Watts Uprising, 1965

The promise of civil rights was five days old when Watts exploded. President Johnson had just signed the Voting Rights Act. Black folks in Selma could finally vote. Meanwhile, in South Central Los Angeles, Black residents couldn't get a job, couldn't live where they wanted, and couldn't trust the cops not to beat them bloody in the street.

Nine months earlier, white Californians had voted 2-to-1 to repeal fair housing. One traffic stop lit it all on fire.

Bait and Switch

Los Angeles advertised itself as the "white spot of America" in the 1920s. Police Chief William Parker said it out loud in 1950: "Los Angeles is the white spot of the great cities of America today. It is to the advantage of the community that we keep it that way."

Between 1940 and 1965, LA's Black population exploded from 63,000 to 350,000. They came for defense jobs during World War II, recruited by companies promising good wages and decent housing. When the war ended, the plants closed. The jobs vanished. The promises evaporated. Racially restrictive housing covenants trapped Black families in neighborhoods like Watts, even after courts ruled them illegal in 1948.

Then came Proposition 14.

In November 1964, California voters repealed the Rumford Fair Housing Act by a landslide - 65% voted yes on Proposition 14. The Rumford Act had banned housing discrimination. The real estate industry spent millions telling white voters their "property rights" were under attack. Proposition 14 enshrined the right to discriminate in the state constitution. Landlords and sellers could legally refuse to rent or sell to Black families, and there was nothing anyone could do about it.

Malcolm X was assassinated three months later, in February 1965. His rhetoric about self-defense and his contempt for white liberalism resonated in Watts. Young Black men who'd heard him speak didn't buy nonviolence anymore. The Voting Rights Act passed in August. None of it mattered in Watts.

The Cage

Unemployment in Watts hit nearly 30%, double the city average. But it wasn't just joblessness - it was economic extraction. White-owned stores dominated the commercial district. They wouldn't hire Black workers. They charged higher prices than stores in white neighborhoods. They sold inferior goods. The profits left the community every night.

And then there was the LAPD.

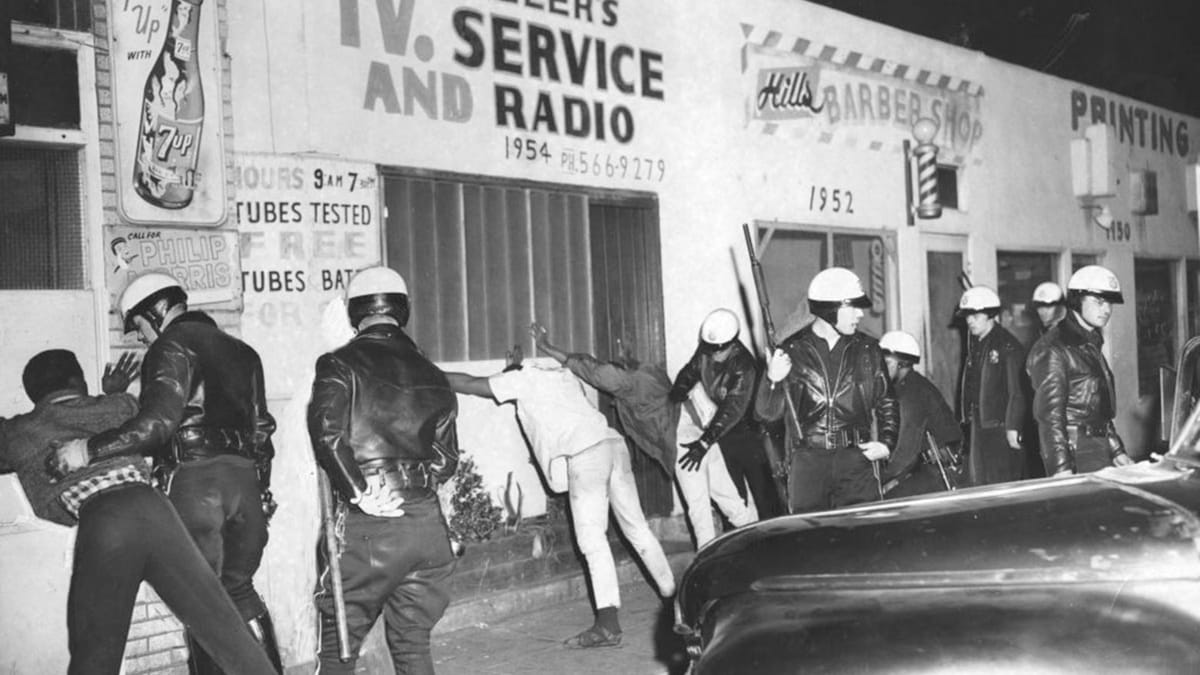

Parker ran the department like an occupying army. He recruited white cops from the South, ex-Marines who brought their racism with them. He called Black people "monkeys" and Latinos "wild tribes from Mexico." Between 1963 and 1965, LAPD killed 65 Black residents - 27 shot in the back, 25 unarmed. Civil rights leaders filed complaint after complaint - 80 in 1958 alone. The LAPD investigated itself and found almost nothing wrong. Parker blamed communists.

By August 1965, Watts wasn't a powder keg. It was a bomb.

The Frye Family

On the evening of August 11, 1965, California Highway Patrol officer Lee Minikus pulled over 21-year-old Marquette Frye near Avalon Boulevard and 116th Street, two blocks from home. Marquette had been drinking. He failed the sobriety test. His brother Ronald walked home and brought back their mother, Rena Price.

By the time Rena arrived, a crowd had gathered - 50 people, then 200, then more. Marquette had been cooperative at first, even joking with the officer. But when his mother scolded him for drunk driving, when backup arrived with shotguns, when it became clear his car would be impounded and he'd go to jail, panic set in. "Go ahead, kill me," he shouted.

Witnesses say an officer hit Marquette in the head with a baton, drawing blood. Rena jumped on an officer's back. Ronald tried to pull them apart. All three were arrested, hauled away in squad cars while the crowd threw bottles and screamed.

Rumors spread fast: a pregnant woman had been kicked, shoved, beaten by police. It didn't matter if it was true. People believed it because police violence against Black women was so common and so ignored. The crowd didn't disperse. Within an hour, Watts exploded.

Six Days in August

The uprising had a target. People didn't burn their own homes - they burned the stores that overcharged them, the shops that wouldn't hire them, the businesses owned by white people who extracted wealth and gave nothing back. A resident told KPFA radio: "I think what the people did by burning the business, I think that was good, because we don't own them, they overcharge us and everything. The best thing they did was to burn it down, completely, so the white man couldn't come back and start selling products and making money off you again."

Another voice: "The people that was looting, taking stuff home with them, they could never afford it, they would never probably have got it anyway, so this was a chance to come down to get what you want and take it home."

For six days, 30,000 people took to the streets across a 46-square-mile zone. Women protected their families, organized food and water, pulled the injured to safety. Men fought pitched battles with police. Teenagers looted grocery stores and clothing shops, taking what the system denied them. Police couldn't control it. Governor Pat Brown called in 14,000 National Guard troops. Jeeps rolled through the streets. Soldiers perched behind machine guns. Helicopters circled overhead. Watts turned into a war zone.

Parker made it worse. He called the rioters "monkeys in a zoo." He blamed the Nation of Islam without evidence, using them as scapegoats. On the final day of the uprising, as violence was subsiding, police surrounded a mosque, stormed it with guns blazing, ransacked the building next door, and set fires that destroyed the place of worship. Charges were later dropped. The Muslim community accused the LAPD of using the chaos as cover for destruction.

By August 17, it was over. At least 34 people were dead - 23 of them Black civilians, killed by police or National Guard bullets ruled "justifiable homicides." The real number was likely higher - bodies disappeared, deaths went unreported in the chaos. Over 1,000 were injured. Nearly 4,000 arrested. More than 600 buildings damaged or destroyed. Forty million dollars in property damage.

Martin Luther King arrived days later. He met residents who told him rioting was the only way to make anyone listen. One young man told him, "We won!" King responded: "How can you say you won when thirty-four Negroes are dead, your community is destroyed, and whites are using the riot as an excuse to not give you anything you asked for?" The young man's answer: "We made them pay attention to us."

What Happened Next

Governor Brown appointed the McCone Commission to investigate. Former CIA director John McCone led it. Only two of the eight members were Black. The commission released a 101-page report blaming high unemployment, bad schools, and poor housing. It made recommendations: more jobs, better education, police reform.

Almost none of it happened.

The War on Poverty money Johnson promised got swallowed by Vietnam. Police-community relations stayed toxic. Chief Parker kept his job until he died the next year. His protégé Daryl Gates took over in 1978 and made things worse, creating SWAT teams and ramping up paramilitary policing.

Marquette Frye was convicted of drunk driving, battery, and disturbing the peace. He got 90 days in jail and three years probation. Over the next decade, he was arrested 34 times. He died of pneumonia in 1986 at age 42, haunted by the uprising that started with his arrest. His mother, Rena, never recovered her impounded car - the storage fees cost more than it was worth. She died in 2013 at 97.

Officer Lee Minikus died in 2013 at 79. He never faced consequences.

What They Built

But Watts didn't just collapse. The uprising radicalized a generation. Community organizations emerged from the ashes. The Black Panther Party established a chapter in LA, monitoring police and running survival programs. Former gang members joined the movement. The Watts Writers Workshop was founded, giving voice to the neighborhood's poets and storytellers. The Mafundi Institute taught African history and culture. The Westminster Neighborhood Association organized tenant rights campaigns.

Women led much of this work. They built community centers, organized food programs, fought for better schools. They didn't wait for the government to save them. They saved themselves.

The cultural renaissance that followed gave the world new music, new art, new ways of seeing Black life in the city. Wattstax, the massive 1972 concert at the Los Angeles Coliseum, celebrated the community's resilience and refused to let the world forget what had happened.

Watts taught America a lesson it still refuses to learn.

The Pattern

Watts wasn't the first. Harlem in 1964. It wasn't the last. Newark and Detroit in 1967. Dozens of other cities exploded in the late 1960s, all for the same reasons: poverty, police brutality, broken promises. After King was assassinated in 1968, uprisings erupted in over 100 cities - buildings torched, stores looted, neighborhoods torn apart by grief and rage.

The government responded with force, not reform. More cops. More prisons. More surveillance. The War on Drugs turned Black neighborhoods into occupied territory. Mass incarceration exploded. Police departments militarized. The cycle continued.

King took the lessons of Watts north, launching the Chicago Campaign to fight housing discrimination and poverty. He told reporters the problems were "environmental and not racial" - economic deprivation, isolation, bad housing, despair. He pushed for programs to address the root causes.

Those programs never came. King died three years later, still fighting. In his autobiography, published posthumously, he wrote about Watts: "The looting was a form of social protest very common through the ages as a dramatic and destructive gesture of the poor toward symbols of their needs... The objective of the people with whom I talked was consistently work and dignity."

The uprising didn't change the system. It revealed it. And what Watts revealed was this: you can't promise freedom and deliver nothing but violence. You can't preach equality and enforce poverty. You can't tell people to be patient while you crush them under your boot.

Fifty years later, the same patterns repeat. The same lies. The same excuses. The same dead bodies in the streets.

Watts still hasn't recovered.

Sources

- Gerald Horne, Fire This Time: The Watts Uprising and the 1960s (University Press of Virginia, 1995)

- Josh Sides, L.A. City Limits: African American Los Angeles from the Great Depression to the Present (University of California Press, 2003)

- Governor's Commission on the Los Angeles Riots, Violence in the City: An End or a Beginning? (McCone Commission Report, 1965)

- Jerry Cohen and William S. Murphy, Burn, Baby, Burn! The Los Angeles Race Riot, August 1965 (1966)

- Martin Luther King Jr., statements and addresses, August 1965, King Institute at Stanford University

- Max Felker-Kantor, Policing Los Angeles: Race, Resistance, and the Rise of the LAPD (University of North Carolina Press, 2018)