The Snow Riot

White Supremacy and Moral Panic in Washington DC.

In August 1835, Washington, D.C. exploded. Not with justice or rebellion, but with a white mob turning on free Black residents. The excuse was a man named Beverly Snow.

Beverly Snow

Beverly Snow’s story is astonishing. Born enslaved in Virginia, he won his freedom and made his way to Washington, D.C. There he became a chef and entrepreneur, opening the Epicurean Eating House. His tables served Black and white clientele, free and enslaved people alike. A rare and radical kind of space in the 1830s capital. Snow’s success made him a target long before the lies that sparked the riot.

Rumors spread that Snow had insulted white women. It was a lie, but it was enough. A cheap, lazy lie, the kind that racist society always stood ready to believe. It didn’t need to be clever. Just mention white womanhood and watch the mob load their guns. One local paper claimed he had "used very indecent and disrespectful language concerning the wives and daughters of Mechanics." Another report repeated that he had insulted the "wives of white mechanics who work at the Navy Yard." "God knows whether he said those things or not," wrote Navy Yard worker Michael Shiner in his diary, a witness to the panic and the lies. The accusation didn’t need truth to work. It only needed a mob willing to believe it.

The Mob

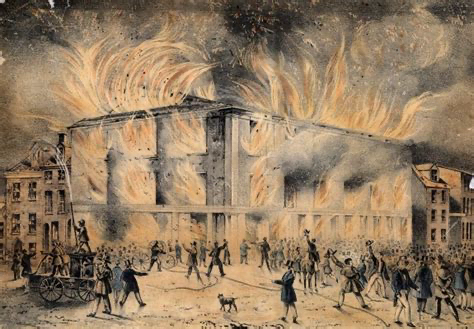

White mechanics and apprentices, angry at both their employers and the sight of free Black competition, chose an easier target than their bosses. They stormed Snow’s eating house, smashed it apart, and ran him out of town. Then they turned on schools that taught Black children, churches that served Black congregations, and the homes of Black leaders. They ransacked buildings looking for abolitionist newspapers and pamphlets, convinced that Black education and antislavery ideas were a greater threat than the bosses who exploited their labor.

The Climate

Why Snow? Because he represented possibility. He was a Black man making a life, running a business, showing dignity in a city that was supposed to deny him all of that. He became a scapegoat not just because of rumor but because of the political and economic climate. Newspapers stirred resentment toward free Black workers, painting them as unfair competitors who drove down wages. Politicians and elites found it easier to let mobs unleash their fury downward than risk that fury being directed at them. Snow’s very existence as a free and successful man became the target for white rage that might otherwise have confronted the bosses.

This was also a moral panic, one of many that run through American history. Newspapers spoke of "menacing assemblages" in the streets and amplified the lie until it felt like truth. The pattern repeats. Elites and media manufacture hysteria, label a community as dangerous, and ordinary people are pushed to attack their neighbors instead of their oppressors.

The Violence

The mob violence raged for three nights. Dozens of Black families were terrorized. Snow fled for his life. No one was punished. The National Intelligencer marveled at how far the city had fallen into panic: "We could not have believed it possible that we should live to see the Public Offices garrisoned by the clerks, with United States troops posted at their doors, and their windows barricaded, to defend them against citizens of Washington." City leaders downplayed the attacks, calling them disturbances. Disturbances. Smashed schools, dead neighbors, and troops at the doors of public offices. The message was clear: white violence was tolerated, Black success was not.

The Reckoning

The Snow Riot was not just a riot. It was an act of racial and class scapegoating. White workers had real grievances with their employers. But instead of striking at the bosses, they chose to unleash violence on their Black neighbors and on abolitionists. They were not powerless dupes. They were men who chose white supremacy over solidarity, cheered on by a press and political class eager to see their rage misdirected. Spare us the idea that they “didn’t know better.” They knew exactly what they were doing.

It happened in 1835. It happened again in the Red Summer of 1919, in Tulsa in 1921, in Rosewood in 1923. It happens whenever ruling power directs anger downward instead of upward. The mobs in 1835 were not just lashing out blindly. They were hunting abolitionist thought itself, destroying schools, churches, and presses to keep antislavery ideas from spreading. It was an attack on knowledge as much as on people.

And remember the word they used: riot. They always call it that. But what happened in Washington was not some mindless riot. It was racial terror, scapegoating, organized violence in defense of white supremacy. Again and again in American history, the word "riot" hides the truth of massacre, coup, or crackdown.

Look ahead 190 years and see a grim reflection. In August 2025, a president seized control of the capital’s police, mobilized over 2,000 National Guard troops in a majority-Black city, and imposed a federal state of emergency over crime, despite falling rates and local opposition. The codes have changed. Troops instead of mobs, permits instead of panic. But the message is the same. Muscle is the answer. Dissent is the threat. Black presence is the provocation.

The Aftermath

By the end of the Snow Riot, at least one Black Washingtonian was killed, others were wounded, and dozens of families were terrorized. A Black school was ransacked, churches and homes smashed, and Beverly Snow’s restaurant left in ruins. No one was held accountable. City leaders downplayed the terror as “disturbances.” To make matters worse, the city council responded not by protecting the victims but by passing new ordinances restricting Black-owned businesses, forcing them into special licensing hurdles that white-owned shops did not face. Violence in the street wasn’t enough. They had to make sure the law carried on the job. And the city obliged, putting official stamps and licenses on white supremacy as if it were just another civic duty. The violence wasn’t commemorated. It was buried, and then written into law.

Snow escaped to Pittsburgh and eventually Canada. There, he built a new life with his wife. His survival was incredible. But fleeing to live in peace showed how fragile Black freedom was, and still is, in America.

Sources:

District of Columbia, Emancipation Day: “The Snow Riot.”

Jefferson Morley, “The Snow Riot,” The Washington Post, February 6, 2005.

Naval History and Heritage Command, The Diary of Michael Shiner, 1831–1839.

Boundary Stones (WETA), “The Forgotten Story of Washington’s First Race Riot,” September 6, 2024.

Washington Mirror (1835), quoted in Morley, Washington Post.

National Intelligencer, quoted in Richmond Enquirer, August 18, 1835.

Kate Masur, An Example for All the Land: Emancipation and the Struggle over Equality in Washington, D.C.(University of North Carolina Press, 2010).

Constance McLaughlin Green, The Secret City: A History of Race Relations in the Nation’s Capital (Princeton University Press, 1967).

James Oliver Horton & Lois E. Horton, In Hope of Liberty: Culture, Community and Protest among Northern Free Blacks, 1700–1860 (Oxford University Press, 1997).