The Wilmington Ten (1971)

They didn't riot. They asked to be treated like human beings. For that, ten people - nine Black teenagers and young men, one white woman - were framed, convicted on perjured testimony, and sentenced to 282 years in prison for crimes the state knew they didn't commit.

This wasn't justice. It was a message: if you fight back against white supremacist violence, if you demand dignity in desegregated schools, if you organize Black students to stand up for themselves, we will destroy you. And North Carolina did exactly that, with help from federal agents who hunted Black organizers like it was their patriotic duty.

When "Integration" Meant Punishment

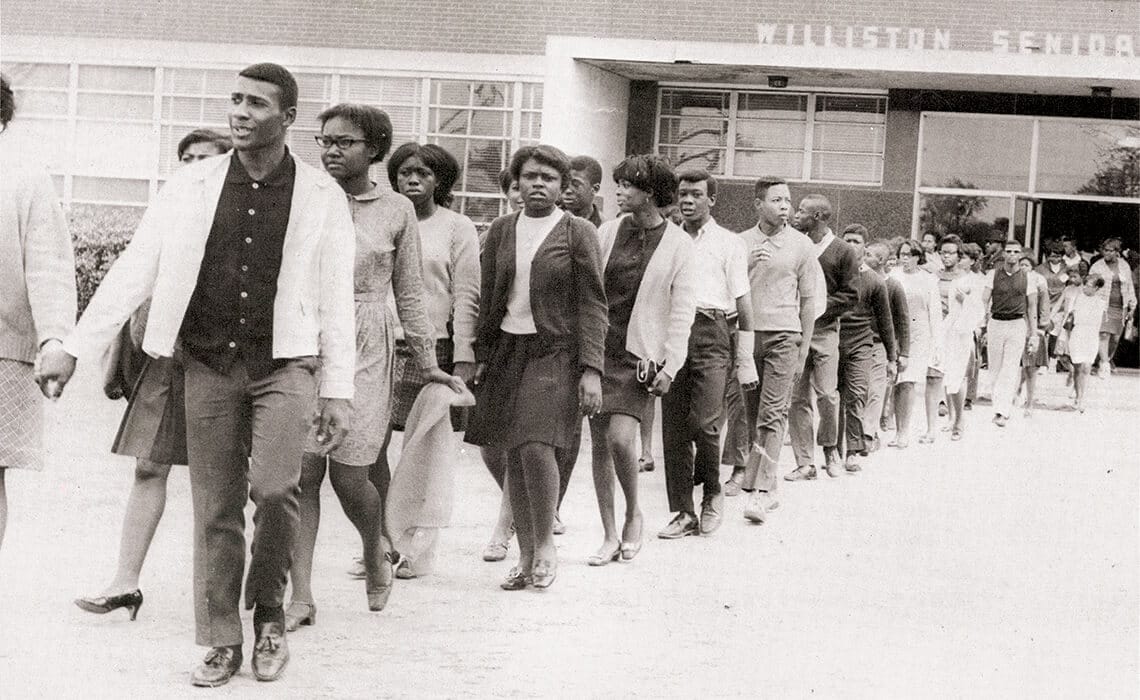

By 1971, Wilmington's schools had finally desegregated - on paper. In practice, it was a calculated humiliation. The city closed Williston High School, the Black community's pride, and fired its principals, teachers, and coaches. Black students got bused to white schools where they were sidelined, harassed, and arrested while white adults showed up on campus to taunt them. When fights broke out between white supremacists and Black students, guess who got expelled?

In January 1971, Black students had enough. They organized a boycott. When three churches and the Boys Club turned them away, student leader Connie Tindall found refuge at Gregory Congregational Church, whose white pastor Eugene Templeton opened the doors despite death threats. The United Church of Christ sent 23-year-old Rev. Benjamin Chavis, an experienced organizer from Oxford, to help structure the protest.

Chavis arrived on February 2 and immediately clarified the students' demands. The local press ran photos of him speaking to crowds with raised fists. That was all the excuse white Wilmington needed.

Armed Supremacists, Indifferent Police

Enter the Rights of White People (ROWP), a Klan-affiliated white supremacist group so extreme even the KKK didn't want them. Mostly military men from nearby bases, they held armed rallies in public parks and patrolled Black neighborhoods like an occupying force. On February 4, 1971, ROWP conducted a drive-by shooting at Gregory Congregational Church, wounding two people, including student organizer Marvin Patrick.

Police were there. They watched it happen. They did nothing. Made no arrests.

The next day, hundreds marched to City Hall demanding protection. Instead of shutting down the white vigilantes, the city sent more cops to surveil the church. Servicemen from Camp Lejeune and Fort Bragg showed up voluntarily to defend the students. The city was a powder keg, and everyone knew who lit the match - but they blamed the ones trying not to get burned.

On February 6, Mike's Grocery, a white-owned store a block from the church, was firebombed. When firefighters arrived, shots rang out. In the chaos, 17-year-old Steven Mitchell, a Black teenager, was killed by police. The next day, Harvey Cumber, a white man with a gun, crossed police lines near the church and was shot dead. The National Guard moved in on February 8, stormed the church, and found it empty.

The Frame Job

A year later - March 1972 - authorities arrested 17 people connected to the boycott. Not one member of ROWP. Not one white supremacist who fired into the church or burned businesses (at least one fire was set by a white business owner for insurance money). Just the protesters.

Ten were tried: Ben Chavis (24), Connie Tindall (21), Marvin Patrick (19), Wayne Moore (19), Reginald Epps (18), Jerry Jacobs (19), James McKoy (19), Willie Earl Vereen (18), William "Joe" Wright Jr. (19), and Ann Shepard (35), a white social worker. The trial was a farce. Assistant District Attorney Jay Stroud coached and bribed witnesses, altered statements, sought "KKK" and "Uncle Tom-type" jurors in his handwritten notes, and withheld evidence that key witness Allen Hall had a documented history of mental illness.

Hall tried to recant on the stand and had to be physically removed from the courtroom. Another witness admitted he was given a minibike for his testimony. It didn't matter. The jury, illegally stripped of most Black members, convicted all ten in October 1972. Sentences ranged from 15 years for Ann Shepard to 34 for Chavis. Combined: 282 years. For a fire where no one died.

What Happened to the Guilty

Prosecutor Jay Stroud? No consequences. Judge Robert Martin? No consequences. The federal ATF agents and FBI who tracked Chavis for years like Inspector Javert? No consequences. ROWP members who shot up a church full of teenagers? No arrests. No trials. No justice.

The Wilmington Ten became international cause célèbre. Amnesty International declared them political prisoners in 1976 - the first time they'd done so for Americans. CBS's 60 Minutes ran an exposé. James Baldwin wrote an open letter to President Jimmy Carter. When Carter lectured the Soviets about human rights, Moscow threw the Wilmington Ten back in his face.

By 1977, all three key witnesses recanted, admitting they'd been bribed or coerced into perjury. North Carolina courts didn't care. Governor Jim Hunt refused to pardon them but commuted their sentences in 1978. All ten were released by 1979. In 1980, the federal appeals court finally overturned the convictions, citing "prosecutorial misconduct." The state chose not to retry them.

They served nearly a decade for crimes they didn't commit. Four of the Ten - Jerry Jacobs, Joe Wright, Ann Shepard, and Connie Tindall - died before Governor Beverly Perdue issued posthumous pardons of innocence in 2012, forty years later. She called the convictions "tainted by naked racism." The survivors received compensation in 2013. Blood money, decades late.

The Pattern We Refuse to See

The Wilmington Ten weren't aberrations. They were part of a coordinated federal campaign to crush Black organizing in the 1970s. COINTELPRO tactics, agent provocateurs, manufactured evidence - the same tools used against the Black Panthers, used here against high school kids demanding to be treated with dignity.

This is what happens when the state decides some people aren't allowed to fight back. You can be terrorized, shot at, harassed, and expelled, but the moment you organize, the moment you defend yourselves, you become the criminals. The violence gets pinned on you. The system closes ranks. And history buries the truth for decades.

Ben Chavis went on to become a prominent civil rights leader, coining the term "environmental racism" and leading the NAACP. But he shouldn't have had to survive a frame job to do it. None of them should have spent a single day in prison. The real criminals held rallies, fired guns into churches, and walked free.

That's the legacy: white supremacist violence protected by the state, Black resistance criminalized, and justice delayed until most of the victims were already dead.

Sources

- Kenneth Robert Janken, The Wilmington Ten: Violence, Injustice, and the Rise of Black Politics in the 1970s (University of North Carolina Press, 2015)

- North Carolina Office of the Governor, "Governor Beverly Perdue Issues Pardons of Innocence to Wilmington Ten" (December 31, 2012)

- Wayne King, "The Case Against the Wilmington Ten," New York Times Magazine (December 3, 1978)

- Heather Ann Thompson, Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy (Pantheon, 2016)

- NCpedia, "Wilmington Ten" (https://www.ncpedia.org/wilmington-ten)

- Britannica, "Wilmington Ten" (https://www.britannica.com/topic/Wilmington-Ten)

- Civil Rights Division, U.S. Department of Justice, "Transcripts in the Case State of North Carolina v. Benjamin Franklin Chavis" (https://www.justice.gov/crt/)