Mining History Project.

- N. Lenstra, “The African-American Mining Experience in Illinois, 1800-1920.” Western Illinois Historical Review (2012).

- “Pana riot,” Wikipedia, citing Illinois State Journal reports, April 1899.

- Melvyn Dubofsky & Warren Van Tine, John L. Lewis: A Biography. University of Illinois Press, 1977. (Context on UMWA and coalfield struggles).