The Stono Rebellion, 1739

September 9, 1739. Twenty enslaved Angolans met near the Stono River, twenty miles southwest of Charleston. They broke into a store, took guns and ammunition, killed two shopkeepers, and marched south toward freedom with drums beating and flags flying. They shouted "Liberty!" as they walked, and for one bloody day, they meant it.

This was the largest slave uprising in British colonial America. It terrified white South Carolina so thoroughly that the colony spent the next century building a legal prison designed to make sure it never happened again.

The Promise Just South

South Carolina's rice economy was a death machine. Rice cultivation required massive labor forces working waist-deep in malarial swamps under a sun that killed. By 1739, enslaved people outnumbered whites two to one. The colony was a Black majority ruled by a white minority, and everyone knew it.

Spain wanted to bleed Britain's slave economy dry, so it made an offer: any enslaved person who reached Spanish Florida and converted to Catholicism would be freed. In 1738, the Spanish governor established Fort Mose near St. Augustine, the first legally sanctioned free Black settlement in what would become the United States. Over 100 formerly enslaved people lived there, many serving in the militia. It was 150 miles south of Charleston, and enslaved people in South Carolina knew about it.

That knowledge was a weapon all its own. Many enslaved people from the Kongo region were already Catholic (Kongo had been Catholic since the 1490s) and spoke Portuguese, which meant they could understand Spanish proclamations. They'd been sold into British slavery after civil wars in Kongo swept up trained soldiers and educated men. Some, like the rebellion's leader Jemmy, likely had military experience. They knew how to organize, how to fight, and they knew freedom wasn't just a dream. It was 150 miles south.

The March

The timing was deliberate. September 9, 1739, the day after the Feast of the Nativity of Mary, connected their Catholic past to their revolutionary present. It was a Sunday morning, when white planters attended church. Just weeks earlier, the colonial assembly had passed the Security Act requiring all white men to carry weapons even to church, but the law wasn't fully enforced yet. The rebels struck in that window.

Jemmy and about twenty others gathered near the Stono River, raided Hutchenson's store for weapons, and killed the two white men inside. They left the heads on the front steps. There was no going back.

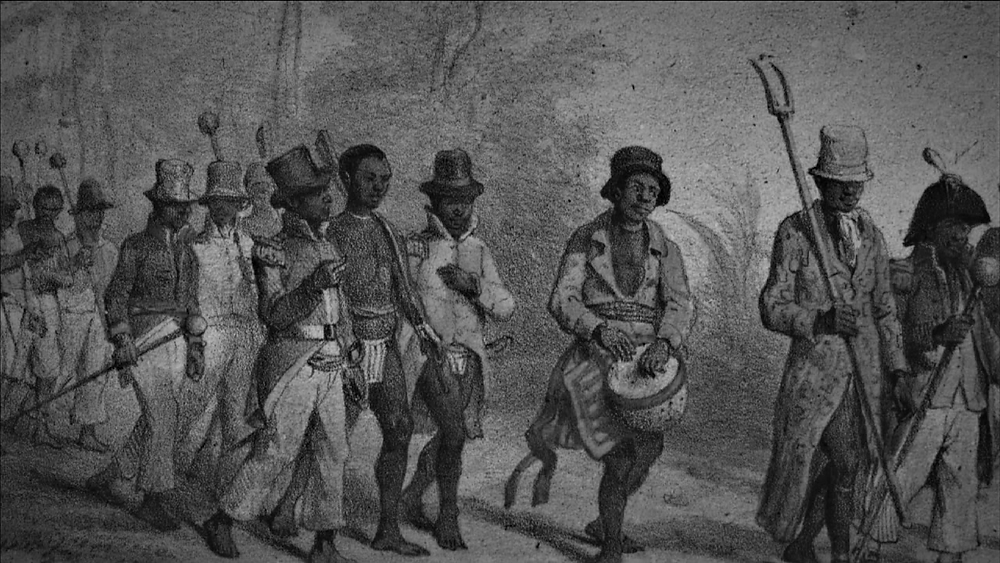

They marched south along the road toward Georgia, toward Fort Mose and Spanish Florida. Drums beating. Flags with "Liberty!" written on them. In the brutal September heat, 60, maybe 100 people moving as an army down a road through plantation country. As they moved, they burned houses (the smell of smoke and timber carried for miles), killed slaveholders, and freed or forced other enslaved people to join them. They killed about 20 whites as they went, but they also spared some. When they reached Wallace's Tavern, they didn't touch it. Wallace was known for treating his slaves decently. That detail mattered. This wasn't mindless violence. It was a calculated bid for freedom.

For about 15 miles, they marched through a landscape built on their bondage. It lasted one day.

The Killing Field

Lieutenant Governor William Bull was riding from Beaufort to Charleston that afternoon when he encountered the rebel column. He wheeled his horse around and escaped into the woods before they saw him. He spread the alarm. That accident doomed them.

By late afternoon, a mounted militia caught them in an open field near the Edisto River. White planters and officials, armed and on horseback, surrounded the rebels. The fighting was brutal and real. These weren't untrained field hands panicking under fire. Many were Kongolese soldiers who knew how to fight in formation, and they held their ground. More than 20 militiamen died before sheer numbers and firepower broke the rebel line. More than half the rebels died in that field. Some scattered into the swamps.

A week later, militiamen hunted down the survivors and killed most of them in a second engagement. The final death toll: about 20-25 white colonists and 35-50 enslaved people, though the real number is likely higher. The rebels who survived were captured and executed. Their heads were mounted on pikes along the main roads leading into Charleston, left there for weeks as a rotting warning. The message was clear: this is what happens when you reach for freedom.

Some rebels escaped the initial massacre and remained at large for months. One leader wasn't captured until 1742, three years later. But most were dead within days. Jemmy's fate is unknown. He likely died in the fighting or the executions that followed.

The Reaction

White South Carolina lost its mind. The colony imposed a 10-year moratorium on importing enslaved Africans, terrified that new arrivals (especially from the Kongo-Angola region) would bring more rebellion. When the moratorium ended, they deliberately avoided the Kongo-Angola region, seeking people they thought would be easier to break. They learned nothing except how to be more strategic in their cruelty.

In May 1740, the colonial assembly passed the Negro Act, one of the most comprehensive and brutal slave codes in colonial America. It prohibited enslaved people from growing their own food, learning to read or write, moving freely, assembling in groups, earning money, or owning drums or horns (tools that might coordinate future uprisings). It mandated a ratio of one white person for every ten enslaved people on plantations. It gave any white person the authority to arrest and punish Black people. It reduced the murder of an enslaved person by a white person to a misdemeanor, punishable by a fine.

The law codified enslaved people as legal nonentities. They couldn't testify under oath. Their lives weren't their own. Their children belonged to their masters. They couldn't defend themselves, even to save their own lives. The Negro Act remained the backbone of South Carolina's slave system until 1865, and it influenced slave codes across the South for generations.

The Men

We know Jemmy's name because he led. We know a few others through fragments in colonial records. Most remain nameless, reduced to numbers in documents written by the men who hunted them. They were Kongolese soldiers, laborers stolen from West Africa, men who'd survived the Middle Passage and years of brutal rice cultivation in Carolina's swamps. They were husbands, fathers, brothers. They chose to fight for freedom knowing they'd likely die. They lost, but they proved the lie of slavery: that human beings can be made into property, that bondage can be made natural, that resistance is futile. They proved none of it was true.

What They Built From Blood

Stono didn't end slavery. White South Carolina used it as an excuse to make slavery more brutal. The Negro Act tightened the chains for everyone who came after. The fear the rebellion sparked gave white elites justification for decades of increasingly vicious laws designed to break any hope of resistance. South Carolina's slaveholders learned that terror works if you're willing to use enough of it, and that massacres can be justified if you control the story.

But Stono also planted something else. It showed enslaved people across the colonies that organized resistance was possible, that freedom was within reach if you were willing to die for it. More uprisings followed (Gabriel's Revolt, Denmark Vesey's conspiracy, Nat Turner's Rebellion). None succeeded, but none of them had to. They kept the idea alive: that slavery was a war, not a condition. That some things are worth dying for.

The men at Stono knew Fort Mose existed. They knew freedom was real, 150 miles south. They died trying to reach it, and the colony spent a century making sure no one else would try. That's not the story of a riot. That's the story of a war that never ended.

Sources

- Peter H. Wood, Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 through the Stono Rebellion (W.W. Norton, 1974)

- Mark M. Smith, ed., Stono: Documenting and Interpreting a Southern Slave Revolt (University of South Carolina Press, 2005)

- John K. Thornton, "African Dimensions of the Stono Rebellion," American Historical Review 96 (October 1991)

- Jane Landers, Black Society in Spanish Florida (University of Illinois Press, 1999)

- Edward A. Pearson, "'A Countryside Full of Flames': A Reconsideration of the Stono Rebellion," Slavery and Abolition 17 (August 1996)

- Library of Congress, "Today in History - September 9"

- South Carolina Encyclopedia, "Stono Rebellion"