The Peekskill Riot

Paul Robeson was scheduled to perform in Peekskill, New York, in September 1949. Not just Paul, Pete Seeger and other progressive artists were also slated to take the stage. It should have been a celebration of music and solidarity. Instead, it became a window into how fear and hate get whipped up, and how quickly neighbors can be turned into attackers.

The Panic

This was not spontaneous violence. It was stoked. Local newspapers ran inflammatory headlines, calling Robeson a communist traitor and smearing anyone who came to hear him as un-American agitators. The local American Legion took the lead, declaring themselves defenders of patriotism and calling on people to oppose Robeson’s concert. Politicians climbed aboard the Red Scare bandwagon, eager to prove their loyalty by painting civil rights and labor movements as fronts for Moscow. Fear of communism became a weapon against Black activism, union solidarity, and anyone who dared to step outside the line.

It was a moral panic in the classic sense: a vulnerable group demonized, fear amplified, and violence justified in the name of protecting “our way of life.”

The First Night

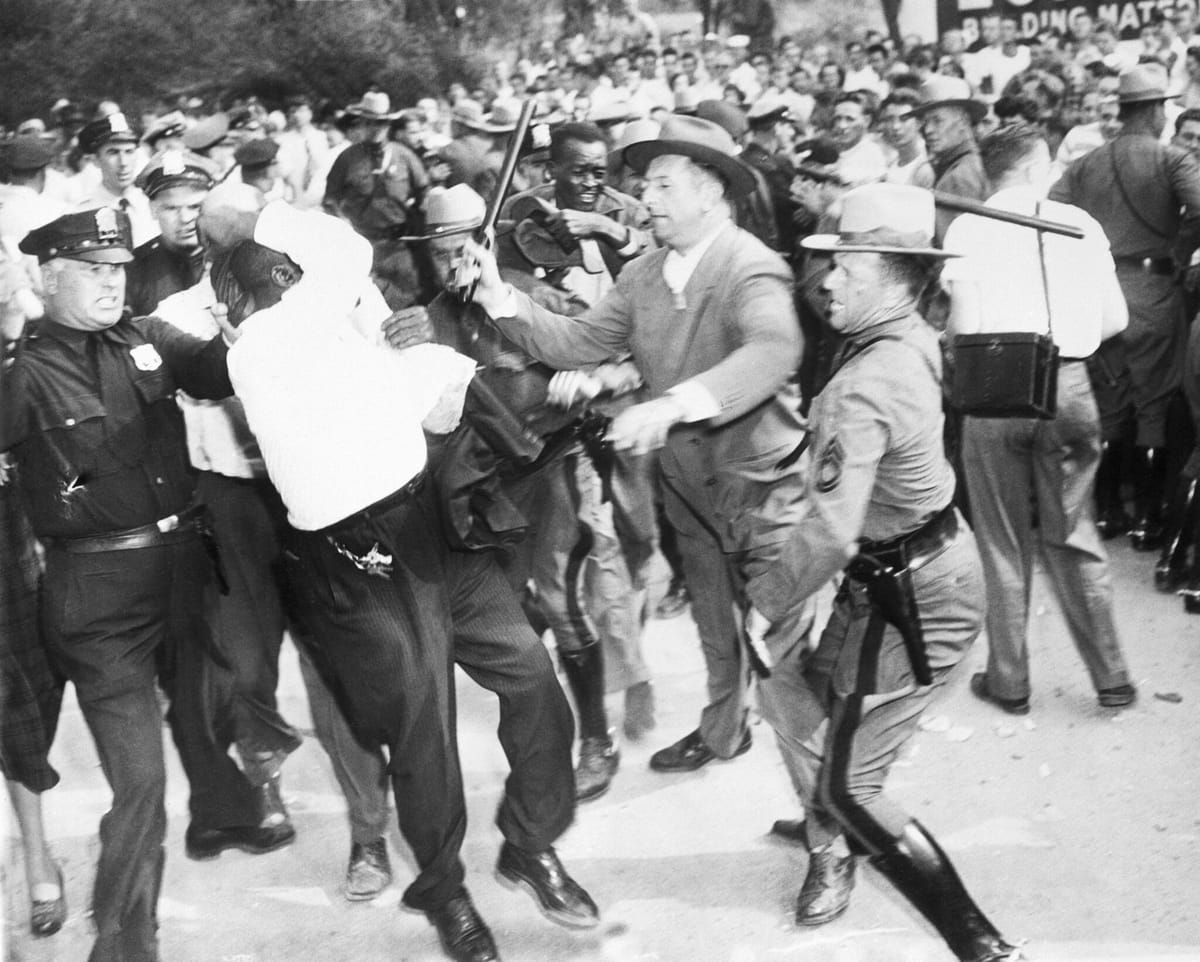

The Civil Rights Congress and local union allies organized the concert on August 27. But it never happened. Roughly 2,500 white locals, many stirred up by the American Legion and inflammatory headlines, descended on the venue. They attacked the roughly 15,000 people who had gathered to hear Robeson and the other artists, pelting them with rocks and swinging clubs and fists. People who came for music left bloodied. Cars were overturned and windows smashed. Dozens were injured, and Robeson never even made it to the stage. The attackers called it patriotism. The police called it a “disturbance.” In truth, it was a riot, one encouraged by those in power. Police were present, but not to protect the concertgoers. They stood by, and in some cases joined in, while the mob unleashed violence.

The Second Attempt

A week later, on September 4, organizers tried again. This time, thousands came, determined not to be silenced. Union members, veterans, and ordinary working families showed up to support Robeson. They set up security lines, linked arms, and sang. Inside, the concert went forward, Robeson sang defiantly, his voice carrying over the hostility waiting beyond the gates.

When the show ended, the violence began. As the crowd drove home, mobs lay in wait along the roads. They hurled rocks through windshields, dragged people from cars, and beat them in the streets. Pete Seeger’s family car was smashed, his young son nearly hit by flying glass. Concertgoers described it as an ambush. Once again, the police were there, but not to stop the attacks, they watched, and in some cases participated.

The People

The crowd that came to hear Robeson wasn’t a cabal of radicals. They were teachers, veterans, union members, churchgoers, and families with kids. They came because they believed music could be a form of resistance, because they wanted to stand with a Black artist who had the courage to speak truth to power. They paid for it in broken bones and shattered glass, demonized by neighbors and abandoned by officials who should have defended them.

The Aftermath

The violence made national headlines. Civil rights leaders, unions, and progressives denounced the attacks, but local authorities doubled down, blaming Robeson and his supporters instead of the mob. There were no serious prosecutions. Robeson’s reputation took another hit in the press, and the government went further: in 1950 the State Department revoked the passport of an American citizen. His only crime was refusing to parrot their line and daring to criticize racism at home and colonialism abroad. For eight years he was trapped inside his own country, silenced on the international stage until the Supreme Court finally forced the government to back down.

In a day when the State Department once again floats the idea of pulling passports over speech it doesn’t like, this history matters. Robeson was punished not for violence, not for crime, but for words and songs that threatened the powerful. For the Left, Peekskill and its aftermath became a rallying cry, proof that the Red Scare was not just about speeches in Washington but real blood in the streets. For the Right, it was painted as a victory over “subversives.”

The Story We Carry

The Peekskill Riot wasn’t about music. It was about power. About how quickly a moral panic can be weaponized, how easy it is to brand ordinary people as enemies when the press, politicians, and self-appointed patriots decide to light the fuse. Paul Robeson stood for labor, for peace, for equality. That was enough to make him a target.

The mobs who attacked him and his supporters claimed they were defending America. In reality, they were defending white supremacy and the fragile comfort of a nation unwilling to face its own fear and hate.

Sources

- Philip S. Foner, Paul Robeson Speaks (1978)

- Howard Fast, Peekskill USA (1951)

- Paul Robeson Jr., The Undiscovered Paul Robeson (2001)

- “The Peekskill Riots, 1949,” New York State Archives

- New York Times and Daily Worker coverage, August–September 1949

- Eric Foner, The Story of American Freedom (1998)

- Martin Duberman, Paul Robeson: A Biography (1988)

- Supreme Court case Kent v. Dulles (1958)